In the late 1990s, when R&B was thriving off the visionary futurism of producers like Timbaland and The Neptunes — and continuing the big-budget electronic-soul tradition of their own formative influences, like Jimmy Jam / Terry Lewis and Teddy Riley — it would have rightly been considered retrograde to demand a return to the old model of ’60s-style live-band soul as a supposedly necessary corrective. But while the early millennium’s take on pop’s perpetual anti-nostalgia discourse occasionally made attempts to damn unsynthesized Stax/Atlantic-style roots-funk as an example of reactionary purism, the truth (and soul) of the matter was far different.

The soul revival that hit its stride starting in the early 2000s wasn’t some kind of revisionist retro-nemia. In many cases, it was a long-overdue acknowledgement that there were people still not only interested but more than capable of playing the kind of music that a feverish reissue market and a generation of cratediggers had whetted appetites for. You can spend only so much time listening to the kind of funk and soul-derived beats that made the golden age of hip-hop so pivotal before happily succumbing to the curiosity of where those staggering horn charts and head-nod drum breaks all came from — and where you can get more. After all, if this was the kind of music that gave RZA and Kanye and Dilla such revelations, it would have to be more than worth engaging with and appreciating no matter when it came out.

While the Brooklyn of the time is remembered 20 years later as an incubator for hipster buffoonery and/or “indie sleaze” depending on how embarrassed you still are about trucker hats, it was also the biggest incubator of a soul revival movement that continues to outlast just about every other Rock Is Back trend-hop that it shared music press with. And it provided a completely different respect for analog-recording values and vintage aesthetics that had even less time for irony than it did for putting up an anti-pop bulwark. We’re talking about the kinds of musicians whose biggest creative differences tended to revolve around recording technique and chops, a version of exclusionary thinking that was driven not by backlash but by the desire to recreate something wonderful as faithfully as possible.

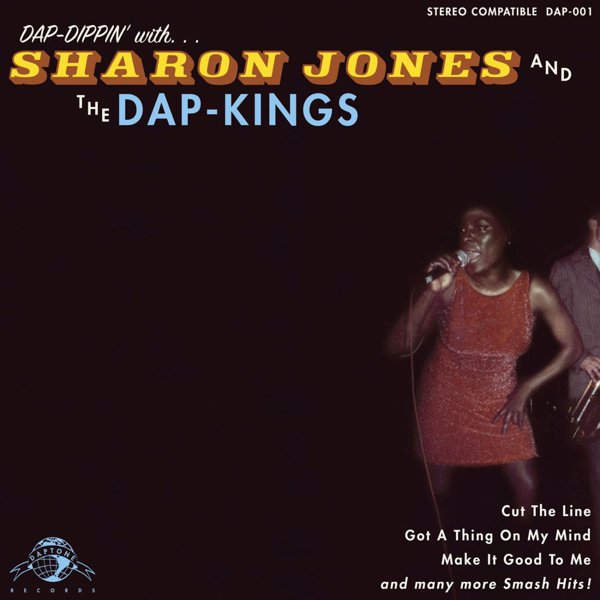

By the end of the ’90s, the cream of relatively short-lived NYC-based Desco Records — local bands like The Sugarman 3, The Mighty Imperials, and the Daktaris — was laying a foundation of young funk enthusiasts that were more than happy to add veteran singers like Lee Fields and Sharon Jones into the fold. When the 2000 split between Desco co-founders Gabriel Roth and Philippe Lehman shuttered the label, they bypassed the usual “indie vs. commercial” side of the aesthetic struggle to land on a far more primal competition based on record-collector and DJ idiosyncrasies of taste. You want to do classic soul? Well, we’re more into the heavy psychedelic-funk side of things. OK, there were money and business issues behind that disagreement, too, but it all came out in the wash: from the split emerged two still-strong specialist labels that embodied the heart of the movement.

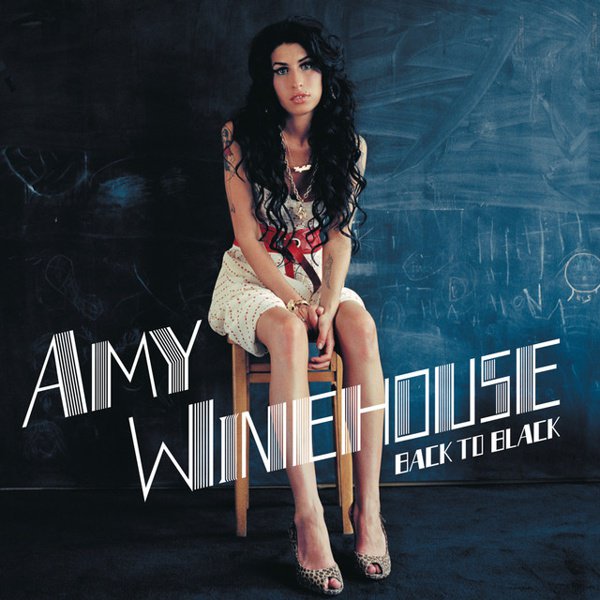

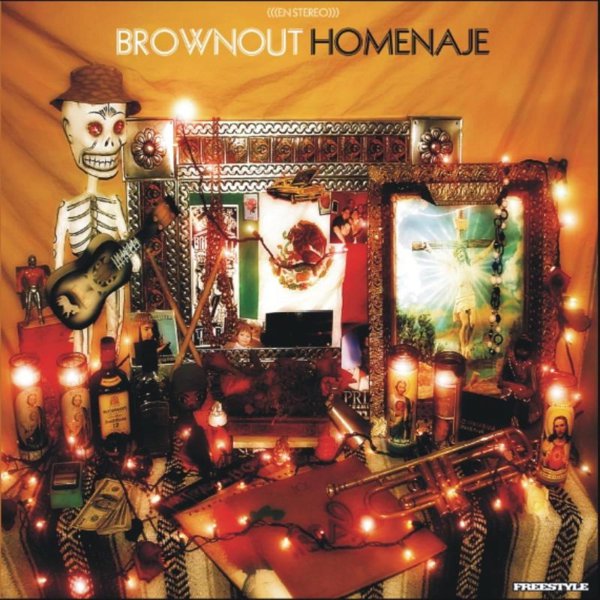

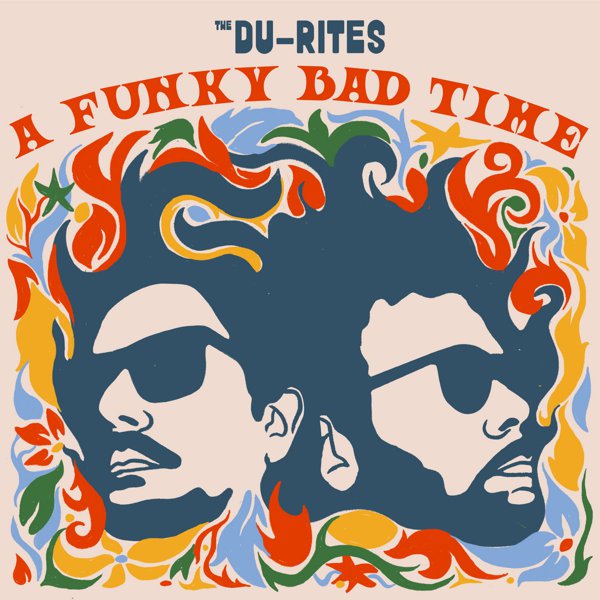

Roth’s label Daptone Records became the hottest brand in soul revival, with the Dap-Kings — the band he led under the alias Bosco Mann, first brought to prominence by their stunning albums with Sharon Jones — quickly becoming a go-to group of players to the stars, whether those stars were Amy Winehouse or Joe Bataan. Meanwhile, Lehman would motivate a succession of labels, continued by producer/bandleader Leon Michels — Soul Fire, Truth & Soul, Big Crown Records — that emphasized the grimy, lo-fi-but-highly-skilled corner of funk that was tailor-made for people who got into the music through Wu-Tang Clan. And no hard feelings either way: the crossover between the artists on these two labels overcame any narcissism of small differences to embody a broader range of soul and funk influence — Latin boogaloo, Ethio-jazz, Nigerian Afrobeat — that highlighted just what an international language this music really was.

But if the soul revival movement didn’t necessarily start there — you could find like-minded revivalists on the West Coast, in Europe, basically anywhere a group of heads got their minds blown in ’91 by the James Brown Star Time box set or DJ Shadow and Cut Chemist’s soul 7”-collection mixes — it definitely didn’t stop there, either. This list is far from exhaustive, and generally focuses on the emerging artists who became known via the scene, rather than the icons like Dr. John or pop stars like Bruno Mars that they’d eventually collaborate with. But that just means this isn’t just music that people brought back on a whim or to be trendy — it’s just a reminder that, even in a world with no shortage of amazing pop futurists, the sounds of what people generally consider “the past” are still capable of blowing your mind in the here and now.