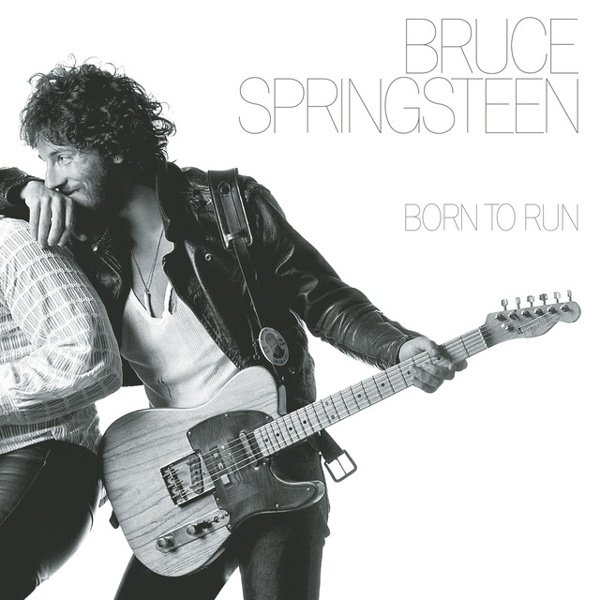

Recommended by

Born to Run

Just about everything you need to know about Bruce Springsteen can be found in the opening lines on the title track of the album that made him a superstar: that juxtaposition of a runaway American dream and the slant-rhyming counterpoint of suicide machines, emphasizing that sense of illusory postwar freedom feeling fraught with an uncertain gaze into tomorrow’s oblivion. Born to Run is where the protagonists of Springsteen’s songs start really feeling the pressure, and not just from the epochal desperation of the well-worn yet eternally-powerful title cut, or the mission-statement opener “Thunder Road” and its symbiotic relationship between feeling trapped (“I just can’t face myself alone again”) and trying to live with an increasingly narrow set of options to escape (“we got one last chance to make it real”). It runs deep in the last-ditch criminal make-good struggle of noir-jazz ballad “Meeting Across the River,” the way the deceptively upbeat “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” turns the E Street Band’s origin story into an escape route from existential isolation, and the sadness of a faded (and gender-ambiguous, possibly more-than-)friendship in “Backstreets.” Even the most romantic number, “She’s the One,” is riddled with warnings and self-doubt over being taken for a sucker by someone he desires because he needs that love to save him from the bitterness. And the stoplight drag-race energy of “Night” can’t fixate on how freeing a fast drive can feel without the juxtaposition of a mundane grind of an existence that no amount of tire smoke can ever obscure. But then, with a breath-snatching finality, closer “Jungleland” inverts the dynamic of its predecessor album, stepping back from the stress and the anxiety to see a bigger, less world-weary glimpse of rebellious glory. As a rock record goes, Born to Run sounds like two tons of dynamite, a version of 1975 that could echo endlessly in either chronological direction from Bo Diddley to the Hold Steady. A bigger budget than Springsteen’s first two albums helped, as did the band leaning full-tilt into a broader-than-Broadway theatricality that only Jim Steinman dared to try and top. But it was even more crucial that this was rock that maintained a deep connection to R&B even as radio formats and genrebound pigeonholes did their best to sever them; if Otis Redding had lived to this point you could picture him doing a perfect spirit-of-Stax “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” over the exact same backing track. So yeah, this album was breathlessly hyped and moved more units than the Ford Mustang, an instant-canon work so resonant with the public that even the Muppets of Sesame Street had to riff off it. But Born to Run knew what was on the looming late 20th Century horizon: this is music that operates under the slow-dawning realization that the working-class factory-floor youth of the ’70s would wind up pioneering the concept of being less successful than their parents, and the American dream was running away faster than any muscle car could catch up to.