Recommended by

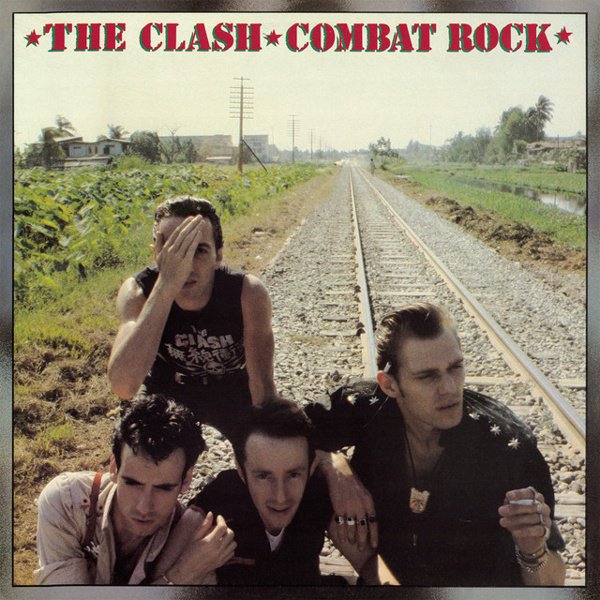

Combat Rock

Sandinista! saw the Clash trying to divine the future of music as it existed outside the Western world of guitar rock, but their decision to put out a triple LP’s worth of ideas made it feel a little too overwhelming, the kind of approach that might go down great with critics but wouldn’t do Pink Floyd numbers in record stores. Yet all they had to do to notch that final Big In America landmark was to distill Sandinista!‘s global pop-punk-dub-funk futurism approach into a single LP without tweaking it too much — save for a bit of radio-friendly and MTV-ready polish here and there, maybe. What came out of that idea was the album that broke the band in both senses of the word. The commercial gleam of hits like the jittery garage-R&B hybrid “Should I Stay or Should I Go” and the new wavey dance jam “Rock the Casbah” bothered diehards, but those would be the least of their worries: the sessions had been marred not just by Topper Headon’s narcotics struggles, but by the massive creative and personal rift that had started to sabotage the Joe Strummer-Mick Jones songwriting partnership. All those compromises, all those struggles, all the inevitability of the band’s collapse — and Combat Rock still comes out sounding more fascinating than flawed, one of those records that spurs a million what if questions around how things could’ve played out if they’d just kept their shit together. While the hits were some of the catchiest songs they’d ever done, the deep cuts confront their stylistic sprawl, a band recognizing they were being world-music magpies and trying to reassert their own inside-looking-outwards perspective into something they can rightly claim as their own. So when they hit the dancefloor they split the rubber-and-aluminum difference between b-boy fluidity and no-wave jaggedness (“Overpowered by Funk”), their updated vision of ’50s rockabilly is charged with a sardonic lefty politics that would’ve put them on the HUAC blacklist (“Know Your Rights”), and when they sink into dub they wind up channelling Scorsese (“Red Angel Dragnet”) and the Beats (Allen Ginsberg-featuring “Ghetto Defendant”) as much as they do Lee Perry and King Tubby. It’s all run through with the pervasive subcultural anxiety that the immediate future would be dominated by late-Cold War hostility and sociocultural struggle, and it peaks with their last great song, the achingly sorrowful “Straight to Hell,” one of rock’s most bitterly empathetic portraits of classist and racist indignity. Combat Rock‘s victories all feel pyrrhic — a band on its last legs belting out one last attempt to push back against a world that the Reagan-Thatcher axis had knocked towards the right — but in the end, their burnout still provided a strong source of heat.