Recommended by

Frequencies

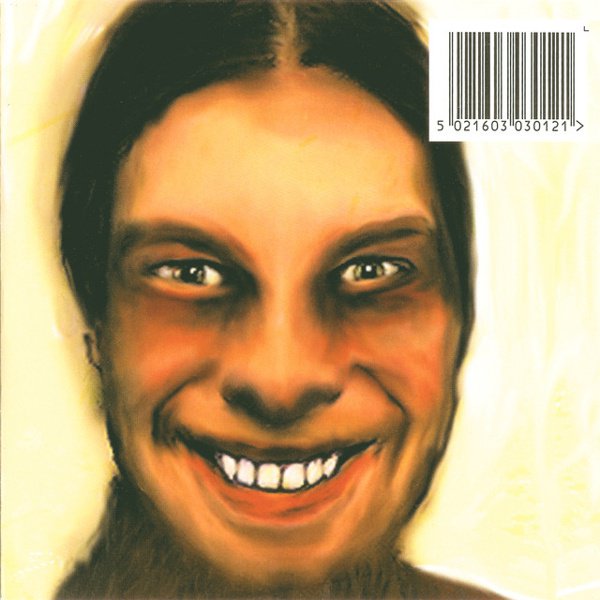

How to understand something as important as LFO’s 1991 album, Frequencies? Originators—the ones who get there so early you can’t call them early adopters, as there’s nothing to adopt—have to grind to make anything happen at all. The pioneers have nothing to consult but a handful of things that already exist. Gez Varley and Mark Bell, rival breakdancers in Leeds, met in 1988 and formed LFO. “Techno was an extension of hip-hop,” Varley said in a 2019 interview, which explains some of it. The records that inspired them were not anything you’d call techno: “King Kut” by Word of Mouth with DJ Cheese, Schoolly D’s “P.S.K.,” Pink Floyd’s “On The Run,” Rhythim Is Rhythim’s “It Is What It Is,” and The Unknown DJ & 3D’s “Beatronic.” They teamed up with a local DJ named Martin to make their first single, “LFO.” Cassettes of the track were played out at raves in and around Leeds and Sheffield. (Williams only stuck around for this song, the group’s only real hit.) Rob Gordon got the LFO demo and brought it to the other two-thirds of Warp, Rob Mitchell and Steve Beckett. LFO was one of the first signings to Warp and Frequencies was the label’s first big album (and their first album, period). Varley and Bell used the Roland 303 and Roland 808 and a Casio CZ-1 (and a few more bits) to make this weird new electronic music that had no name. Frequencies sounds intermittently like Kraftwerk, but it’s too loose and scrappy to be mistaken for anything that came before. You can hear whispers of hip-hop and house, in a rhythmic move here and a brief sample there. “Intro” lays out a sort of manifesto, read by a voice going through an effect. After trying to define house, the voice goes on to shout out “the pioneers of the hypnotic groove—Brian Eno, Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk, Depeche Mode, and the Yellow Magic Orchestra.” That helps a little. The rave ethos is in there, too: “We hope our music will bring everyone a little closer together. Gay, straight, black or white. One nation under a groove.” Hard to imagine anyone being that sincere now. This is rudimentary stuff, nothing too lush or complex. It just goes, and it sounds like what it was—two nineteen-year-olds playing with relatively new gear in an entirely new setting, with nobody to worry about but a few folks dancing in abandoned warehouses.