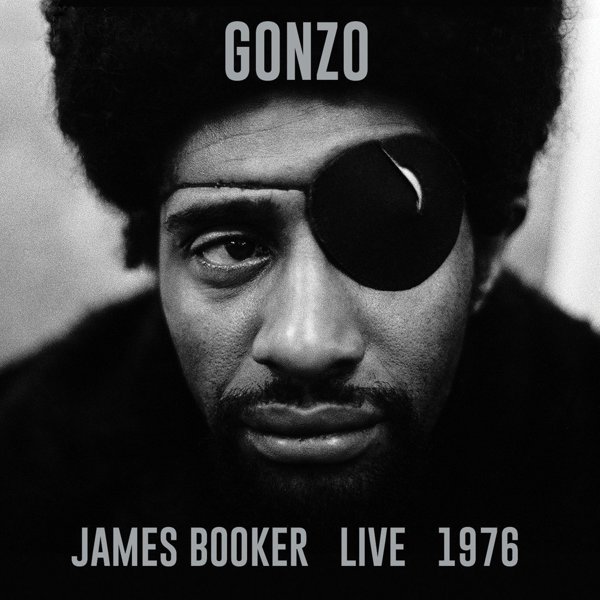

Gonzo - Live 1976

If Allen Toussaint was the world-shaping musical figurehead of postwar New Orleans — a man with deep connections, endless reach, and a warehouse full of honors and awards — James Booker was his tragic counterpart, a pianist of unfathomable talents who bridged the gap between Ray Charles and Rachmaninoff yet died largely forgotten at 43. Booker had brushes with mainstream success in the States: releasing the solid Junco Partner on Island in 1976, touring with Dr. John and Jerry Garcia, and playing sideman to Labelle and the Doobie Brothers. But being burdened with a morphine addiction he traced back to a childhood accident, and living as a gay man in a place and time that still considered it unspeakable, meant that his prospects for stardom would always be limited, leaving him always on the edge of ostracism. Then he started touring Europe and discovered that, yes, he was a bonafide star — that, for all his struggles and turmoil, he was a man who could reflect an idealized modern America to them through his flamboyant translation of his home’s musical traditions. Aside from a few thrown-in full-band studio tracks from what sounds like the early ’60s (where Booker plays organ rather than piano), the performances on Gonzo: Live 1976 are mostly recorded solo in Germany, with some additional material from an unaccompanied ’78 BBC session. And these performances are as direct as it gets, as Booker rolls out a succession of New Orleans R&B standards (“Junco Partner”, “Tipitina”), blues and early soul classics (“Let Them Talk”; “Please Send Me Someone To Love”), and his own originals (“One Helluva Nerve”; “United Our Thing Will Stand”) that run such a versatile breadth of style and mood that it’s remarkable in itself that his voice can unite them. Not just his literal voice, of course — raw in its drawl, sometimes harsh, but with the kind of gut-punch emotion that dares to approach Nina Simone levels — but the one he’s expressed through his fingers. It’s his elaborate, unpredictable yet almost instinctively right extrapolations of rhythm & blues into the outermost realms of both improvisational and compositional music, and it works because Booker still knows where the groove is deepest — it’s almost easy to forget that there isn’t even a rhythm section at work here. Toussaint himself recognized these qualities in Booker — the rest of the world should, too.