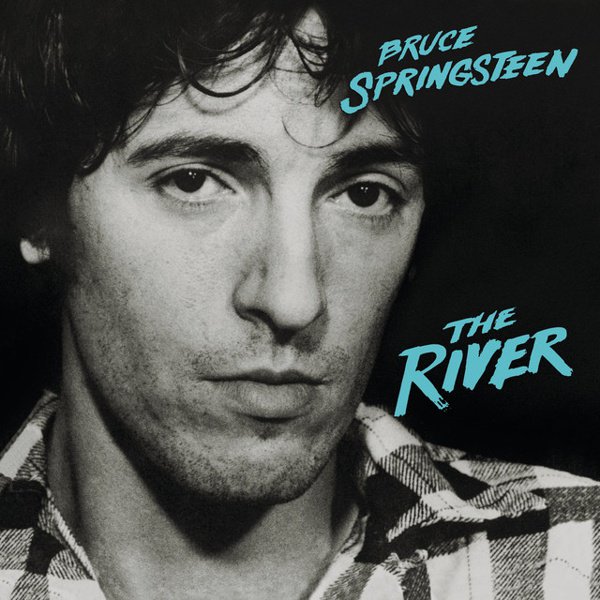

The River

It took nearly three full years and a big power struggle between Springsteen and his manager for Darkness on the Edge of Town to follow up on the breakthrough of Born to Run, so it’s a bit funny in retrospect that the double LP that followed was considered nearly as big an ordeal to make. But it really was a lot: Springsteen had started off planning a new album, The Ties That Bind, by building around several circa-’77 songs left over from the Darkness sessions, but eventually grew dissatisfied with the idea of putting together an album that felt half-familiar already and didn’t have some greater conceptual sweep or overarching narrative. So in the wake of Tusk and The Wall and London Calling, Bruce decided to take a shot at putting his own stamp on the idea of the Blockbuster Double LP Statement. And considering what followed, The River feels like a necessary but conclusive burst of energy centered around the signature identity he and his band worked every last angle of, a culmination that arrived to close out the first act of his career just in time to prevent it all from sounding spent. And that four-sided sprawl let him work out every last contradiction and mood-shift his discography had been building to reconcile. The ’77 cuts have power to spare, of course; the once-prospective title cut that remains stationed as the first of twenty tracks still works as an overarching setup for an album that strains from the push and pull between jaded, lonely defeatism and familial, communal warmth. Itt’s worth noting that those same sessions gave us both the affectionately snotty mother-in-not-yet-law gripe “Sherry Darling” and the devastating, more-sorrowful-than-bitter post-breakup reckoning “Point Blank,” both of which examine how financial hardship can feel inextricable from emotional poverty. And those tangled-up feelings blur all the lines between hope and the reasons you need to hold out hope, especially when they’re fleshed out by the songs he cut after he went back to the drawing board. The big hit, “Hungry Heart,” used a deceptively cheerful Spector-oid arrangement to embody the regrets of a man who impulsively abandoned his family, the upbeat-sounding gearhead rocker “Cadillac Ranch” actually envisions the titular car as a hearse and the afterlife as a junkyard, and “Crush On You” is another strong entry in Springsteen’s pantheon of love-as-desperation studies — lighthearted, sure, but still aware of how rash it can be for a “little stranger standing ‘cross the room” to somehow start feeling like “a walking, talking reason to live.” Meanwhile, more of his songs than ever draw off an emotional directness that supersedes his more elaborate lyrical tendencies; “Out in the Street” and “Fade Away” are a long distance from the elaborate fine-detail storytelling of Born to Run, but sound every bit as euphoric and wounded respectively as his best earlier material. That’s thanks not just to Springsteen’s sincerely affecting vocals, but his band’s incredible breadth as the greatest American roots-rock outfit since CCR. That impact peaks halfway through with The River’s title cut — a gut-punch ballad of struggling young married life, drawn from his own sister’s experience with her laid-off husband through America’s protracted deindustrialization era. But the album’s denouement is just as harrowing, from the journeys to unsatisfying destinations alluded to in “The Price You Pay,” through the acute protective devotion of “Drive All Night,” down to the horror-witnessing, insomnia-causing ways a stranger’s death can still haunt you on “Wreck on the Highway.”