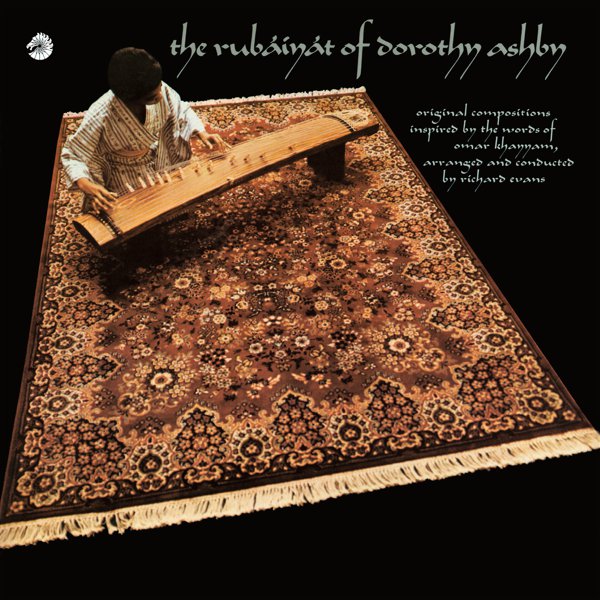

The Rubáiyát of Dorothy Ashby

The same year that Alice Coltrane hit her stride in reinventing free jazz as a vehicle for spiritual East-meets-West transcendence, her still-underheralded predecessor in the rarefied world of jazz harp was also making a move towards Asian musical influences — just to much different ends. The Rubaiyat of Dorothy Ashby, a concept record based around the poetry and philosophy of Omar Khayyam, was the end of a brief but stunning soul-jazz run on Cadet under the arrangement of Richard Evans, as well as her last as a bandleader before spending most of the ’70s playing sessions for the likes of Stevie Wonder and Bobbi Humphrey. And you can hear why she’d fit in so well on those ambitious artists’ works: in expanding her repertoire to incorporate both the Japanese koto and her own glimmering, operatic voice (the latter turned into a stunning multi-tracked chorus of judgement-casting angels on “The Moving Finger”), she finds a welcoming depth in the commonalities that come from trans-continental hybridization. Maybe it’s as straightforward as hinging it all around a backbone of opulent arrangements that blur funkiness and elegance — right up there with anything Charles Stepney concocted for Ashby’s labelmates — but there’s also a strength in making what was once considered “exotica” feel like integral aspects of cusp-of-the-’70s soul, from the way that “Wax and Wane” juxtaposes African kalimba and percussion with flutes and vibraphones to the way “Dust” transmutes post-bossa rhythms into an epiphany disguised as a reverie. And Ashby’s technique makes her once-novel choice of instrument feel self-evident, contemplative in her crystalline glissandos and startling in her emphatic, sharp-noted accents.