The history of Western music is a long series of actions and reactions: a particular style of music becomes popular in a large community and remains in the mainstream for a period of time, until musicians and listeners start to grow tired of it and begin producing and consuming music that rejects the conventions of the previous style and reacts against them, resulting in a new form that – if pleasing enough to both musicians and listeners – then becomes a new convention.

The emergence of bebop is a perfect example of this dynamic. In the 1930s, jazz had become mainstream popular music in the United States, and was typically played by large ensembles to accompany dancing. The music required significant skill to play but was not usually challenging for the listener; the sound of swinging, big-band jazz was lush and pretty and fun and appealed easily to a mass audience.

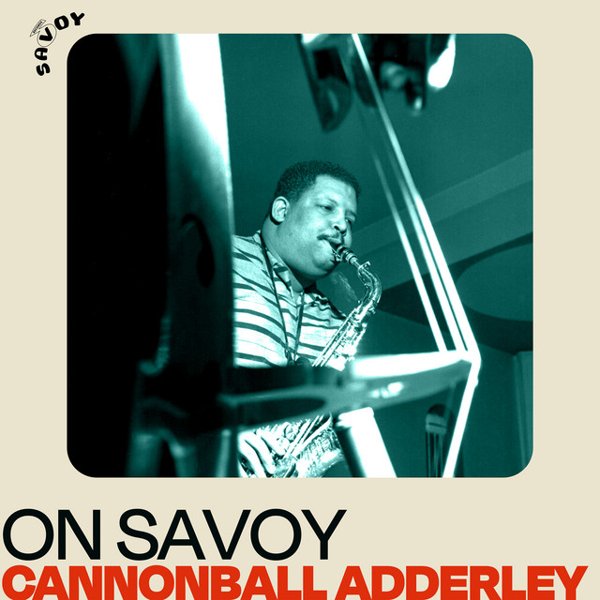

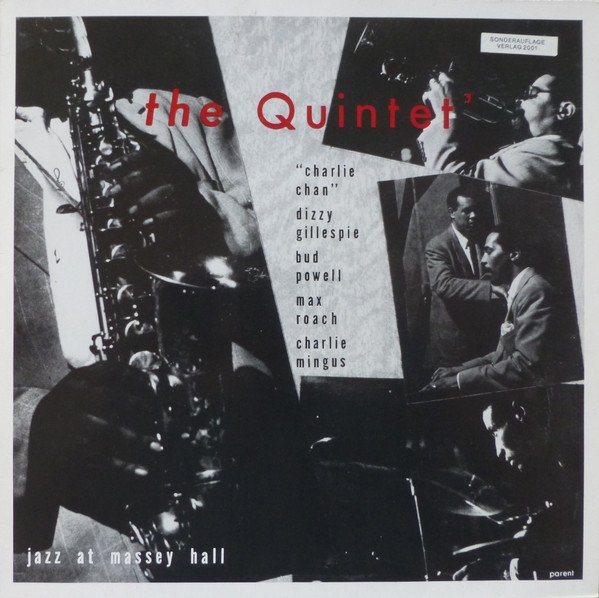

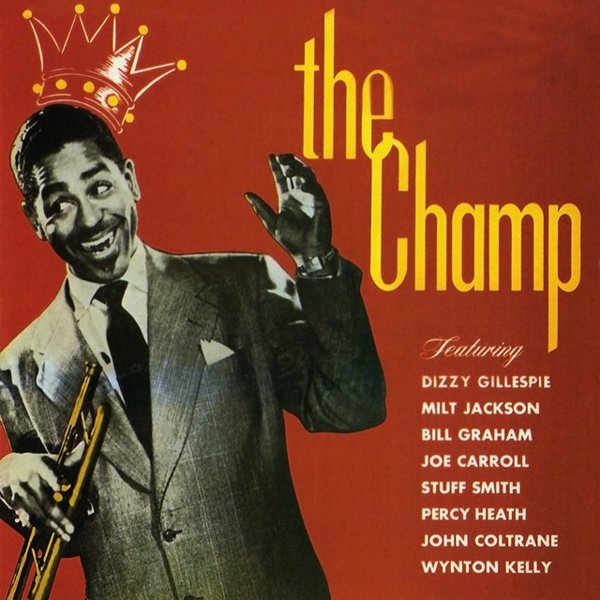

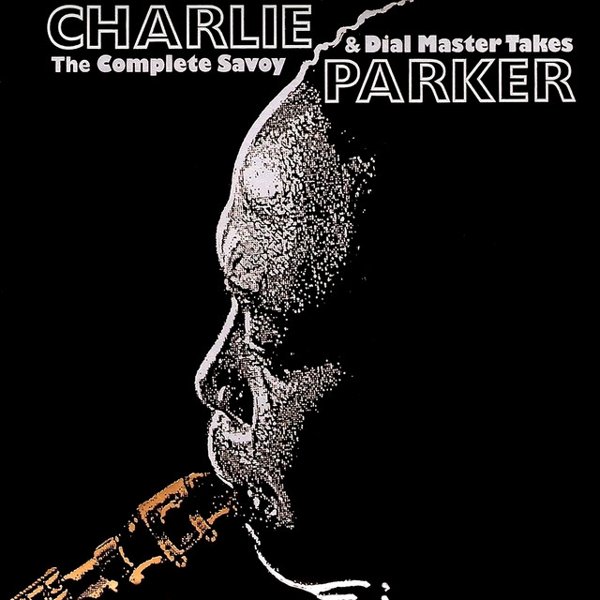

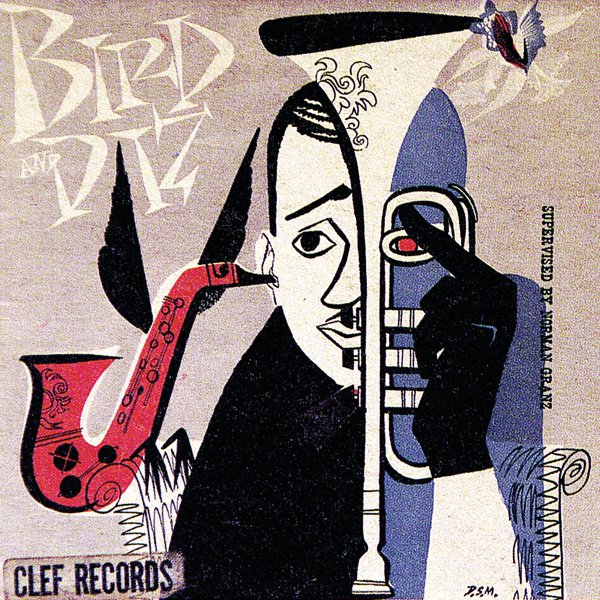

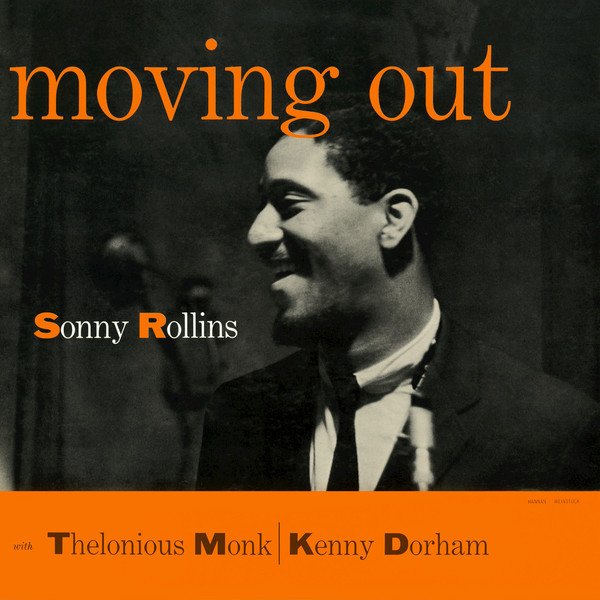

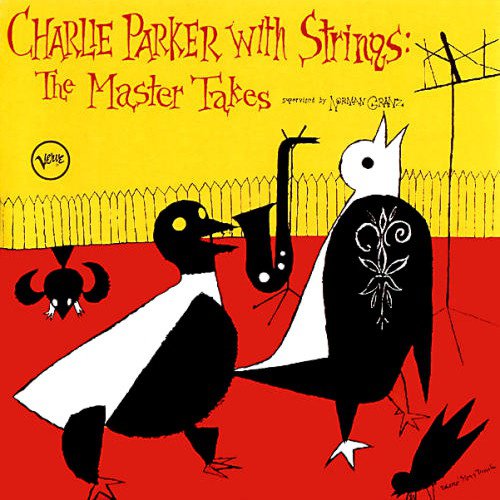

By the early 1940s, however, a coterie of New York musicians were growing tired of big band swing’s conventions and were experimenting with a new approach to jazz that involved headlong tempos, complex melodies, and extended chromatic chords. The nucleus of this group was saxophonist and composer Charlie Parker, a once-in-a-generation talent whose addictions led to a tragically young death; others in the circle included trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis (the latter of whom would go on to be a central figure in the emergence of “cool” jazz a decade later), the highly idiosyncratic pianist Thelonious Monk, drummer Kenny Clarke, guitarist Charlie Christian, and bassist Charles Mingus.

Bebop ensembles were small, and the new tunes in this style were often based on the chord progressions of swing standards – for example, Charlie Parker’s iconic “Ornithology” was a new melody written on the chord changes to “How High the Moon” and played at a breakneck tempo. Bebop was not for dancing to, but for listening to, and it seemed to be written more with musicians in mind than for the general public; it was music by virtuosos, for virtuosos. Nevertheless, it found a large audience among established jazz fans and quickly became the new conventional form; for the next several decades, even as the action-reaction process continued and bebop lost ground to the “cool” movement, hard bop, soul jazz, and rock-jazz fusion, jazz would continue to be primarily a concert music performed for listeners in clubs and concert halls rather than for dancers.