The Black Artists Group (BAG), formed in St. Louis, Missouri in 1968, is often seen as a junior stepsibling to Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), which launched a few years earlier. But while the AACM was focused entirely on music, BAG was a multidisciplinary arts organization that included writers and poets, dancers, actors and painters. Because of this, many BAG performances featured elements of all of these in combination, and albums often combined jazz with poetry and theater. One of the albums released by a BAG collective, Children Of The Sun’s Ofamfa, featured the statement “The dancers who worked with the group are Carolyn Zachary, Etta Jackson, Johadi, and Sandra Weaver” on the back cover.

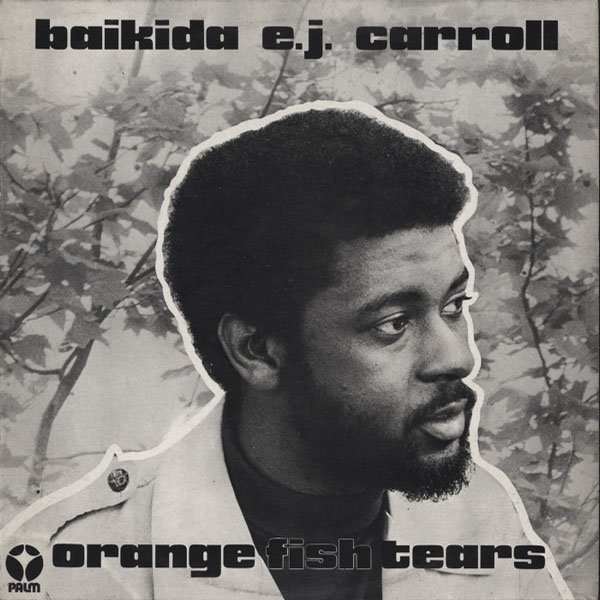

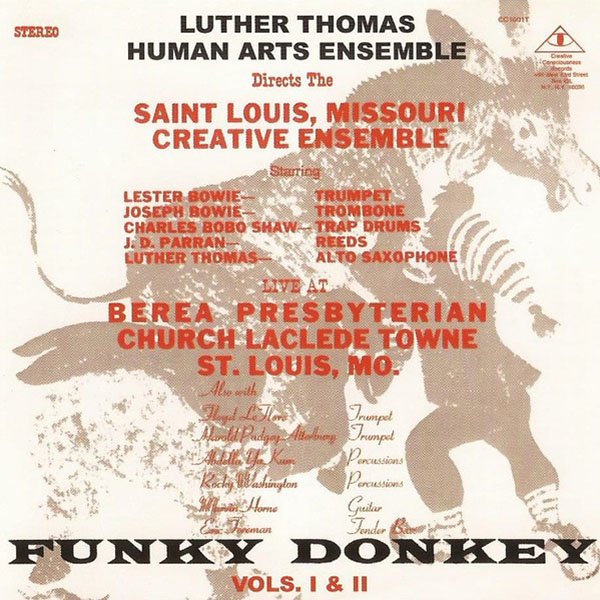

The core musical members of the group included saxophonists Julius Hemphill, Oliver Lake, J.D. Parran, Hamiet Bluiett, and Luther Thomas; trumpeters Baikida Carroll and Floyd LeFlore; trombonist Joseph Bowie; and drummer Charles “Bobo” Shaw. Trumpeter Lester Bowie, Joseph Bowie’s older brother, was also affiliated with BAG, though he was primarily a member of the AACM and its best-known group, the Art Ensemble of Chicago. A key early event that encapsulated the general attitude toward multi-disciplinary art was a summer 1968 performance of Jean Genet’s play The Blacks that included dancers and live music onstage. Not long afterward, the group incorporated with the state of Missouri as a not-for-profit organization.

BAG and the AACM were just two of a slew of cultural organizations affiliated with the broader Black Arts movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and they benefited from connections with predecessors like dancer, choreographer and anthropologist Katherine Dunham, whose St. Louis-based Performing Arts Training Center (PATC) brought Julius Hemphill in to teach a music program as part of a broader curriculum that included philosophy, history, social sciences and the humanities. Dunham (who split her time between Senegal, Haiti, and East St. Louis) also exhibited artifacts she had gathered in her travels in a small museum.

Federal grants for a Model City program in St. Louis (a mirror of one in Los Angeles’s Watts neighborhood) and artist-in-residence efforts kicked BAG off in earnest; Hemphill and writer Malinké Elliott were the administrators of the funds and recruited their BAG peers and other artists to take advantage of the opportunities available, and things quickly blossomed. They took over an abandoned warehouse as a headquarters, paying $1 a year in rent, and all pitched in to restore the building and make it into a multi-function space that allowed for music, dance, and theater classes and rehearsals.

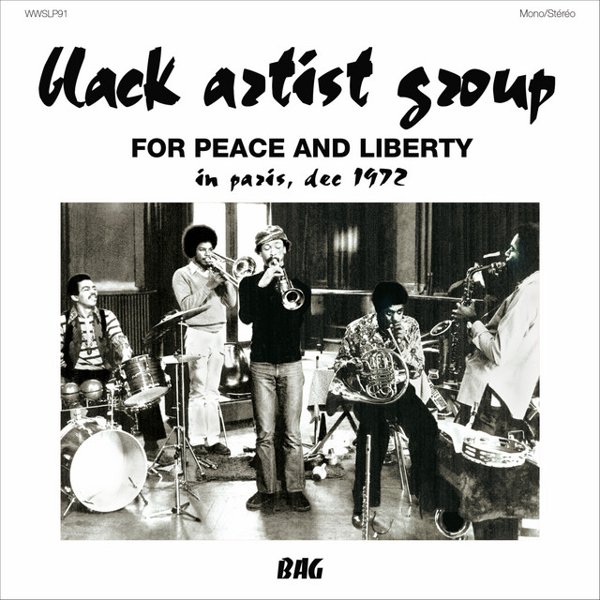

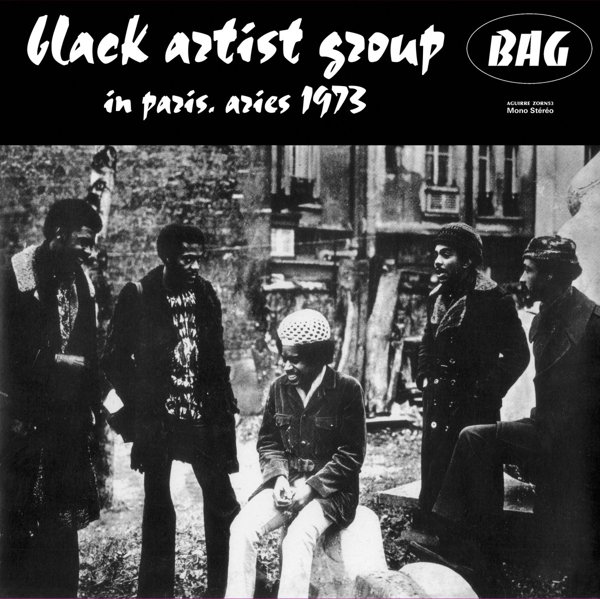

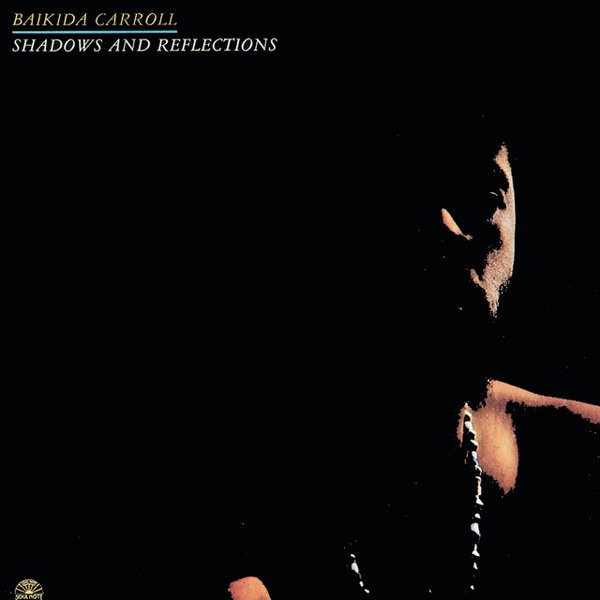

Throughout 1969 and 1970, BAG was a vital part of St. Louis’ artistic community, though often controversial — their writers and poets found voice in local alternative and underground papers, but the militant plays they put on often shocked and angered as many people as they thrilled, and free jazz, of course, has always been and will always be an acquired musical taste. By 1971, the organization was already beginning to run out of funding and spin apart, as the various members found ways to make things happen on their own. Both Hemphill and Lake recorded their first albums — Dogon A.D. and Ntu: Point From Which Creation Begins — independently, as did the umbrella groups Children Of The Sun and the Human Arts Ensemble. In late 1972, a group of BAG musicians (Lake, Carroll, Joseph Bowie, and Shaw) went off to France, where they performed and recorded. One album, In Paris, Aries 1973, was released at the time, while another, For Peace And Liberty (In Paris, December 1972) didn’t emerge until 50 years later.

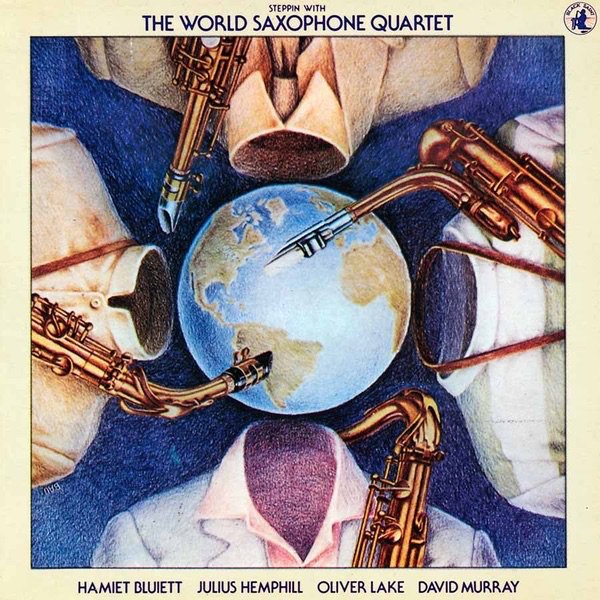

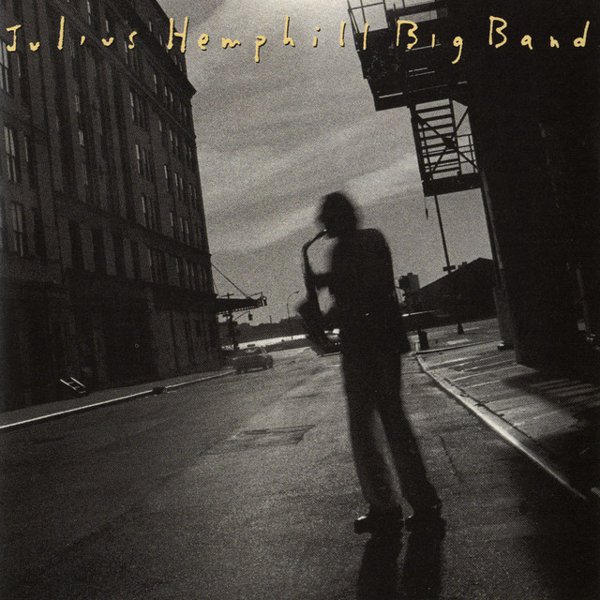

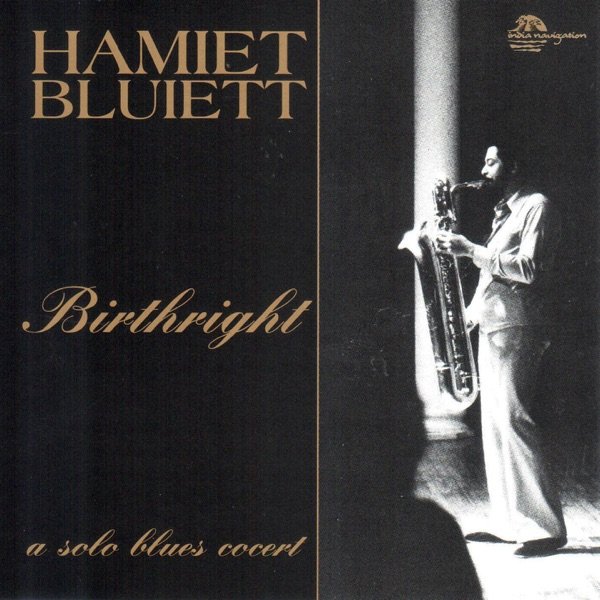

BAG officially disbanded in 1972, but its members continued to work together, and established themselves as leaders, mostly in New York. Hemphill became a key figure in the Seventies loft jazz scene, and made vital and influential work until his death in 1995. Oliver Lake has had an equally important career, recording dozens of albums as a leader or co-leader and receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1993. He, Hemphill, and Hamiet Bluiett co-founded the World Saxophone Quartet with David Murray in 1977, which remained active (with various membership changes) until 2016. Joseph Bowie founded the art-funk band Defunkt, which continues to this day, and Hamiet Bluiett (who died in 2018), Charles “Bobo” Shaw (who died in 2017), and Baikida Carroll all recorded as leaders.