In 2024, American composer Morton Feldman’s position as one of the most important composers of the twentieth century seems pretty much assured. This was far from a given outcome, even thirty years prior. It probably had a lot to do with the curious presence of his compositions, which tended towards the elusive, the slow, the lengthy, and the quiet. Not for Feldman the bombast of quasi-experimental modern classical, nor the rigidities of serialist composition. Here was a composer of eloquence who spoke, through his music, with great subtlety, even as, in real life, he was gregarious, at times overbearing, problematic, and by many accounts, quite the raconteur.

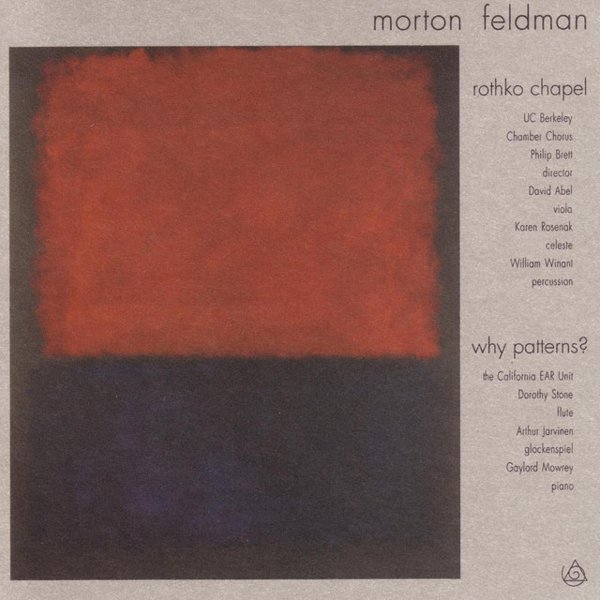

Feldman was born on January 12, 1926, in Woodside, Queens, New York City. He studied piano with Madame Vera Press as a child, and composition with Wallingford Riegger and Stefan Wolpe. His early compositions have a slightness about them that doesn’t really hint at the way Feldman’s work would develop over the subsequent decades, but a chance meeting with John Cage, who took Feldman under his wing, would prove central to his musical development. Through Cage, he also met artists like Robert Rauschenberg, and visual art would become significant to Feldman’s thinking, and critical writing, particularly the abstract expressionists: Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and his favourite, Philip Guston.

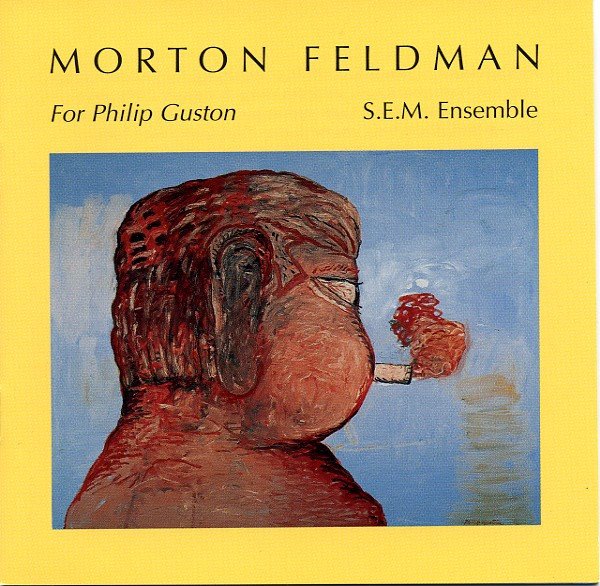

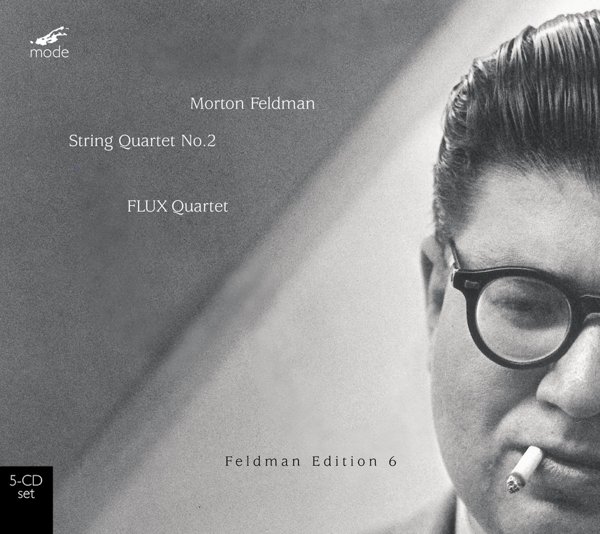

Indeed, it was through visual art, and his later love of hand-woven rugs, that Feldman found some of the important inspirations for his compositional approach, particularly their interest in scale, and in slight variation within repetition. He was also a brilliant, idiosyncratic art critic, something he is still yet to be fully recognised for; his art criticism also offered an open door to his thinking on music (both his own music, and that of other composers). While we might want to think that visual art was important to his earlier graphic notation systems, it seemed far more significant to his works of scale, such as the four-hour For Philip Guston, and the six-hour String Quartet II.

There are a few things people often say about Feldman’s compositions. One is that they are very quiet. It is hard to deny this, given his fondness for the ppppp, or pianississississimo, indication on his scores. But this seems to me to be about a redirection of attention, as well, to listen carefully and intently. It also works at a level of intimacy, and Feldman’s move toward longer pieces in his later compositions seems to shadow this as well, with Feldman wanting to give the listener a chance to develop a closer, more one-to-one relationship with the work. He was also fond, in later works, of repetition with slight variation, which accounts for these compositions’ mesmeric qualities.

And yet, there’s a tension that exists in all Feldman’s work; it can never be relegated to background. I often wonder at how exhausting, in a good way, it can be to listen to Feldman, in that you’re bound to the experience, and there’s no diverting one’s attention (and listening closely feels so much more draining than watching closely). They seem to re-train your ears, and to keep you looking out for change of incredibly subtle increment. Their power lies, I think, not in their quietness, nor their length, but in their sturdiness, the way they build a universe in a stipple, or a brushstroke. By the time of For Samuel Beckett, his final composition, written several months before he died, on September 3, 1987, of pancreatic cancer, his work had become completely sui generis.