On some slow news day in August of 2018, American news outlets began reporting that Deutsche Bahn, the German national train authority, was planning to pipe “atonal music” through the speakers of a Berlin train station to drive out the homeless. The new-music community, immediately up in arms, organized a protest concert outside the station, and the plan was scrapped. It’s a familiar story; atonal music, since its earliest incarnations, has simultaneously raised hackles, cleared rooms, and been earnestly championed.

“Atonal” or “post-tonal” music is music without a major or minor key. While it is difficult to explain that in simple terms, the sound of atonal music is often instantly recognizable, characterized by a feeling of being unmoored and irresolute at every turn. There is a lot of music-theory explaining in the atonal-music world; those who approach it often find themselves barraged with information about tone rows and retrograde inversions and the “emancipation of the dissonance.” But post-tonal musical language, intellectually fearsome though some of it is, has an abundance of simple aesthetic experiences to offer. It can be music that works on its audience, music that does not necessarily have some technical prerequisite to be understood, and music that is startlingly diverse in its aims, origins, outcomes, and feelings.

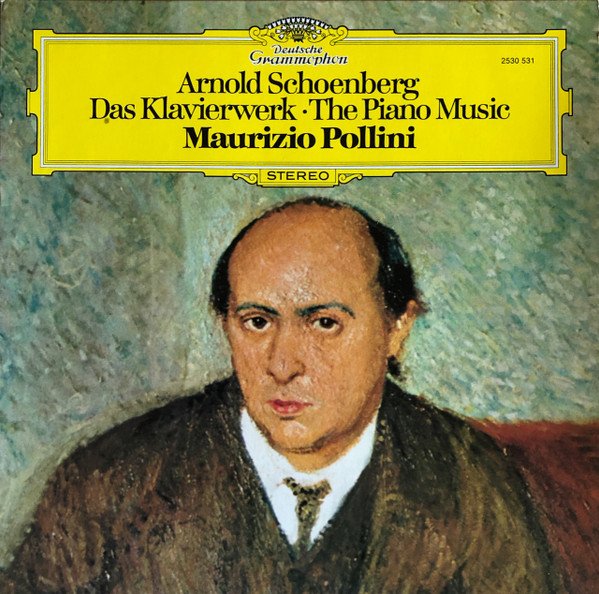

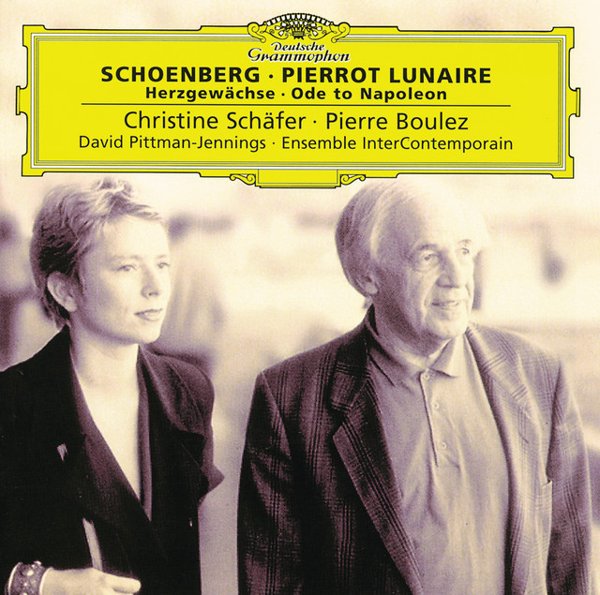

Histories vary, but the origins of post-tonality are usually linked with the Viennese composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951). With a strong case of the anxiety of influence, Schoenberg came to feel that the only way that he could build on the work of his mighty, experimental elders Richard Wagner and Gustav Mahler was to dispense with keys, which he did for the first time around 1907. While all of this began as a local matter among Austro-German composers and was not popular at first, Schoenberg’s style eventually became one of the key tributaries of Western-art-music style in the 20th century. His work and its influence are one of the reasons why dissonance of varying kinds became an inescapable presence and a hotbed of creativity in 20th-century music, from the elite salon to the Hollywood blockbuster.

The spread of atonality began because of Schoenberg’s cleverness, boldness, and good historical timing; it found champions because for some, it was the supreme expression of the apocalyptic mood of the 20th century. Theodor Adorno, atonality’s most famous advocate, argued that this adversarial type of music was the only kind that resisted the crushing pressures of capitalism – in other words, in a world where there are no longer any happy endings, pieces of music cannot continue to resolve on major chords. This mentality, shared by many composers, is one of the reasons why atonal music is often so stern, rigorous, and intellectual.

But from the beginning, atonality was also about feeling, about difficult, unresolved, illogical emotions. Schoenberg wrote, “Man has many feelings, thousands at a time, […] This multicolored, polymorphic, illogical nature of our feelings, and their associations, a rush of blood, reactions in our senses, in our nerves; I must have this in my music.” This list of albums focuses less on the technical and intellectual features of post-tonal technique and more on an exploration of the feelings that it infused into the music of the 20th and 21st centuries.

![There Will Be Blood [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5180820524367872_600.jpg)

![Harakiri [Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/Harakiri--Soundtrack-_600.jpg)

![On the Waterfront [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/On-the-Waterfront--Original-Soundtrack-_600.jpg)

![Images [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/Images--Original-Soundtrack-_600.jpg)

![Taxi Driver [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5730059667111936_v1_600.jpg)

![Lo Straniero [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/Lo-Straniero--Original-Soundtrack-_600.jpg)