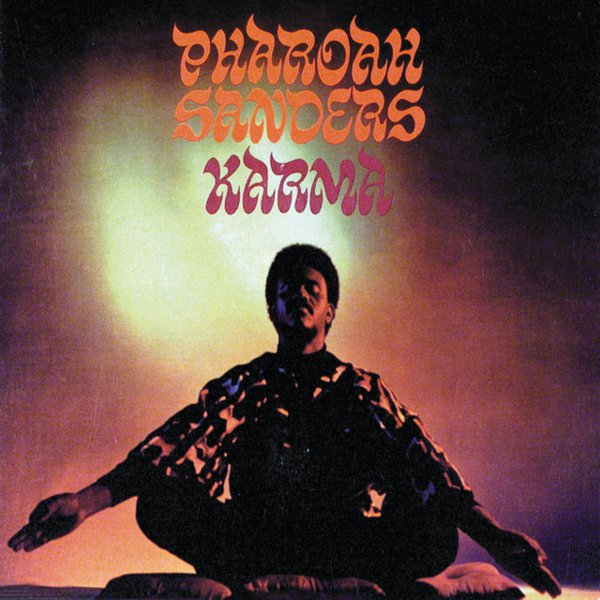

Free jazz is an umbrella term for an artistic movement that covers a broad range of sounds and approaches. It encompasses the speedy, high-energy compositions of Ornette Coleman, which let the players wander wherever the intricate melodies took them; the gospelized wails and shrieks of Albert Ayler and Pharoah Sanders; the thunderous piano avalanches of Cecil Taylor; and much more.

The movement began in the late 1950s, when Coleman and Taylor exploded onto a scene still in thrall to bebop. The music was initially scorned as atonal, or a scam perpetrated by musicians who couldn’t really play, but before long a select audience of critics and fellow artists was swept along. By the early 1960s, more and more musicians were adopting “free” methods of playing, and a scene was beginning to coalesce. Four drummers — Rashied Ali, Andrew Cyrille, Milford Graves, and Sunny Murray — began to explore new approaches to rhythm that were untethered from 4/4 time or even timekeeping as a function; their so-called “pulse” rhythms allowed for a more organic interaction between all the instruments in an ensemble, letting the music ebb and flow. Horn players, meanwhile, incorporated techniques like overblowing and multiphonics (playing more than one note at once), shrieking and roaring through their instruments, and Taylor’s piano was somehow percussive and Romantic at once.

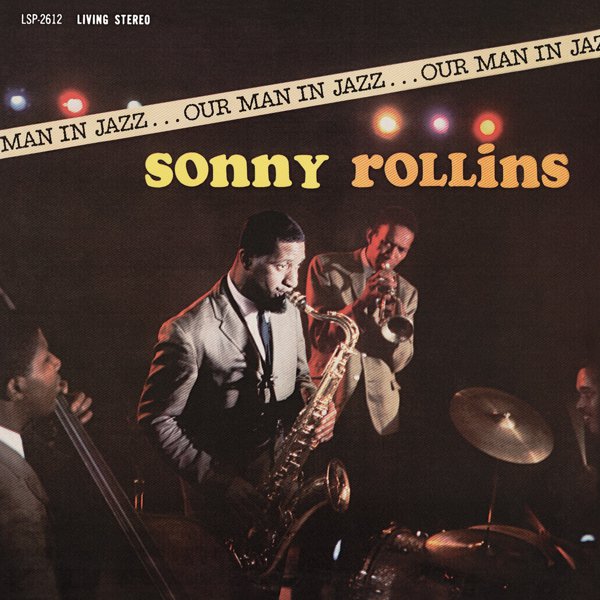

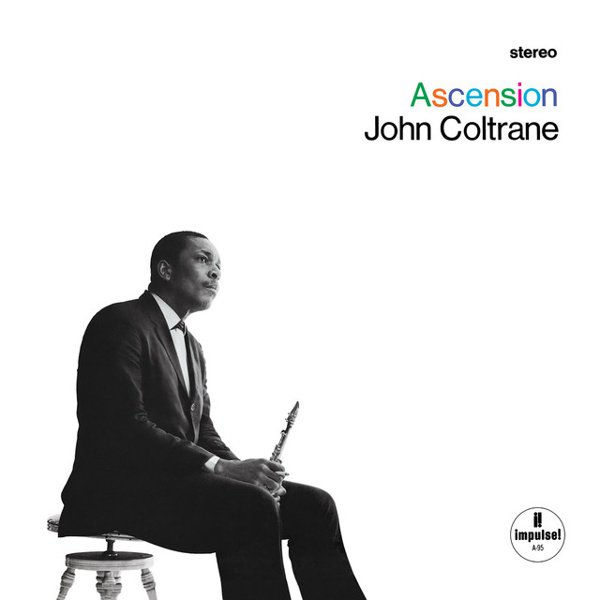

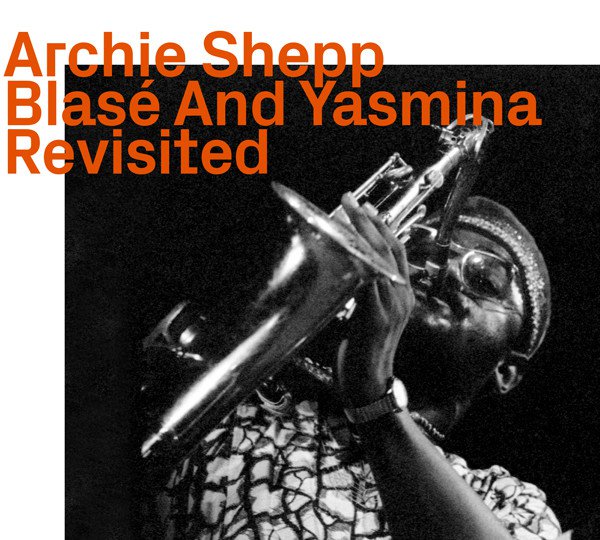

Small labels like ESP-Disk’ and artist-run imprints sprang up to document the new music, and efforts to circumvent the traditional music industry were undertaken. Artists formed short-lived guilds and collectives to get better treatment from club owners and the record industry. When John Coltrane, one of jazz’s biggest stars, began to take younger players like Ayler, Archie Shepp and Pharoah Sanders under his wing, the mainstream was forced to take notice. He got all three men signed to Impulse! Records, and used the latter two on his own sessions; Sanders joined his live band from 1965 until Coltrane’s death two years later.

Though centered in New York at first, free jazz (also known as “the New Thing”) was everywhere by the mid-1960s. In 1965, Chicago-based pianist Muhal Richard Abrams and friends formed the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), the organization that gave the world Anthony Braxton, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and many other crucial figures. In Los Angeles, pianist Horace Tapscott’s Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra embarked on its own path, creating “spiritual jazz” before anyone was using that term.

At the end of the decade, dozens of free jazz players including Shepp, Braxton, the Art Ensemble, Frank Wright, Sonny Sharrock and Don Cherry traveled to Paris for the Pan-African Festival, recording crucial albums for the BYG-Actuel label while they were in town. The Art Ensemble stayed in France for several years, releasing more than a dozen LPs between 1969 and 1971 and becoming stars in the process. By the time they returned, the scene had changed; the explosiveness of the 1960s free jazz scene was giving way to the more introspective, intellectual music of the so-called “loft jazz” era.