Though it seemed shocking at the time, jazz-rock fusion was inevitable. Despite retroactive attempts by reactionary critics to wall it off, plenty of jazz musicians had always been open to pop sounds, and when Sixties rock proved creatively fertile, opening up new compositional vistas and developing radical new production techniques, they were listening appreciatively. As early as 1966-67, jazz players like guitarist Larry Coryell and saxophonist Cannonball Adderley were incorporating rock rhythms and arrangements into their music, but fusion, or “jazz-rock,” really took off at the end of the decade, when Miles Davis brought electric keyboards and guitars into his music on albums like Miles in the Sky, Filles de Kilimanjaro, In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew. In partnership with Teo Macero, he also broke the grip of the “perfect take” once and for all, using the studio as an instrument as adroitly as any musician ever has.

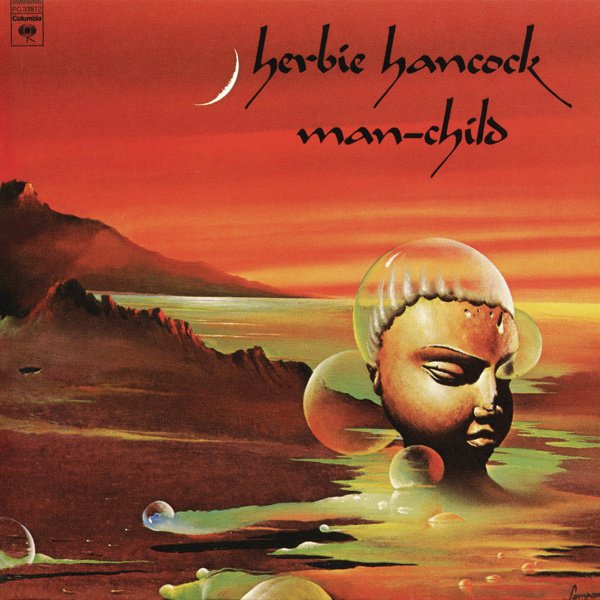

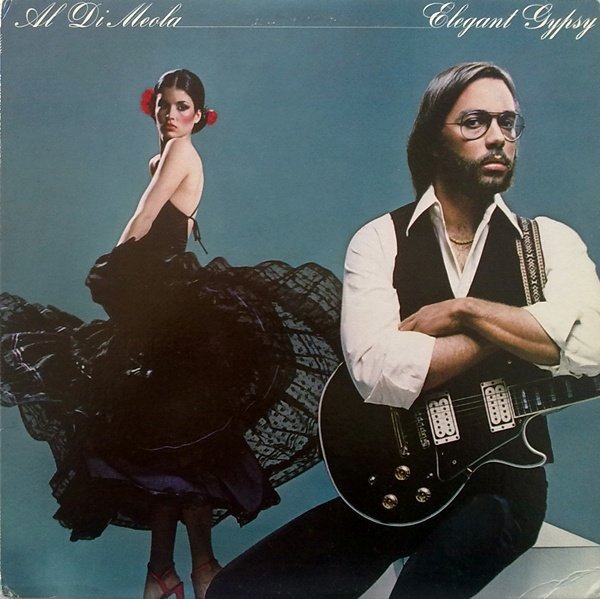

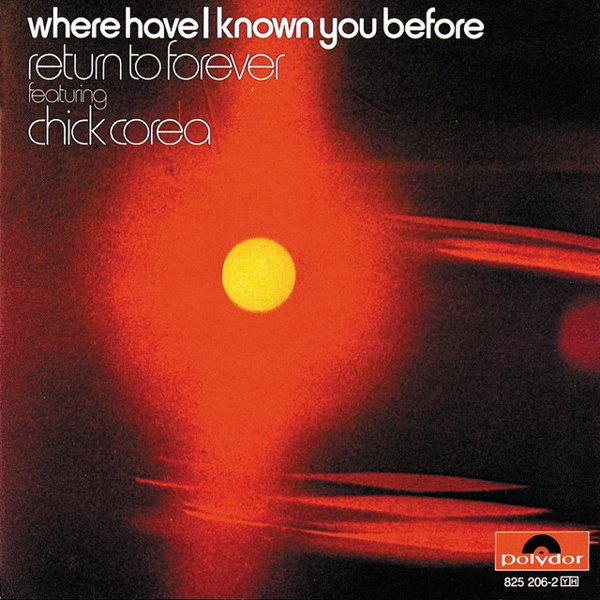

Several key Davis sidemen — keyboardists Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, and Joe Zawinul, saxophonist Wayne Shorter, guitarist John McLaughlin, and drummer Tony Williams — all struck out on their own, becoming prime movers in what was rapidly becoming a new New Thing. McLaughlin, organist Larry Young and former Cream bassist Jack Bruce joined Williams’ Lifetime; Corea, after a dalliance with the avant-garde in Circle, formed a group called Return To Forever; Shorter and Zawinul teamed up under the name Weather Report; and Hancock embarked on an extended romance with the creative possibilities of synthesizers and electric keyboards that has yet to end.

As fusion entered its glory years in the early to mid ’70s, the music became more elaborate and complex, with the improvisatory element sometimes taking a back seat until it became difficult to really draw a clear line between what the Mahavishnu Orchestra and Return To Forever were doing, and what King Crimson or Yes were doing at the same time. Some impressive cross-pollinations took place, as when McLaughlin teamed up with Carlos Santana for 1973’s Love Devotion Surrender, with Larry Young on organ and Mahavishnu’s Billy Cobham on drums, or when Cobham and keyboardist Jan Hammer joined the Fania All Stars on 1974’s half-studio, half-live Latin-Soul-Rock.

Depending which side of the street the players started out working, fusion could take on the showboating machismo of hard rock, or the deep grooves of funk. Players like keyboardist George Duke (who was in both Cannonball Adderley’s and Frank Zappa’s bands) and bassist Stanley Clarke proved to be both virtuoso players and serious funkateers, as did drummers Lenny White (Bitches Brew, Return To Forever) and Billy Cobham. By the second half of the 1970s, though, commercial success had sanded down a lot of the music’s edges and fusion was beginning to sound more like what it would eventually transform into…smooth jazz.