Boom bap is like the second amendment of hip-hop, an idea tacked on to an existing form and distorted over time into a fundamental principle that never existed. The boom of the kick and the bap of the snare were there before T La Rock ad libbed “b-boom, b-bap, b-boom bap” at the end of 1984’s “It’s Yours.” In fact, it hardly matters where the drums land for rap to qualify as rap. The only “original rap” definition you could posit and not look like a fool is “dance music with a guy saying rhymes over the top.” Eventually the rhyming guy became more important to the music than dancers, samplers replaced bands, and people started calling it “hip-hop” instead of “rap.” But there is at least one reason that the myth of boom bap as “original rap” persists—the golden era was that good. Whatever conservative retrenchment it engendered, the primary records of the boom bap moment are absolute corkers.

There were glimpses of boom bap from the beginning, eruptions of a style that was less hospitable to dancers and more suitable for rhyming. A live bootleg called “Flash It To The Beat” circulated for years, beginning in 1980. “Fusion Beats,” the more popular B-side, was a live recording of Jazzy Jay and Afrika Bambaataa juggling two frantic records, James Brown’s “Get Up, Get Into It, Get Involved” and “Champ,” by The Mohawks. On the flip was “Flash To The Beat,” ten minutes of Grandmaster Flash improvising on a drum machine at a medium pace while the Furious Five rapped a pre-written routine. It is blown out, primitive, not even in strict time. It is literally nothing but boom bap. When the group released a studio version of the tune in 1982, the words were unchanged but the whole thing was performed with a live drummer and bassist. It is fun but confused, one of the band’s least-loved singles.

The next step was Spoonie Gee’s minimal 1980 single, “Love Rap,” nothing but a drummer, a conga player, and Spoonie kicking game about his car with “seats so soft, just like a bed.” Run-DMC’s 1983 single, “Sucker MCs,” was the bigger bang, a drum machine made enormous with digital delay and two naturally enormous MCs. No melodic material, just swagger and stadium vibes like rap had never seen. These are fairly energetic songs, though, and suited for dancing. We had the reduction and focus of boom bap, but not the drag in tempo.

The minimal rap approach winds its way through the decade, as sampling enters in 1986 and hip-hop becomes genuinely popular. Eric B. & Rakim’s 1986 single, “Eric B. Is President,” is a decent place to date the beginning of actual boom bap records. It’s a heavy track with steady snares on the two and four and brief samples of the same records that were cut up for “Fusion Beats” (a significant reference). Rakim demonstrated that boom bap’s unfussy, slow rhythms were making room for a reason: rapping that was two levels up in terms of complexity. Rakim destroyed the barline and brought a metric sophistication to rap that buried the childish meter heard on Sugarhill and Enjoy records. The beat burrowed down to leave the sky open for the MC.

Audio Two’s “Top Billin’” came in 1987, the sort of Dada version of “Sucker MCs,” MC Milk barking while a drum machine stuttered and hovered between a swing and a stomp. A style was developing, slower than what we heard in the first decade of rap. There was enough memory now in some drum machines to store samples and this is central to the wilder sides of the form. Boom bap allows for strange, illogical loops, as long as tempos stay between 90 and 100 BPM. Snares still have to fall hard on the two and four, because this music is for nodding and listening—not dancing!

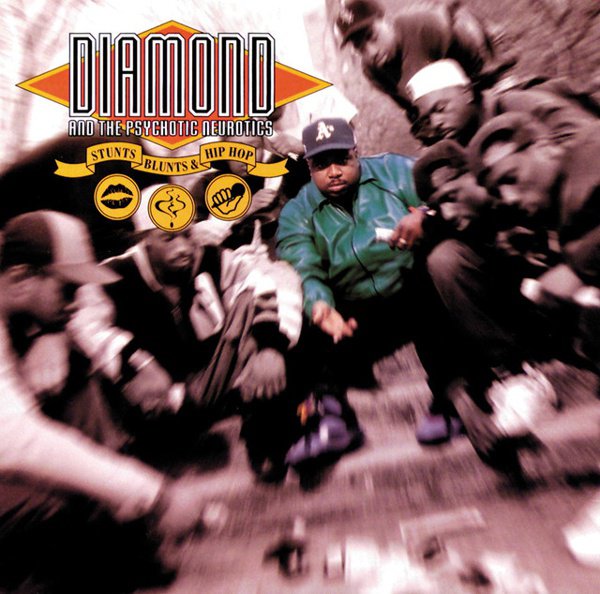

In the late Eighties, a group of producers had started getting a sound together after going through a dialectical struggle with what had come before. Raised on James Brown records, and then James Brown samples, these musicians had to formulate what came next. The names to look for are Q-Tip, Pete Rock, DJ Muggs, DJ Premier, Buckwild, J Dilla, The RZA, Da Beatminerz, Diamond D, Lord Finesse, Alchemist, and Large Professor. It’s interesting to consider who did and didn’t make the transition into the Nineties. Marley Marl, who mentored Pete Rock in the Eighties, started with the dirty James Brown template but transitioned into a slower, more sculpted sound and made several key boom bap albums. Public Enemy, on the other hand, a group that managed to be world famous for several years in the Eighties, was almost permanently erased from the playlists of hip-hop radio because they wouldn’t abandon their fast and noisy roots. Rap had to give up James Brown to move forward, and anyone who pledged allegiance was left behind. Acts like Jungle Brothers that flirted with house music and drum & bass also ended up on the sidelines. Boom bap was going to be slow and male and virtuosic in a very specific way. Fellas!

There are a few key samples that were used again and again and again. Skull Snaps’ “It’s a New Day” could be the DNA of boom bap. It’s a bowling ball of rhythm, compressed and unstoppable, with precise kick hits and a snare drum that might be full of marbles. Das EFX’s “East Coast” and the Pharcyde’s “Passin’ Me By” were two big early Nineties hits that used the Skull Snaps, and there are dozens of others. First heard by many on the 1986 Ultramagnetic MCs single, “Ego Trippin’,” the beat from Melvin Bliss’ “Synthetic Substitution” became a favorite of the RZA (who used it almost twenty times). There’s both delicacy and menace in the kicks, and in the melting tempo, like it’s a fast song trying to grab the rail and decelerate. Gang Starr’s “DWYCK” and Wu Tang Clan’s “Clan In Da Front” are two well-known early Nineties tracks that use the Bliss beat. (There are Spotify playlists for songs that sample these beats.) Other boom bap staples were Sly & The Family Stone’s “Sing a Simple Song,” and The Five Stairsteps 1968 single, “Don’t Change Your Love,” a Curtis Mayfield production with giant, echoing drums. You can hear the Stairsteps sample on A Tribe Called Quest’s 1991 single “Jazz (We’ve Got),” and after that, everywhere.

The boom bap run in the first half of the Nineties was a hot streak, a third championship ring for New York after the invention of the form itself and the Jordan-level achievements of Rakim. Boom bap would also be the last significant New York contribution for a while, too, possibly until Pop Smoke and the Brooklyn drill of the late teens. A Tribe Called Quest, Gang Starr, Wu Tang Clan, Pete Rock and CL Smooth, EPMD, Mobb Deep, and the early days of Biggie and Jay-Z—these are the heirloom seeds of boom bap.

This approach made rap into a crate digger’s music, creating parameters that were simultaneously wide open and oddly constrained. The producer could sample almost anything—this is pretty much the working mantra of DJ Premier—but they had to jam all of that sound into a brief loop which could be futzed with, but only to a point. The sample could handle the texture and surprise but the MC would have to take care of rhythmic variation, and maintaining a consistent tone was encouraged. Rap had become hard bop, more or less, a music for formalist improvisers and killer timekeepers. The conversation began in shops like Rock and Soul in Midtown and Fat Beats in Greenwich Village, but the Supreme Court was The Stretch Armstrong and Bobbito show, which broadcast for most of the Nineties on WKCR 89.9 FM. The night in February of 1995 when Big L brought Jay-Z to the studio is sort of the moonshot of boom bap, and that was a Stretch and Bob moment.

Boom bap had bragging rights over the South and West, which was a shame, because that’s exactly where the artform and audience went. New York City’s mulish pride stranded boom bap in the 20th century. Dr. Dre’s West Coast G-funk appealed to the car culture of America more than New York rap, which may have been made for jeeps but didn’t convince a lot of people outside the tri-state area. By the end of the Nineties, the big stars were rooted in styles of the South and West: think Eminem and Outkast. Das EFX faded from the discussion faster than Dukakis and upright bass samples have really never come back. In the late nineties, boom bap was a bit like punk rock, as independent labels turned out slavish traditionalism that redefined monochrome and fell way short of the shiny rap on the radio. (I will never not love Mase.) Boom bap became the anti-fun style of rap.

Rap in the twenty-first century has largely been about working variations on Southern templates, like trap. Boom bap has become a diasporic form, not really itself, nor should it be. Most of the variants are still on the East Coast, but not all of them. There’s a lot of boom bap in Pharrell Williams productions, most obviously Clipse’s “Grindin’” but not just there. His super-sized cinderblock drums are right out of the Nineties playbook. El-P worked with Company Flow, who plausibly could be called first wave boom bap. He took the EPMD dirt sound and spun it into a painful kind of psychedelia, and with Run The Jewels, he’s come all the way back around. A recent single, “Ooh La La,” not only sounds like pure boom bap, it features DJ Premier and Greg Nice, so it just is boom bap. Like El-P, Alchemist has never stopped working, and is now one of the elders of the form. The field is still susceptible to a retrograde blend of maleness and grouchiness, but there is a whole cohort of people who belong now to the family: everyone on the Griselda label, Roc Marciano, Freddie Gibbs, Trust Gang, and Action Bronson, to name a few. As long as men want to complain and avoid dancing, boom bap will live on.

I’ve jammed almost all of this into an overly long Spotify playlist. The full garbage bag feel is there to let the music wheel around and mean less, if you catch my drift. How do I know what boom bap is now! I only know what it once was.

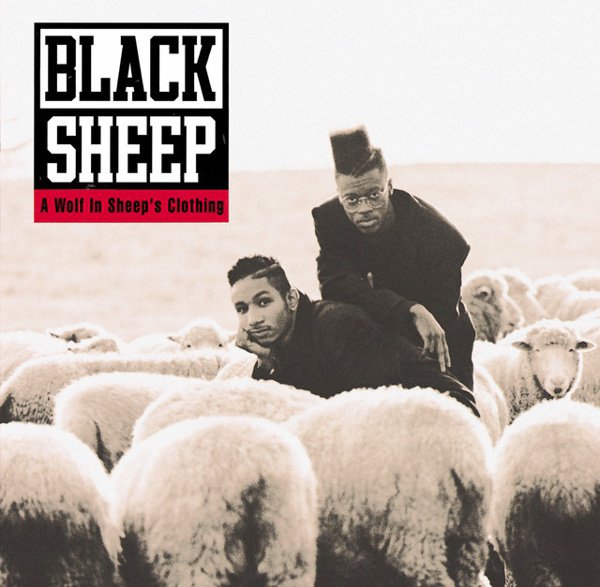

TEN BOOM BAP ALBUMS YOU WILL LIKE

I’ve skipped Enter the Wu Tang, Ready To Die, The Infamous, Illmatic, and The Low End Theory, because you should have those already. You don’t know Double XX Posse? The most boom bap act of all time!