The loft jazz era lasted from the late ’70s to the early ’80s, but by 1983, avant-garde jazz was in dire straits in the US. Artists like Arthur Blythe, Anthony Braxton, Tim Berne and Henry Threadgill, all of whom had been signed to majors, were dropped; others, like Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman, released their work on European labels (as did Braxton, since no one imprint could keep up with his output). Were it not for the Italians and Germans, releasing the music on Black Saint, Soul Note, ECM and MPS, avant-garde jazz might have died out completely in the ’80s.

The situation began to improve slightly as the ’90s began. Taylor released In Florescence, a trio session with bassist William Parker and percussionist Gregg Bendian, on A&M; Threadgill put out Makin’ A Move and Where’s Your Cup? on Columbia; Coleman signed with Verve and put out the final Prime Time album, Tone Dialing, followed by a matched set, Sound Museum: Hidden Man and Sound Museum: Three Women, and Colors: Live In Leipzig after that. All four featured keyboards (Geri Allen played piano on the Sound Museum discs, and Colors was a duet with Joachim Kühn), something the saxophonist had abjured for nearly four decades at that point. Verve also reissued several of his 1970s discs, allowing them to reach a wider audience.

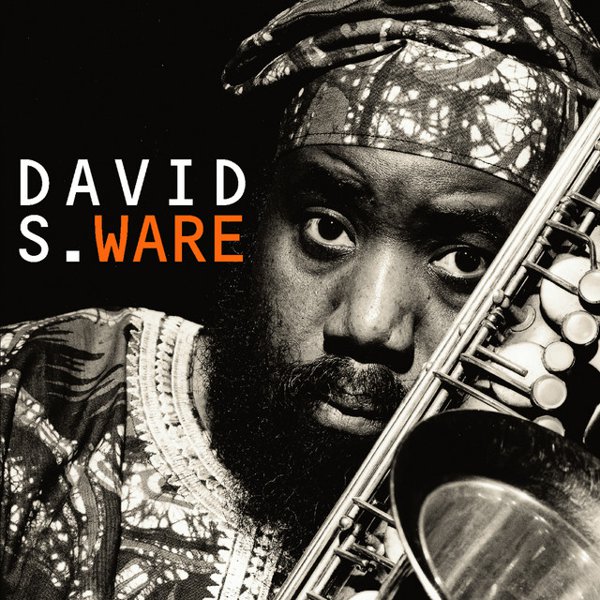

The real action, though, was in New York’s East Village, where a new generation of players was creating their own scene. One key figure was saxophonist David S. Ware, a veteran of the loft scene who’d formed a new group with pianist Matthew Shipp, bassist William Parker, and a string of drummers: Marc Edwards, Whit Dickey, Susie Ibarra, and finally Guillermo E. Brown. The quartet’s music was titanic, seemingly picking up where John Coltrane had left off in 1964 but journeying out into high-energy improvisatory realms that left even fierce players like David Murray and Pharoah Sanders sounding tame and placid. Ware recorded for multiple labels: DIW, Homestead (which explored free jazz briefly just before shutting its doors in 1996; its final manager, Steven Joerg, founded AUM Fidelity, and continues to release brilliant, adventurous music to this day), and Silkheart, before Branford Marsalis, of all people, brought him to Sony/Columbia. Shipp and Parker made albums on their own, sometimes working together and other times apart, and other players like saxophonist Charles Gayle, guitarist Joe Morris, trumpeter Roy Campbell, Jr., and many others emerged as well. Outside New York, free jazz seemed to be having a moment as well; a strongly collaborative scene emerged in Chicago, where veterans like Fred Anderson encouraged and mentored younger players like Ken Vandermark and Matana Roberts. German tenor titan Peter Brötzmann was so enamored of the scene, he rounded up many of its best players for his Chicago Tentet, which toured the world until 2012, releasing more than a dozen albums along the way.

The most surprising part about the ’90s free jazz renaissance, which lasted well into the new century, wasn’t that the music was great; it was that the music press paid attention. Ware and Gayle landed a co-lead review in Rolling Stone and with well-timed endorsements from Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth (who hired the Ware quartet to open for them), members of Yo La Tengo, and others, free jazz drew the attention of indie rock fans and critics. Reissue programs brought long-forgotten albums back into stores, and veterans like Anderson, Brötzmann, Joe McPhee, Sun Ra, the Art Ensemble of Chicago and more began performing to rooms full of young, excited faces.