Douglas Wolk once referred to Sonic Youth as “comp sluts,” for the number of tribute anthologies they appeared on during the nineties, and as a listener, that’s what I am too. So it’s worth noting up front that what I’m writing about here isn’t African music, per se, but African compilations as compilations—a specific format that evolved commercially in a particular way.

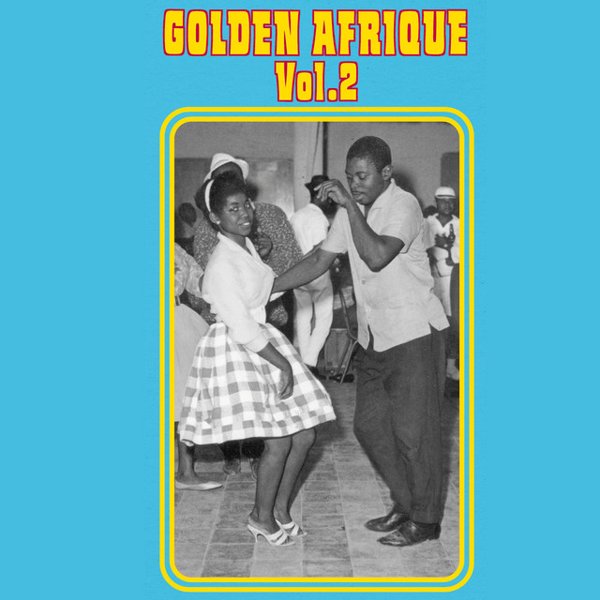

For a long time, compilations were the easiest and most bountiful route into classic African pop for American fans, as important or more than artist albums, since only a handful of individuals had made much of a dent, such as Fela Kuti, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, and Youssou N’Dour. Especially as the CD overtook the vinyl LP in the late eighties, and opened up the music market even more widely, compilations of all sorts flourished, from archival box sets to dance DJ mixes. Also, Africa’s gigantic, making an expert’s selections even more helpful.

Note the word “pop” above—it’s not casually chosen. For years prior to the eighties, ethnographical recordings from Africa were more widely available in record stores than collections of songs people bought and heard on the radio—far more. To give you an idea of how modest was African pop’s commercial prospects in the States, John Storm Roberts, the founder of Original Music—whose 1973 collection Africa Dances is the starting point for this particular area of focus—told Robert Christgau in 1990 that his break-even point for a title’s sale was a modest 750. That’s not a typo—seven hundred and fifty, and not all his titles did as well.

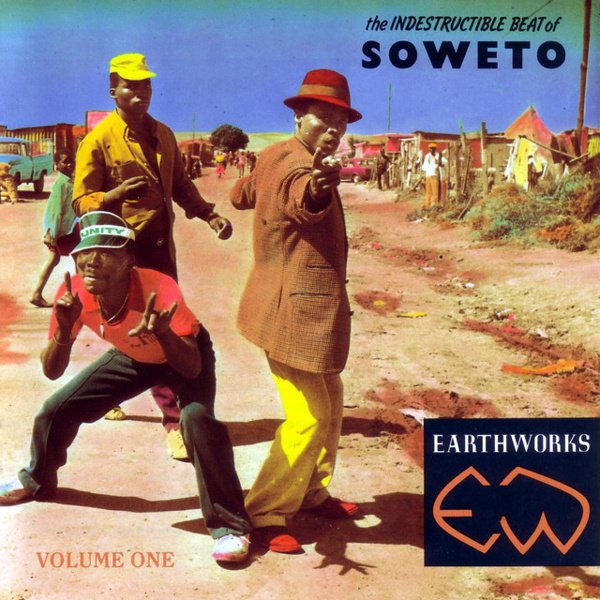

Granted, three decades is a long time, particularly in the music business. Still, given the subsequent internationalization of US pop for its producers and audience alike, that number seems absurdly small. It did then, too: “We’re not into niche marketing or being on top of some world-music chart,” Jumbo Vanrenen, the co-founder of Earthworks Records and an A&R man for Chris Blackwell’s Island Records subsidiary, Mango, told Billboard in 1996. “We’re trying to break these acts into the mainstream.” But as localism has become easier to access, and well after the playlist became both a primary pop conduit and more widely shareable, the kind of niche appeal of compilations also seems right.

Comps have long been the way the record biz tests the waters, and when Mango Records decided to try its hand at selling African pop to westerners in the early eighties, including three acclaimed LPs by the Nigerian juju master King Sunny Adé, one of the label’s executives told a reporter, “We think it’s the coming thing, this kind of third world music. We’re starting with a zero base, after all.”

That earlier positioning is important to remember, because it was a definitively pre-Internet time, and information on this music was hard to come by in the U.S. But the nineties’ CD boom took collections of African pop along with it, along with all manner of global pop, from the Alps to the Sahara. Throughout the decade, seemingly every major label had a global-music subsidiary that pumped out compilations. In 1991, Yale Evelev, the president of Luaka Bop Records, emphasized to Billboard that it was “a label of popular ethnic music, not a label of folkloric music.”

But that touristy sense pervaded all sorts of the most successful compilation CD series of that period, from the mild-mannered coffeehouse exotica of the packages from Putumayo to the more scholarly mien of the highly reliable Rough Guide series, tied to a travel-book series and venturing into vintage Americana, as well as every conceivable area of African pop.

That set the table for the 2000s, when the number of African pop comps sharply increased in number and profile. Labels like London’s Soul Jazz and Strut, in particular, became adept at packaging Nigerian music in particular, and Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat seeped more directly into clubland, cf. “MAW Expensive,” Masters at Work’s 2003 house-music reworking of his “Zombie.” The 2008 success of the Fela! musical played another part. But so did a generational shift: Reissued obscurities were part of an omnivorous listening diet, and so was music from anywhere at all.

The reissue producer Andy Zax neatly summarized things this way: “A compilation is like an essay. A good compilation has a thesis; a bad compilation doesn’t.” Some of the best of these have the sweep of history; others are then-and-there overviews with revelatory snap. In a few cases, they share a song or two, but even then, these collections don’t much resemble one another. But as much as the best music itself, from the fluid peal of Congolese rumba and soukous to confidently bumptious South African mbaqanga and disco to turn-of-the-millennium African hip-hop, the best compilations all have their own personalities.