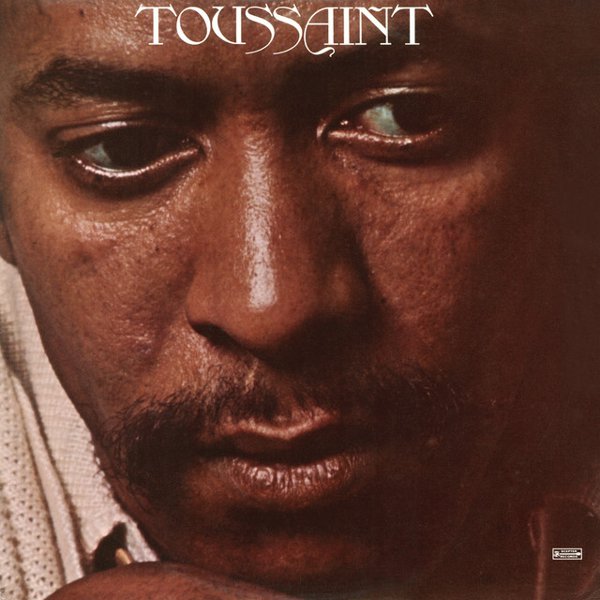

If you were to try and capture the sound of America using the music emanating from only one city, New Orleans would be the place. The birthplace of jazz as well as Cajun music, the town where country blues met brass bands, where African, Cuban, Caribbean, and Amerindian rhythms swirl and eddy and raise up all of it. It’s a sound impossible to boil down to a singular essence, but Allen Toussaint comes closest to embodying the entire musical gumbo. No one epitomized the many strains of the Crescent City like Toussaint. His vast songbook is sweet, vibrant, festive, and indelibly New Orleans. As a producer, A&R scout, arranger, songwriter, and reluctant artist himself, Toussaint exemplified every aspect of the city: its deep history, its Creolized musics, its rhythms (bouncing from the playground to the boudoir and back), its bright pageantry and country plainspokenness.

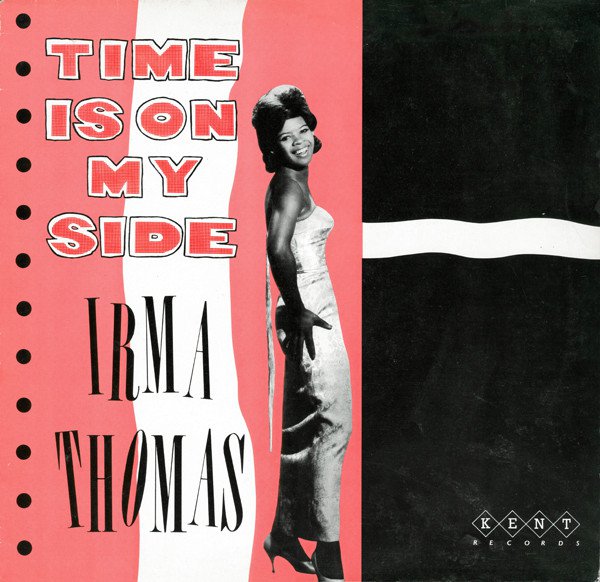

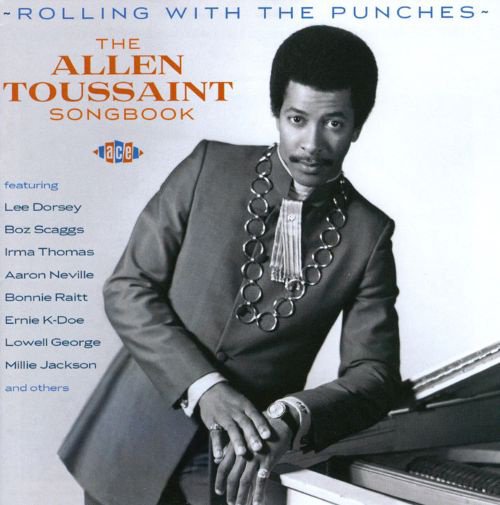

How influential is the man? Try to imagine an alternate – albeit far less joyously musical – universe, where Allen Toussaint is drafted into the US Army to serve in 1963, never ever to return to music-making. No more session work on the piano, no more sheet music bearing his penciled-in charts, no more songwriting credits. Even with that cut-off date, Toussaint’s fingerprints would still linger over American and British popular music. As penned by the young Toussaint in the early ‘60s, numbers like the punchline pop of Ernie K-Doe’s “Mother-In-Law,” Irma Thomas’s “It’s Raining,” and Lee Dorsey’s “Ya Ya” (as well as a two-sided doozy for singer Benny Spellman, “Lipstick Traces (On A Cigarette)” b/w “Fortune Teller”) kindled the imaginations of listeners on both sides of the pond and codified the sound of New Orleans for future generations.

Thankfully, Toussaint was discharged in 1965 and got right back to it, his work ethic providing our universe with a veritable King Cake of wit, sophistication, funk, and elegance. In terms of inspiration and determination, it’d be hard to top the tune Toussaint penned for the great Lee Dorsey – a song later covered by the Pointer Sisters and then appropriated by a certain presidential campaign – “Yes We Can.” Then there’s the tongue-in-cheek raunch of “Ride Your Pony,” the strip joint anthem. Sure, the Band might have written “Life is a Carnival,” but it’s Toussaint’s horn charts that make it feel like you’re in the middle of one strutting through Bywater.

Born in 1938 in Gert Town, the Mid-City district that the legend Buddy Bolden once called home, Toussaint’s father worked in the railroads and played trumpet, while his mother (whose maiden name, Naomi Neville, Toussaint would use as a songwriting pen name) got him piano lessons as a child. Post-war New Orleans was a boon for pianists, Professor Longhair’s heavily syncopated “second-line” style of playing exerting the biggest influence on a generation of musicians. By 17, Toussaint was gigging around town, at times subbing in for the likes of Fats Domino and Huey “Piano” Smith.

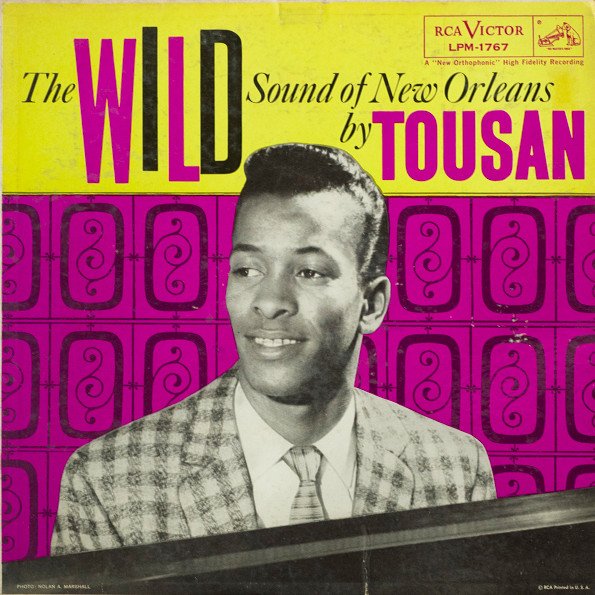

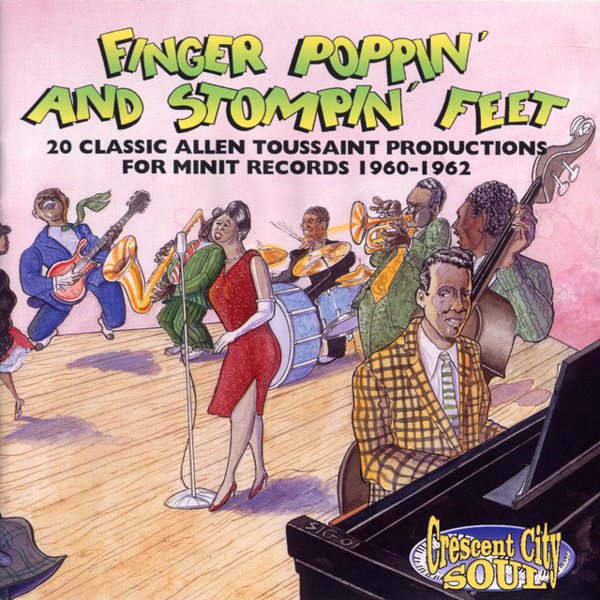

Toussaint (as “Al Tousan”) also cut his first album in 1958, a set of instrumentals titled The Wild Sound of New Orleans. It contained a jaunty little tune called “Java,” which would become a hit and Grammy Award for trumpeter Al Hirt six years later. (Six years after that, Jamaica’s Augustus Pablo voiced it through his melodica, making Toussaint’s “Java” into a keystone of dub reggae.) Joe Banashak of Minit Records tapped Toussaint as a Swiss Army knife for his label, Toussaint serving both as A&R man and producer. The likes of Ernie K-Doe, Spellman, Thomas Art and Aaron Neville, The Showmen, and Lee Dorsey all passed through those studio doors.

After that army stint, Toussaint teamed up with business partner Marshall Sehorn. Together they formed both a record label and company named Sansu (as well as sub-labels like Tou-Sea and Deesu). The hits kept coming and Toussaint’s writing was at a peak. It didn’t hurt that he had cobbled together some local kids to serve as house band for these sessions. This group of New Orleans teens – keyboardist Art Neville, guitarist Leo Nocentelli, bassist George Porter Jr., and drummer Zigaboo Modeliste – would work in the studio by day and tear the roof off the clubs at night as the Meters. Loose, precise, righteous, moving from a simmer to full boil and back as they cooked up New Orleans funk every night. A band, as writer/poet Hanif Abdurraqib put it, “invested in wonder, in exuberance, in the kind of delightful childlike awe of finding a miracle around every corner.” They gave Toussaint and a rotating cast of singers the kind of unbridled power necessary for the years ahead, their funk serving as a template for all things New Orleans.

Having reminded the world that New Orleans remained a musical world power, in 1973 Toussaint opened his own Sea-Saint Studios, which in addition to codifying locals like Dr. John and The Wild Tchoupitoulas in the national consciousness also welcomed outsiders like Paul McCartney and Wings. And like tufts of dandelion, Toussaint’s songs began to spread far and wide, becoming hits for the likes of Bonnie Raitt, the Judds, and Glen Campbell. What is “blue-eyed soul” without the Black man penning numbers soon covered by svelte white boys like Warren Zevon, Boz Scaggs, Van Dyke Parks, and Robert Palmer?

Just because Toussaint could root down and get to the themes of the heart that effortlessly crossed the color line doesn’t mean he couldn’t also write social critiques as astute as those penned by critically-revered peers like James Brown, Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye or Gil Scott-Heron. First, there’s an anthem like Lee Dorsey’s “Yes We Can” (which would wind up first on the charts thanks to the Pointer Sisters and then as the theme to Barack Obama’s historic presidential campaign). And then the pointed and poignant “Freedom for the Stallion,” which cries out: “Lord, have mercy, what you gonna do/About the people who are praying to you? They got men making laws that destroy other men.” Has anyone ever utilized the cycling verse-chorus-verse to detail the brutal purgatory of blue collar work as well as “Working in a Coalmine” and yet remained as buoyant while doing it? Aaron Neville’s “Hercules” feels smooth and silky, at least until stinging lines like “If you’re not gonna help, don’t hurt/Just pass me by” start to land.

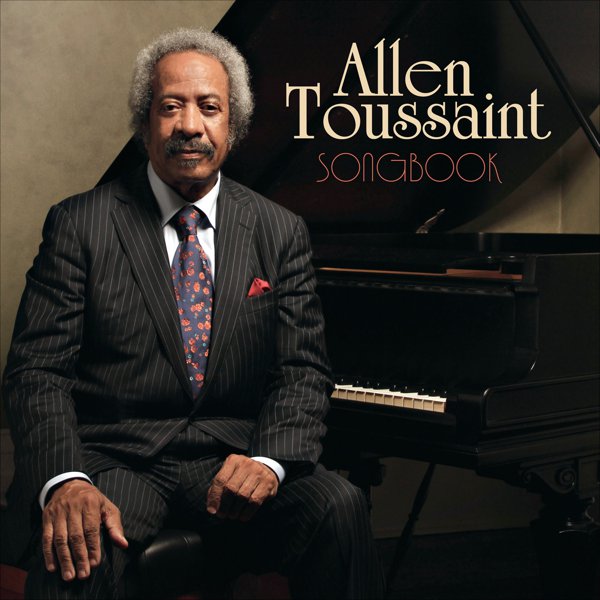

In his later years, Toussaint himself came to embody the struggle of his city. His home and studio were destroyed in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, putting the burden of his city on his shoulders as he began to perform in earnest. Intimate concerts at Joe’s Public, bigger concerts at Carnegie Hall as well as international tours, Toussaint soon became the face of New Orleans, his struggle doubling as the city’s struggle as both he and it attempted to rebuild from the floods. Even in the years after his passing, Toussaint remains the sound of New Orleans. You can start almost anywhere in his catalog and immediately hear a second line parade stir to life, capturing not just the joy but also the hurt and desperation that underpins the most ardent celebrations of the city.