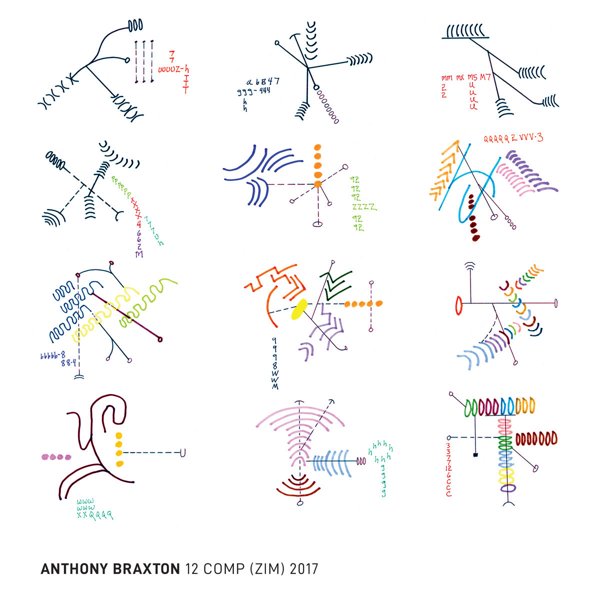

Anthony Braxton was born in 1945 and grew up on Chicago’s South Side, as fascinated by technology as by music. (There’s a reason his compositions are often represented — “titled,” if you like — by what look like wiring schematics.) He joined the Army after high school, and when he returned to Chicago after spending time in South Korea, he heard about the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, and was invited to join by Roscoe Mitchell.

His 1968 album 3 Compositions of New Jazz, as declarative and prophetic a title as Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come, introduced an entirely new compositional voice. That was quickly followed by For Alto, a double LP of solo saxophone pieces dedicated to John Cage, Cecil Taylor, Leroy Jenkins, and others. Braxton has spent his entire career developing and exploring a few key concepts, one of which is what he calls “trans-idiomatic” music-making, which amounts to a refusal to recognize a dichotomy between composition and improvisation. His core methodology is “language music,” which consists mostly of a set of twelve essential ways of playing (long tones, trills, multiphonics, legato formings, etc.) which can be combined or pitted against each other depending on the mood of the moment, but also includes two strategic parameters — “gradient formings,” in which a quality of the music changes over time (e.g., it gets faster, or it becomes more staccato), and “sub-identity formings,” in which a musician or musicians can shift from one composition to another, inserting it into (or playing it against) what the rest of the ensemble is already doing.

Understanding the conceptual underpinnings of Braxton’s music is key to wrestling with his massive discography. His work can be grouped under a few umbrellas, though there are outlier albums in every era. In the 1970s, he first led a group with trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith, violinist Leroy Jenkins, and percussionist Steve McCall; pianist and AACM founder Muhal Richard Abrams occasionally joined them. He later formed a quartet with bassist Dave Holland, drummer Barry Altschul, and various front-line instrumentalists, trumpeter Kenny Wheeler and trombonist George Lewis most prominent among them. Braxton, Holland and Altschul were joined by saxophonist Sam Rivers for the bassist’s classic 1973 album Conference Of The Birds.

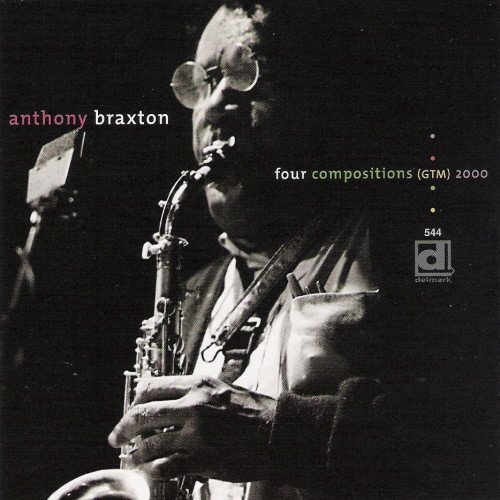

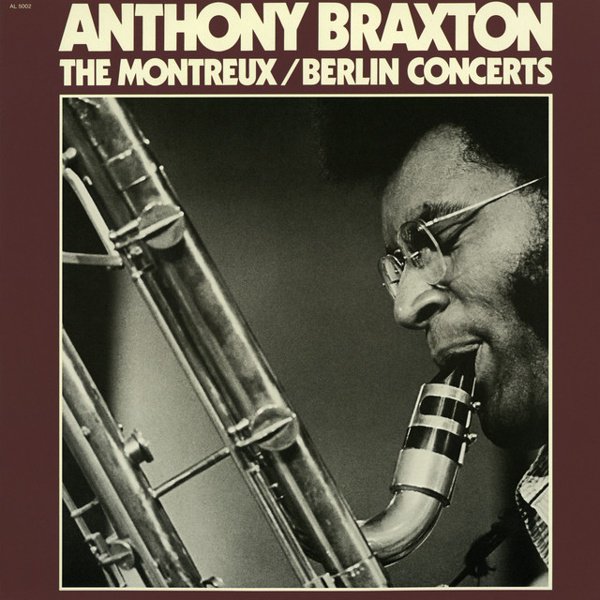

An Arista Records contract allowed Braxton to release the almost conventional quartet discs New York, Fall 1974 and Five Pieces 1975, as well as the massive For Four Orchestras (yes, playing simultaneously) and the brilliant double live LP The Montreux/Berlin Concerts. His output has always been too much for any one label to handle, though, and he’s had long, overlapping relationships with Black Saint, Leo, and hatART, while also releasing titles through his own Braxton House and New Braxton House imprints. In the 1980s, he led a notable quartet with pianist Marilyn Crispell, bassist Mark Dresser, and drummer Gerry Hemingway. They didn’t enter the studio until 1993, but a UK tour in 1985 yielded four live releases (on Leo) and a book, Graham Lock’s Forces In Motion, possibly the best introduction to Braxton the man and the musician available, and that includes his own extensive writings.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Braxton’s music became increasingly complex and theory-driven, and he frequently assembled ensembles of nine to more than a dozen members, while also performing solo and in duos with a broad range of partners. The extraordinary talent of his collaborators has made the results vivid and thrilling, even as he seems to have shifted from releasing individual albums to dropping massive boxed sets on the listener — 9 Compositions (Iridium) 2006, for example, is a nine-CD set of live recordings with a 13-member ensemble, and it’s great, as long as you only try to get through a single hour-long composition at a time.

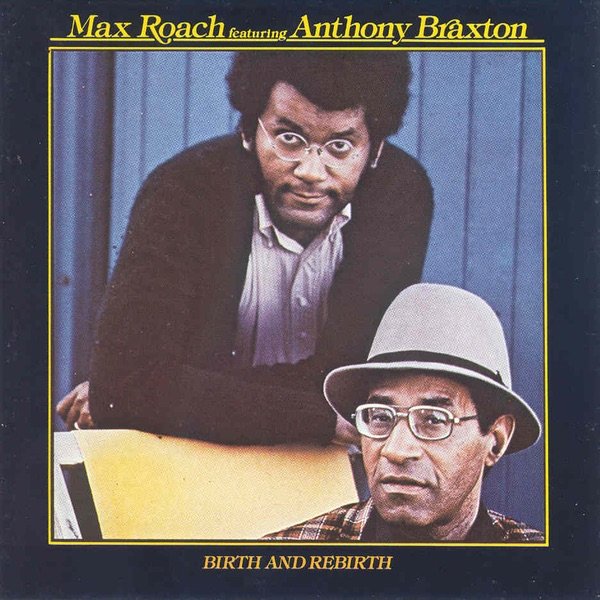

While writing seemingly nonstop, Braxton has frequently taken time to demonstrate a deep love for the jazz tradition. He has recorded albums of music by Thelonious Monk and Lennie Tristano, as well as numerous collections of standards, often in collaboration with musicians who are not part of his regular ensembles. He’s also popped up as a guest in some surprising places, including a mid ’70s Dave Brubeck album and a live collaboration with Detroit electronic noise act Wolf Eyes.

A catalog as deep as Braxton’s is destined to go unappreciated; there’s just too much for one person who’s got anything else going on in their own life to ever hear it all. But Braxton is more concerned with doing the work than with who might eventually hear it. As he told me when I interviewed him in 2021, “I’ve approached my music in a way that’s slightly different than the jazz musicians and the classical musicians. I wanted to have an experience, I wanted that experience to be trans-idiomatic as opposed to mono-idiomatic, and I wanted to learn how to use my processes in a way that continues to evolve the kind of things which excited me. And so if one person comes who likes only one composition that I’ve done, I will be very happy, because no one owes me anything.”