‘Blaxploitation’ is a blanket term for early seventies films made by Black directors and aimed at Black audiences. The films were generally independent, low-budget and their subject matter was often crime, drugs, sex and racial tension. The genre included a broad range of films so it can be problematic to generalise, but blaxploitation movies have often been accused of glorifying violence and perpetuating stereotypes of Black communities. While this may be true in some cases, the films were also extremely popular with their audience and were vital in the development of the Black film industry while providing creative outlets for Black actors and directors.

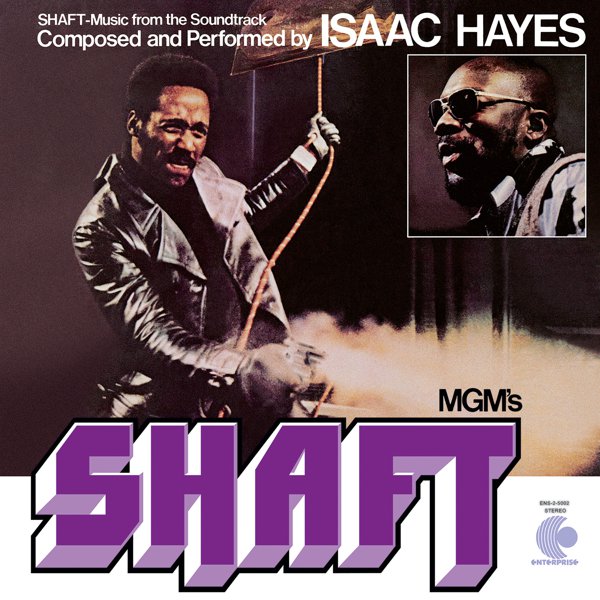

Musician and writer Questlove in his book Music Is History notes the tension within the blaxploitation genre, saying that for many they were “exciting, thrilling and even inspirational” but describing early blaxploitation classic Shaft as “…if not an overt tool of white control, a perfect example of of the way that the white hegemony had forced black people to internalise stereotypical ideas of themselves.” The complex impact, influence and meaning of the blaxploitation genre is a subject probably best left to experts. However, aside from the films themselves, there were the soundtracks, many of which were superb.

The early seventies were an incredibly fertile period for soul and funk music. Studio technology had progressed to enable high-quality multi-track recordings while new gear like synthesisers and effects units like phasers, chorus, envelope-followers and wah wah pedals broadened the scope of what was musically possible. Many black artists were stretching out and including new influences from psychedelia, jazz and Latin in their music, expanding the sonic language of R’n’B.

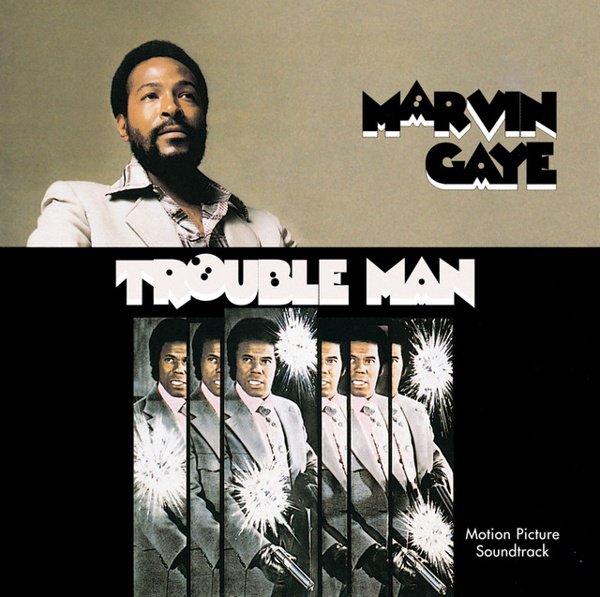

The increasing popularity of the album format also encouraged experimentation in songwriting and production too. In his seminal book, The Death of R’n’B, author Nelson George refers to a new sophisticated musical sensibility that emerged during the early seventies, where Black music became “longer, more orchestrated, more introspective — some Black albums had the continuity and cohesions of soundtracks even when they weren’t. Latin percussion in the form of cowbells, congas and bongos suddenly became rhythmic requirements, adding a new layer of polyrhythmic fire to the grooves. Minor chords, frowned upon during the soul years, began appearing in the work of Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, and the proliferation of black bands such as Earth Wind and Fire, Kool and the Gang and Mandrill.”

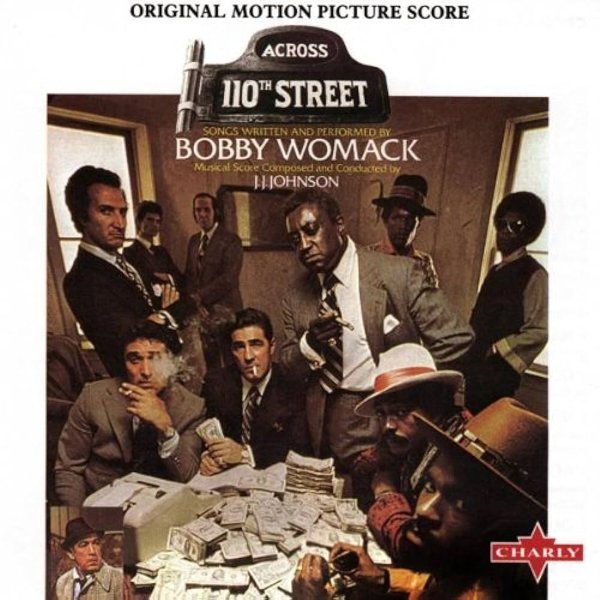

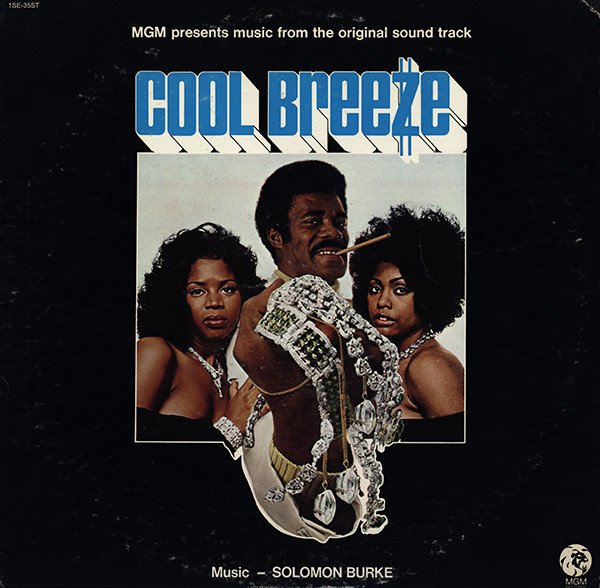

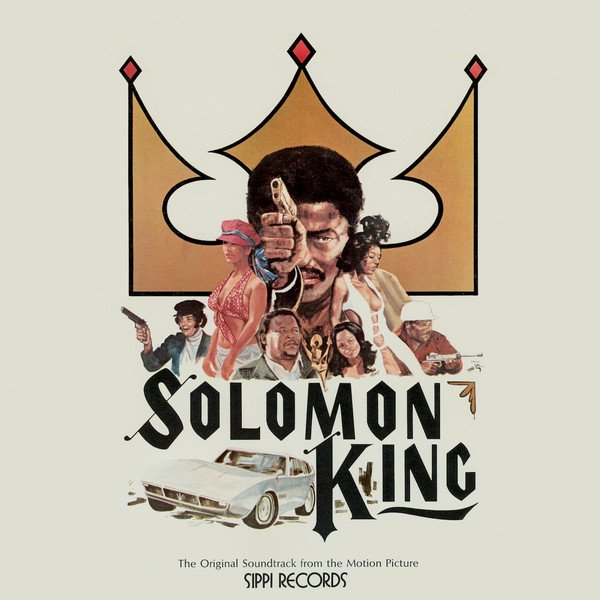

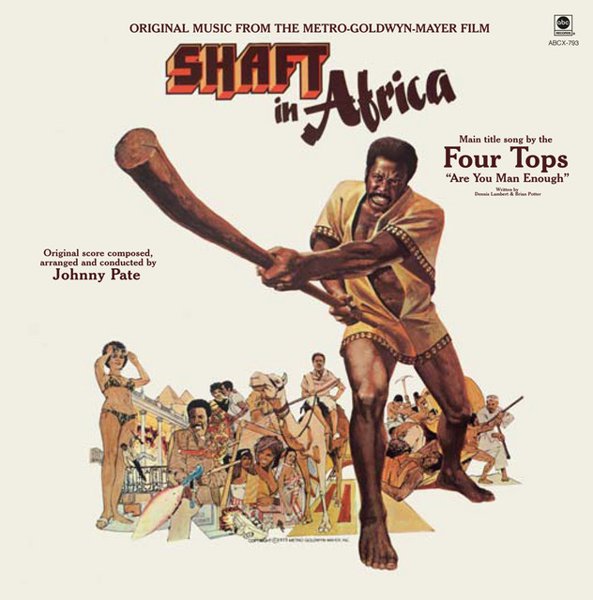

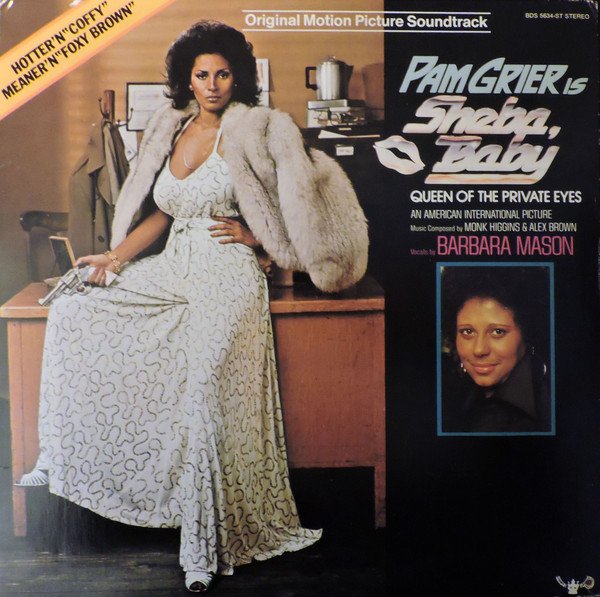

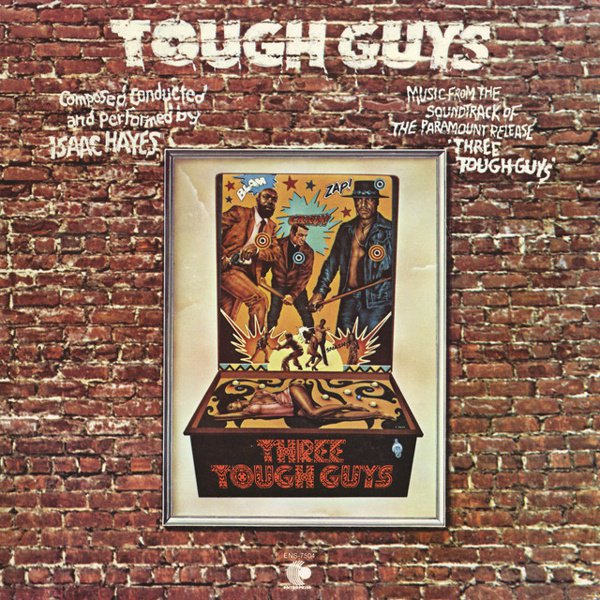

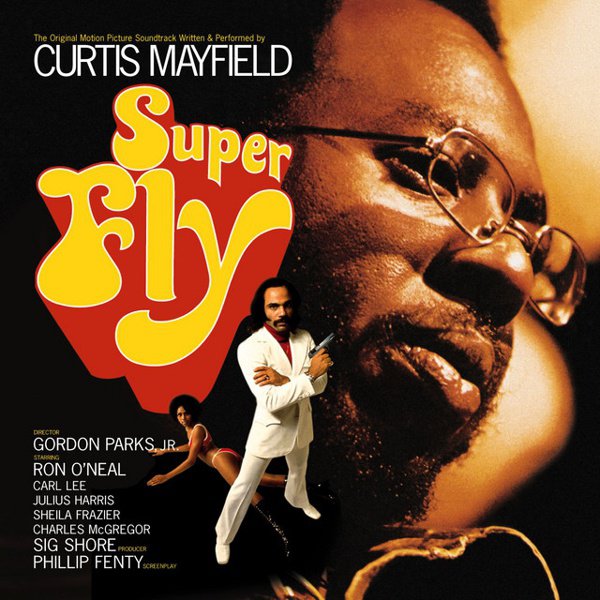

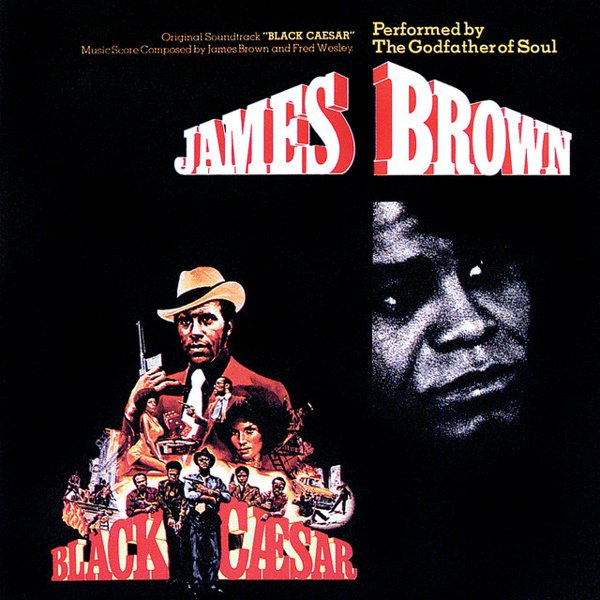

It was in this creative atmosphere that artists like Willie Hutch, Isaac Hayes, Bobby Womack, Roy Ayers, Grant Green, Edwin Starr, Johnny Pate, James Brown and Curtis Mayfield produced many enduring and sophisticated soundtrack albums for the films that would later be called blaxploitation movies.

Films require music for every mood, so the soundtrack albums were often expansive, bold and highly inventive. Rickey Vincent in his book Funk: The Music, The People and the Rhythm of the One notes that “The black film formula was a ready-made recipe for the black musician to explore the range of black American life and express it in song. Each soundtrack featured a snappy and radio-friendly intro theme, chase scene music, romantic or sexy love scene sounds, and music for funerals, weddings, stealthy suspenseful moods and bloody action.”

Composed by some of the most successful and influential Black artists, played by superb musicians at the very peak of their game, in an era of musical confidence and experimentation, Vincent is absolutely correct when he says “Soundtrack albums produced a level of variety and consistency that rivalled the great funk bands of the era.”

Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Badass Song from 1971 is considered by many to be the first blaxploitation film. The soundtrack by Earth Wind & Fire is heavily punctuated by sound effects and dialogue from the film and isn’t the best of the genre. However, later that year, Isaac Hayes released the soundtrack to Shaft, the first double album from a soul artist, which became the best-selling release in Stax Records’ history and won four Grammys. Curtis Mayfield’s seminal Superfly followed in 1972, and both albums were much-copied exemplars of the soul and funk film soundtrack. Over the next few years there was an abundance of blaxploitation projects, plenty of which came complete with soaring soundtracks.

Over time, many of the musical innovations of these albums found their way into pop music, TV themes and adverts and by the end of the seventies, the wah wah guitar, conga-heavy, highly-orchestrated and elongated funky rhythm tracks that characterised blaxploitation movies had become clichéd. But many of the soundtrack albums stand up extremely well today, full of sophisticated, adventurous and confident soul, jazz and funk.

![The Final Comedown [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5768082178441216_v2_600.jpg)

![Hell Up in Harlem [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5674138202013696_600.jpg)

![Coffy [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5713266649071616_600.jpg)

![The Mack [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5762036045709312_600.jpg)

![Slaughter's Big Rip-Off [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/6241823194873856_600.jpg)

![Short Eyes [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5175457088012288_600.jpg)

![Brother On The Run [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/4815156912062464_v2_600.jpg)

![Truck Turner [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/6232414062379008_600.jpg)

![Lialeh [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5078044142731264_600.jpg)

![Foxy Brown [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5356474947600384_600.jpg)