Few creatively distinct yet compatible art forms have intersected in ways as simultaneously natural and conflicting as cinema and jazz. That relationship is literally the confluence of the first-ever “talkie” in 1927 — and since that talkie was The Jazz Singer, whose titular role was played by Al Jolson and involved blackface performance, the questions and conflicts over depictions of the music and its culture were there literally the moment that relationship was made technologically possible. And while jazz would remain a major part of Hollywood’s aesthetic palette for as long as it remained a popular concern — scoring numerous oddball animated shorts of the ’30s, driving the beat of the occasional Broadway adaptation, popping up in musical-interlude cameos for romantic comedies and hard-boiled dramas — it was still treated as an end rather than a means: jazz appearing on film primarily in performance, to showcase the music, to be about jazz. In other words, taking advantage of film to showcase the music’s qualities, rather than using those musical qualities to comment on the events of the film.

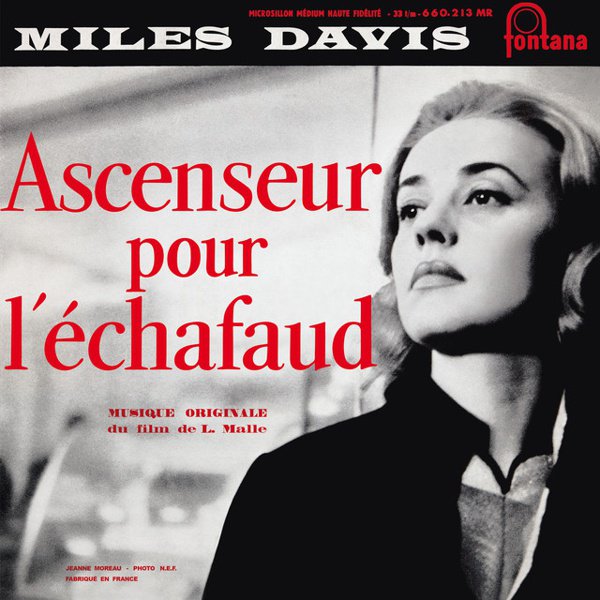

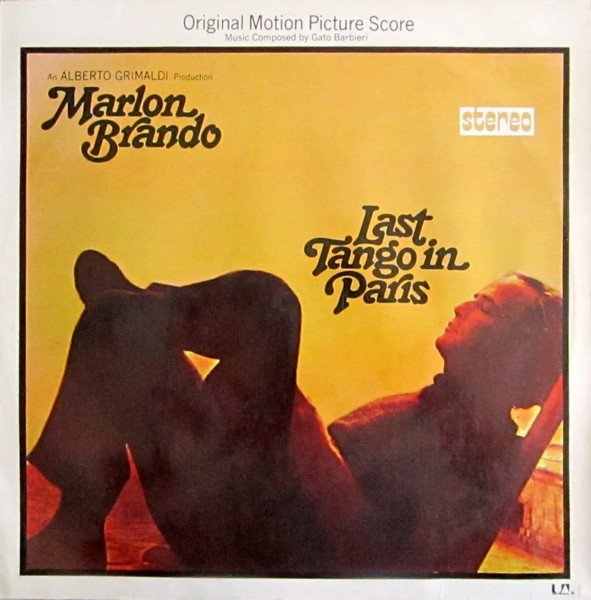

But something shifted in the postwar years — a notion that began to take hold around the time that jazz entered a phase of growing maturity, rapid creative evolution, and a tenuous but emerging status as an increasingly “elevated” and “respectable” art form. This was partly the knock-on effect of an early ’50s trend on the part of studios to trim budgets — jazz quintets generally worked cheaper than dedicated full-time studio orchestras — but it also coincided with a slow but noticeable shift in attitudes towards what subjects movies could dare to depict. (Some of the most morally contentious films from the postwar portion of the Hays Code era — Otto Preminger’s The Man With the Golden Arm (1955) and Anatomy of a Murder (1959), and Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1964), just so happened to have jazz scores — as did later flashpoints for controversy like Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris (1972) and Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976).) That shift meant regarding jazz not just as a subject of interest, but a component of a greater piece of work — not just as a way to make a film’s setting feel credibly hip, but as a way to engage with something more distinctly spontaneous and direct compared to the labored-over and carefully orchestrated symphonic works that typically drove film scores. And that gave rise to a curious effect: the feeling that an improvisational ensemble form of music could convey a further depth of unpredictability and you-are-there verite than any other form of music available to the otherwise carefully controlled and meticulously assembled mise-en-scène of the silver screen.

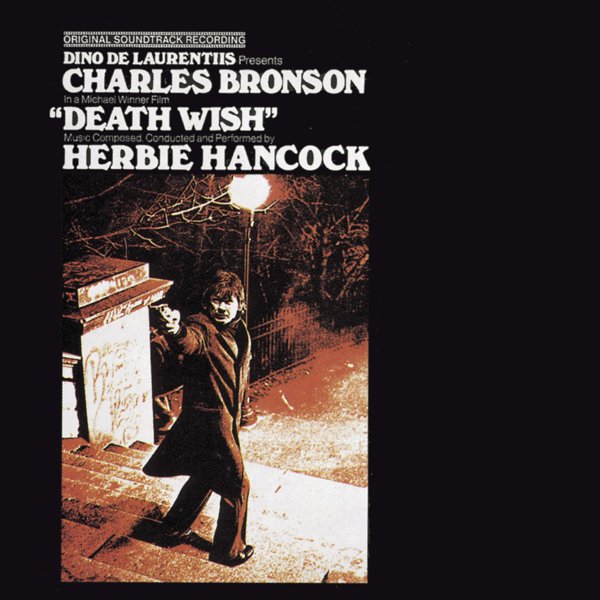

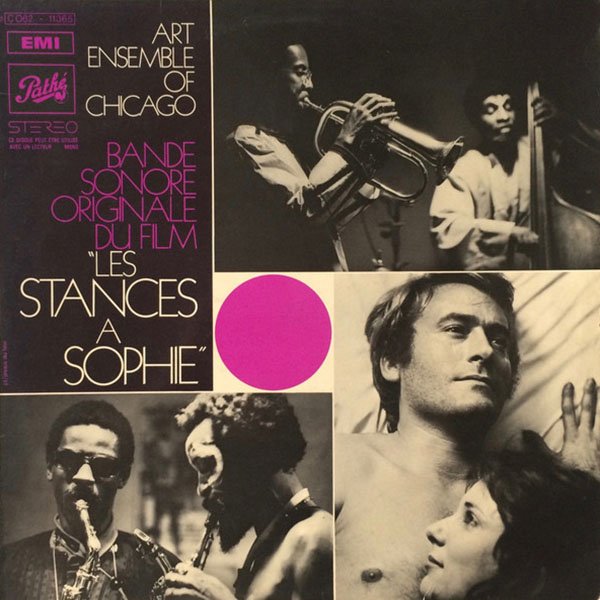

So while jazz on film would continue to be a popular subject in and of itself — think the nightclub-world confines that Frankie Machine haunts in The Man With the Golden Arm, or the prominence of the all-star combo that plays throughout the party that animates All Night Long — it would become almost inseparable from a succession of cinematic trends that brought each new development in jazz along for the ride. Film noir would find such a memorable expressive outlet through the presence of a jazz score that dark, fatalistic crime stories and sultry horn sections would, at least to future generations, seem inseparable to the point of total symbiosis. And as jazz evolved from bebop to newer forms, its role in film expanded accordingly: post-bop hybridization would develop alongside an arthouse movement that saw increasingly autonomous, studio-flouting European and American directors deconstruct the old tropes of Hollywood; free jazz would find purchase in the avant-garde wake of the New Wave; fusion would inject New Hollywood’s neo-noir stories of inner-city tension and corrupt power brokers with a careful balance of funky groundedness and glossy sophistication.

As “cinema jazz” is such a broad category, this guide’s operating under a few specific parameters of the definition. First, these films cover a roughly two-decade span, from the mid-1950s to the mid-late ’70s, where jazz was a major enough commercial genre and its presence didn’t seem like a statement on the relevance of jazz in itself. The films that gave us later works like Branford Marsalis and Terence Blanchard’s score to Spike Lee’s Mo’ Better Blues or Justin Hurwitz’s pieces for Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash approach jazz-as-subject from a different vantage point, as music that follows and struggles with its traditions (though, it should be emphasized, not to their detriment). This also goes for period pieces like Robert Altman’s Kansas City or Roman Polanski’s Chinatown — reiterations of jazz movements past, however exciting, that aimed to recreate sounds that history had already written the book on. Nonetheless, it remains a broad category that can lead you down any number of paths, and these albums all offer their own kinds of narrative immersion — whether or not there’s visuals, dialogue, or a three-act structure to drive it.

![3 Days of the Condor [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5660811997741056_600.jpg)

![The Man With the Golden Arm [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5695595448893440_600.jpg)

![The Cool World [Original Score] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/4634870206693376_v1_600.jpg)

![The Pink Panther [Music From the Film Score] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5749366925033472_v1_600.jpg)

![Taxi Driver [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5730059667111936_v1_600.jpg)

![Bullitt [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/6594174740594688_600.jpg)

![Alfie [Original Music from the Score] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5903249758486528_600.jpg)

![Anatomy of a Murder [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5789203984023552_600.jpg)

![$ [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/4876551856324608_600.jpg)