When the teenage writer and aspiring experimental musician Geoffrey Rushton attended a gig by one of his favorite bands, Throbbing Gristle, in 1980 and had a chance to meet that group’s Peter Christopherson, it would have been a bold soul to have claimed what was going to result over the next quarter century, even beyond their own almost as long-standing personal partnership. But as the twin axes of the freeflowing musical, artistic and performance entity Coil, Rushton, most commonly but not exclusively known by the name John Balance, often in later years Jhon or Jhonn Balance, and Christopherson proceeded to create a massive subcultural impact. Relying on their interest in a wide range of instrumentation and electronic experimentation, they oversaw a vast slew of releases, from singles through to multiple album sets to unique one-offs including perfumes and book releases, not to mention a variety of notable videos and short film efforts as well. David Keenan’s book England’s Hidden Reverse, about Coil and their sonic and aesthetic compatriots Nurse With Wound and Current 93, as well as Nick Soulsby’s interview collection Everything Keeps Dissolving: Conversations With Coil are a few key resources to help further understand this remarkable double act.

With Balance, especially given his role as lyricist and vocalist, the more public and forthright of the two on various fronts while Christopherson maintained a certain wry reserve, his own widely successful work as a designer, cover artist and video and commercial director helping provide the group a fierce independence, Coil’s music itself was described in many different ways, from psychedelia to industrial to rave to ambient to simply experimental or even folk music. But the truth of their range and goals, informed further via overt resistance to mainstream heteronormative standards of love and sex as well as homophobia in general, connecting further to Balance’s deep interest in occult and esoteric practices, renders the group even more impossible to pin down, pursuing their own evolving vision as they chose. They did not do so on their own: numerous further musicians were key performers and collaborators over the years, most notably (but far from solely) Stephen Thrower in the 1980s and early 1990s, Drew McDowall through the 1990s and Thighpaulsandra in the late 1990s and 2000s, while engineer/producer Danny Hyde was a central participant in many sessions and releases in turn throughout their existence.

Both Balance and Christopherson brought their own creative experiences to the collaboration; while the latter’s Throbbing Gristle work was increasingly well known by that point, Balance similarly had been creating recordings on his own and in collaboration with others via acts like Stabmental and Cultural Amnesia. Similarly their joint first efforts emerged in wider contexts, as both were initial participants in Psychic TV as well as the group Zos Kia, which also included what for years were their only live performances in 1983. Following their formally recorded debut with the How To Destroy Angels EP, the duo soon signed with the Some Bizzare label for their initial two albums, Scatology and Horse Rotorvator, the latter of which became a massively influential album in industrial music circles in particular, as did their harrowing reworking of “Tainted Love,” providing a flipside to Soft Cell’s synth-pop landmark in the wake of the continuing slaughter caused by AIDS and associated health care and governmental neglect. For the rest of the 1980s they regularly appeared on a wide variety of compilations and also began associations with filmmakers with both planned and released soundtracks for directors, most particularly Derek Jarman, as more singles and collaborations emerged, Balance’s regular appearances for years on work by Current 93 being especially notable.

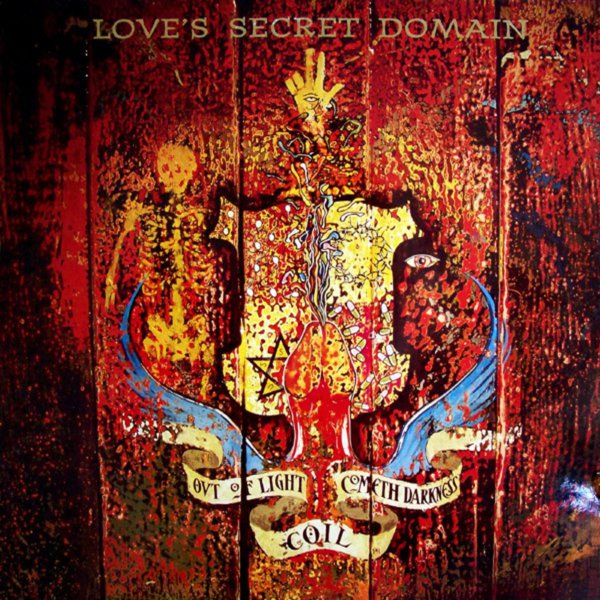

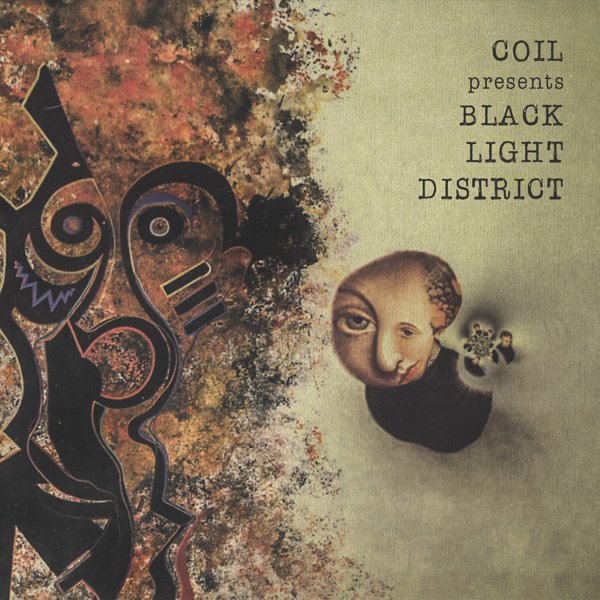

Having left Some Bizzare in 1987 to form what would be their own home label, Threshold House, Coil achieved a remarkable artistic next-level with 1991’s Love’s Secret Domain, incorporating the explosion in dance music interest in the UK with associated elements of hallucinogenic experimentation and their own multivaried inspirations. Both it and associated singles also were something of an American breakthrough thanks to its release on the famed Wax Trax label, while Trent Reznor, starting to come to wider attention with the success of Nine Inch Nails, commissioned some of the first remixes they did in 1992, leading to further remixing work for other artists that would continue until the group’s end, from Depeche Mode to Bill Laswell. Reznor also signed the band to his bespoke label Nothing for what would have been a planned album called Backwards; while demos and sessions were completed, however, nothing was formally finalized for release at the time. As an alternate creative outlet, the group released a variety of singles and albums under differing names such as ELpH, Black Light District and Time Machines, over time stepping further away from their dance-leaning early 1990s towards a more free-flowing drone and instrumental approach.

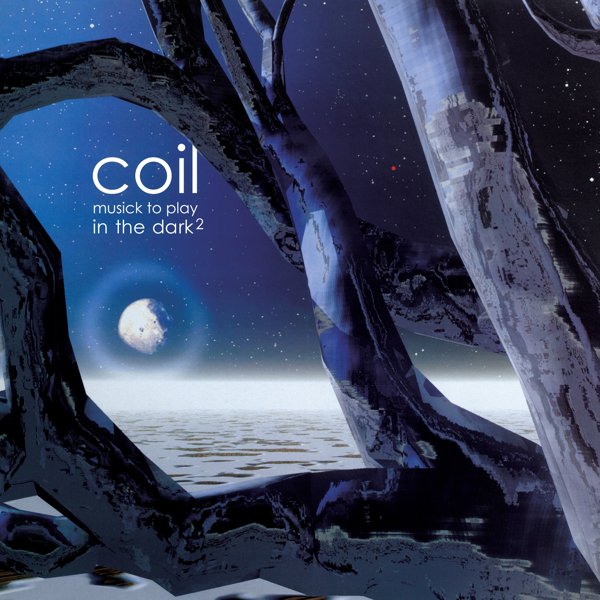

Building on this work, Coil’s next major phase encompassed two remarkable developments. The first was a full return to releasing work under the Coil name directly, including a seasonal EP series later collected as Moon’s Milk (In Four Phases) and another overall artistic triumph in particular, 1999’s Musick To Play In The Dark Vol. 1. These efforts were in part driven by their relocation from London to the UK countryside and its attendant slower and calmer atmosphere, as well as fully leaning into a turn from what they considered the masculine ‘black sun’ energy of their earliest days in favor of what they described as a more feminine ‘moon musick’ feeling. The resultant releases reflected their deepening interest in lengthier, often rhythmless constructions; at the same time, they also showcased some of their most enjoyable shorter compositions in turn, Balance’s voice now generally calmer and appearing less often than in earlier years. Late 1999 brought the other major change: Coil’s return to live performance, with a small collective of further guest musicians working with the band on a series of irregular shows around the world over the following years that aimed at being as visually surprising and memorable as their audio work. All of this led in turn to live albums emerging in time alongside continuing studio efforts such as The Remote Viewer and the more formal song efforts on Black Antlers. Christopherson also began participating in in a Throbbing Gristle reunion as Balance continued his many guest appearances with others; while their romantic partnership had ended by this point, they were on a true creative roll in the best of senses.

But what could have yet been a path to even more remarkable work by the two reached an awful conclusion. Over the years Balance had been increasingly open in public about alcohol abuse and its impact on him, with the multi-artist compilation Foxtrot in 1998 created as a fundraiser to assist him, containing a heartfelt, moving short essay from him on his struggle. In November 2004, following a bout of binge drinking, Balance fell from a balcony in his shared home with Christopherson, dying later that evening, only 42 years old. In the wake of the disaster, Christopherson moved to Thailand the following year, completing a final full posthumous Coil release, 2005’s The Ape of Naples, and otherwise spending subsequent years exploring new solo efforts and collaborations of his own, as well as continuing work in Throbbing Gristle and related efforts while planning and releasing more Coil archival projects in turn, including a notable DVD box set containing a number of their famed live performances, Colour Sound Oblivion. But sadly and no less tragically, Christopherson suddenly passed in his sleep in November 2010 at the age of 55, bringing the story of Coil’s key participants to a far-too-soon end.

Encompassing Coil’s full legacy requires much more discussion than can be provided by this guide – beyond their many studio efforts and live albums, during their existence they released three full CDs alone of various compilation and rarity appearances in their Unnatural History series, containing much crucial work. Meanwhile, their numerous 12” single and EP releases over their earliest years, themselves reissued and compiled at later points with even more rarities, adds considerably to their legacy. A welter of further reissues, releases of live concerts from their later years, presentations of yet more session work, collections of remixes for others, annotated download collections of yet more rarities and unreleased work and much more have created a truly chaotic grab bag of material that, unfortunately, has not all been given the thorough care and detailed attention it all truly deserves. To help provide a clearer grounding for the curious, with only a couple of exceptions this guide focuses on albums created and released when both Balance and Christopherson were part of this worldly sphere, the core work by which they achieved their continuing renown.