A decade and a half is a good run for any record label; not every imprint survives. But much like its slightly older but similarly short-lived Manchester compatriot Factory Records, by the time the London-founded and based Creation Records ended in 1999 it had, through a combination of circumstances and without any actual plan to do so, both commercially and subculturally impacted what rock music was on a worldwide basis, with effects still very much playing out to the present day. Creation was formed in 1983 by Alan McGee – the face of the label as much as Tony Wilson was for Factory – with his Biff Bang Pow! bandmates Dick Green and Television Personalities veteran Joe Foster also receiving shares (the latter was bought out in the late 1980s but would continue a regular association with the label). Creation was less driven by an exact sonic or aesthetic brief as it was by the idea of whatever sounded good at the time to McGee in particular, and as a result offerings either on the main label or its various affiliated sub-labels and spinoffs would range from bizarre sonic pranks to earnest tributes to earlier rock approaches to dance music experiments to much more besides. Given to self-mythologizing, and ultimately signing a few of the biggest self-mythologizers in music to boot, Creation wasn’t quite able to maintain itself in the end but the wild ride that resulted was more than enough of an experience.

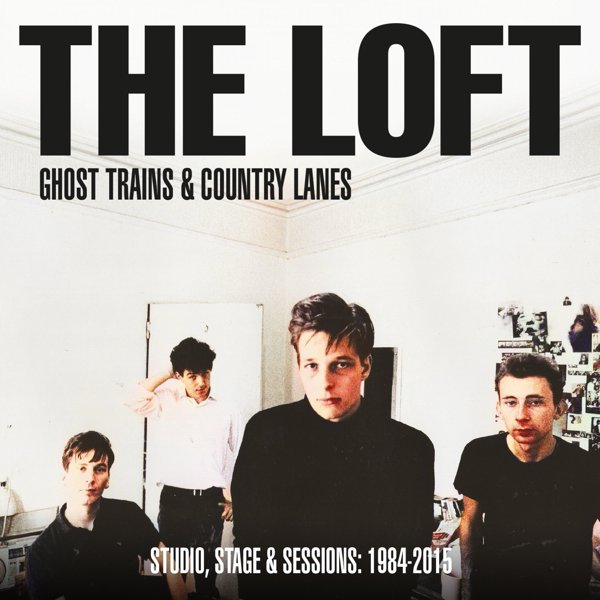

McGee was born in 1960 and raised in East Kilbride near Glasgow, making him a perfect age for punk rock to hit hard when it exploded in the UK in the late seventies, with McGee also noting the early efforts of Glasgow’s own punk-inspired acts like Simple Minds and labels like Postcard. He’d already met future Primal Scream founder Bobby Gillespie in school and their own first band experience, the Drains, was with another yet-to-be Primal Screamer, Andrew Innes. After he and Innes moved to London, McGee grew more involved in performing, fanzines and club bookings throughout the early 1980s. Specifically, he was a particular presence in an incipient indie pop/rock scene steering away from the gloss of commercially triumphant synth-pop in favor of a scrappier approach dedicated to DIY ideals, punk’s lingering impact and general obsessions with 60s pop and rock culture carried into a new decade. Labels like Cherry Red and él had already set this scene when Creation debuted with an initial single by The Legend!, the stage name of soon-to-be music journalist Jerry Thackray (aka Everett True), followed by various other efforts including Biff Bang Pow! and the earliest recordings by the Peter Astor-led The Loft. But it was the debut single, “Upside Down,” of a new band also from East Kilbride that Gillespie drummed for – the Jesus and Mary Chain – that brought fuller attention to McGee and Creation as a whole.

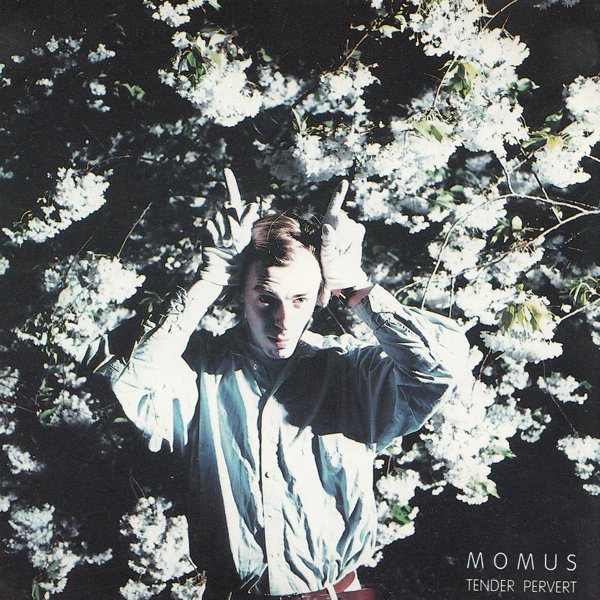

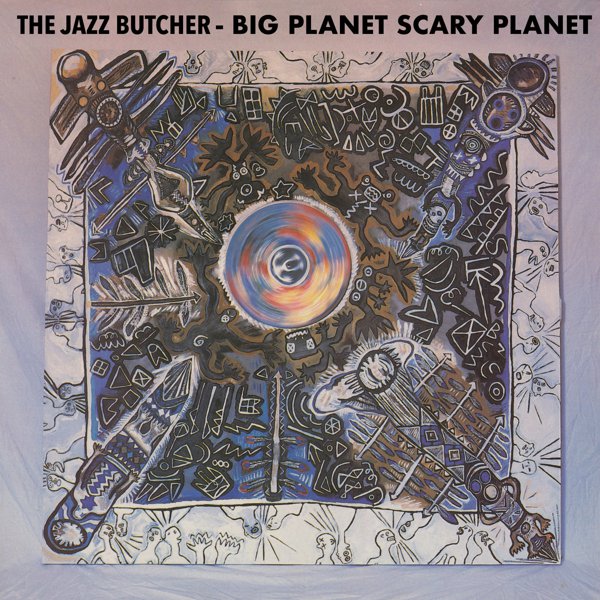

For the rest of the 1980s, McGee kept up a balancing act involving angling for press attention, searching constantly for money to keep things going, a resultant impact on his health and with time an increasing indulgence in drugs all while both running Creation and managing various bands including his own. As the label’s profile increased so did its roster, including such skew-whiff efforts as the bizarrely cynical Baby Amphetamine single, a droll solo album by future KLF leader Bill Drummond and the truly odd characters in Five Go Down To The Sea? But at the same time, an increasing number of acts from like-minded labels and scenes found a new home at Creation, including Felt, the Jazz Butcher, Momus, Foster’s fellow Television Personalities member Ed Ball in his incarnation as The Times, and Swell Maps founder Nikki Sudden via various solo and group projects. Gillespie had left the Jesus and Mary Chain to concentrate fully on Primal Scream, who signed to Creation, left for the majors and then soon returned to pursue their slightly fitful career as late 60s psych/protopunk fiends. Two other Creation acts, though, rapidly gained wider attention. The House of Love, whose remarkable singles and self-titled debut album made a big splash in indie rock circles, were notable enough, but when at an early 1988 Biff Bang Pow! gig McGee and Green caught the explosively loud and strangely pretty set of the opening act – a formerly Cramps/Jesus and Mary Chain obsessed band called My Bloody Valentine – both band and label’s fate were changed forever.

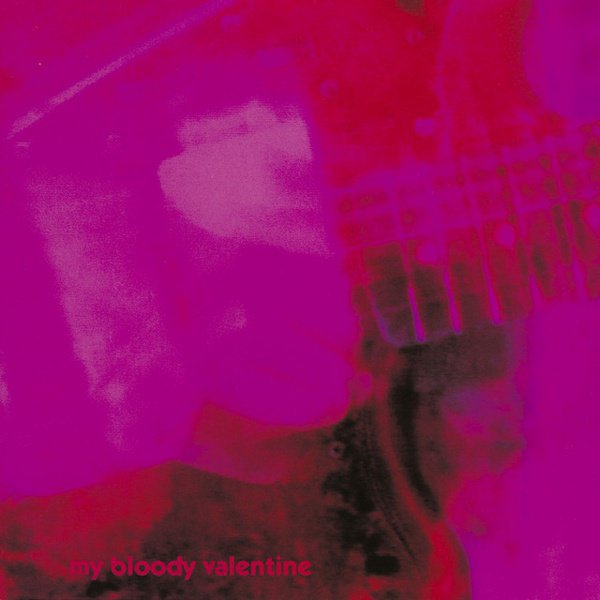

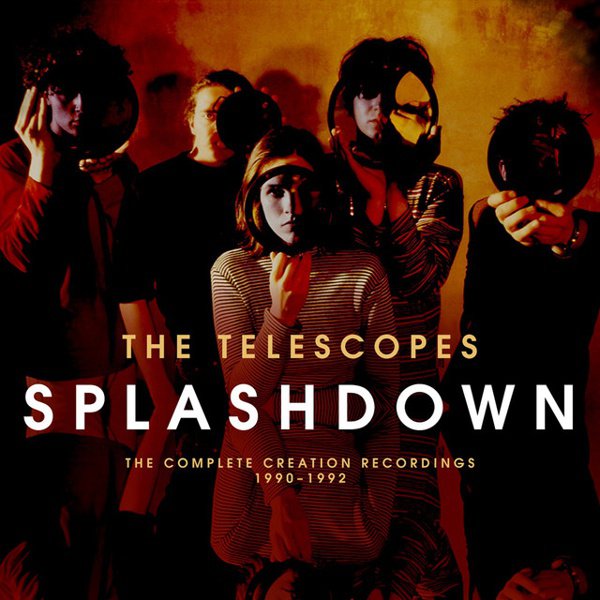

1990 proved to be a pivotal year for Creation, not least due to the release of My Bloody Valentine’s third EP for the label, Glider, leading off with a remarkable rock/dance fusion called “Soon.” That group’s impact had already begun to be felt by the label as a whole as numerous bands followed in their general wake, either by intent or by accident, with Ride, Slowdive and Swervedriver, and in the next couple of years the Boo Radleys and Adorable, all being seen as part of a new style that would receive the dismissive tag turned statement of purpose ‘shoegaze.’ But it was the transformation of a Primal Scream song by a wide-ranging music fan with an ear for the exploding dance/techno scene in the UK – a first-time remixer named Andy Weatherall – into the anthemic track “Loaded” that made an even bigger mark, with the eventual Screamadelica album turning Gillespie’s group into a major draw and setting the course for their future.

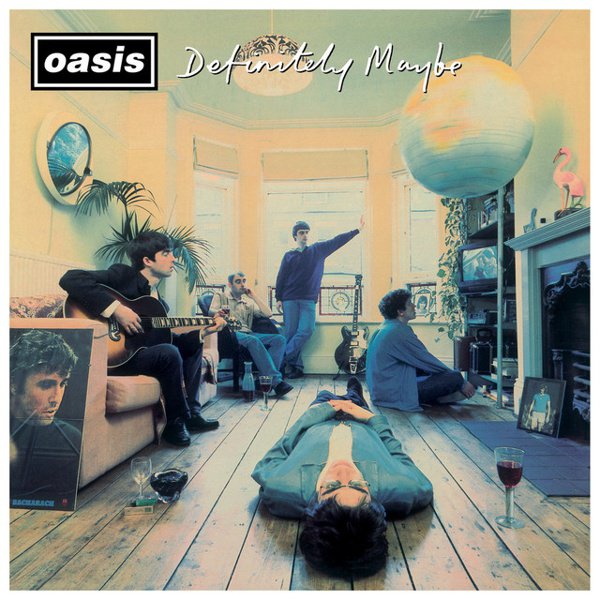

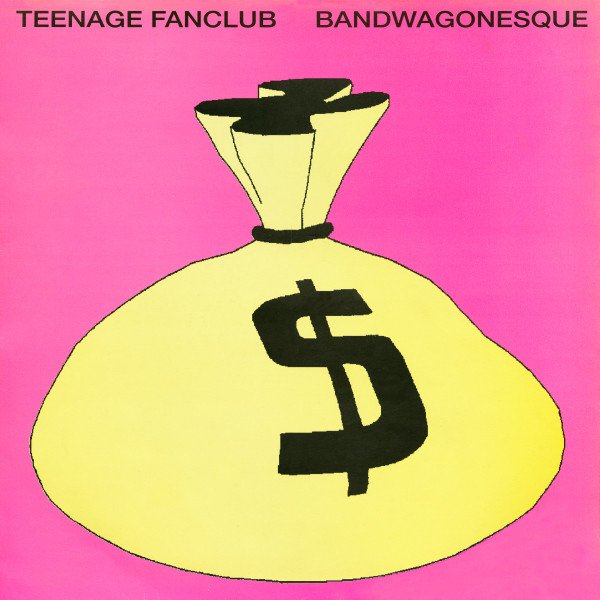

The early 90s also brought other notable signings including a newer Glasgow band, the engaging Teenage Fanclub, and two American acts in particular, the power-pop-crazed Velvet Crush and the Bob Mould-founded Sugar. Yet it was the ruinous recording costs of My Bloody Valentine’s second Creation album – the now-legendary 1991 release Loveless – which had the biggest impact all around, feeding into a cash crunch that led McGee and Green to decide to accept a buy-in from Sony Music to keep the label going. In the atmosphere of the early 1990s, as the success of Nirvana had shown in America, there was a new rush on the part of major labels in particular to see what could be done with indie labels and acts, so the business deal in and itself that wasn’t so remarkable – or wouldn’t’ve been if in May 1993 McGee hadn’t accidentally seen a Manchester band that had blagged its way onto a Glasgow-venue bill and immediately fallen in love with them. It was a tangled scenario given various preexisting US distribution deals but when all was said and done Oasis had signed to Sony worldwide, got licensed back to Creation in the UK and started releasing singles at a rapid pace.

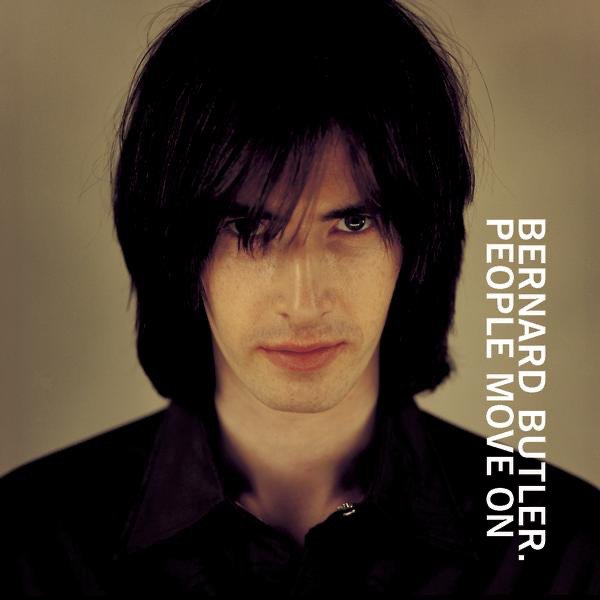

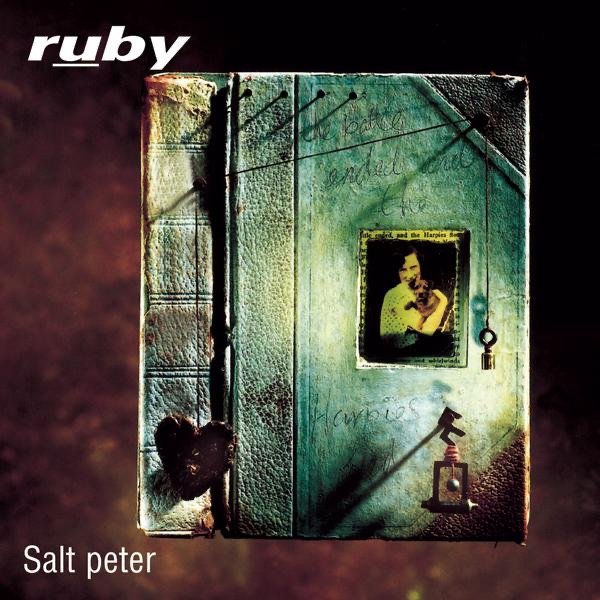

McGee himself had hit a drug-driven health wall in 1994 and took some time off to rehabilitate but the Oasis phenomenon fully kicked in then as well, eventually leading to the volcanic worldwide success of the 1995 album What’s The Story (Morning Glory)?, as of 2022 still one of the top five biggest selling albums in the UK ever. So singular and overwhelming was that triumph that the label, increasingly professionalized in feel and outlook as Sony got more involved in its doings, essentially couldn’t replicate it no matter what was tried. Some striking signings kept the label’s spirit going in different ways, including the stellar Welsh band Super Furry Animals and solo releases by Suede’s former guitar player Bernard Butler, as did the spirited work of Lesley Rankine, continuing on from the band Silverfish in a new project, Ruby. But a combination of Oasis wannabes and general Britpop hangers-on in a saturated market and atypical acts that failed to deliver – not to mention a sadly ignorant reaction to Dexys Midnight Runners leader Kevin Rowland’s genderfluid public image approach for his My Beauty album – left both McGee and Green increasingly frustrated with their business arrangement and ultimately led them to approach Sony to wind the label down in late 1999 so they could pursue new musical and artistic interests. The full story of Creation as told in books like David Cavanagh’s 2000 overview My Magpie Eyes Are Hungry For the Prize is well worth looking into, while other efforts like the 2021 film Creation Stories and McGee’s own knack for self-presentation means that the label’s story, from highs to lows, will yet be discussed for some while to come.