From Brazil’s saudade to the American blues and Ethiopia’s tizita, cultures worldwide have developed their own musical forms to express yearning, memory, and loss — feelings that transcend language. For the Tuareg, it’s assouf, a sound shaped by the struggle to preserve their heritage and the sorrow of a lost homeland.

Described as “the pain that is not physical,” the term assouf speaks to the emotional ache tied to loss — loss of land, freedom, and the nomadic way of life that once defined the Tuareg — and speaks to their history of exile and displacement, and their yearning for a time when life was closely connected to the land and the traditions that governed it. Better known as Desert Blues, assouf, like the American blues, transforms loss into art, soundtracking the Tuareg’s history of resistance and resilience.

The Tuareg, or Kel Tamashek, are a nomadic ethnic group that live scattered across the Sahara Desert and the Sahel regions of North and West Africa, divided between Mali, Niger, Algeria, Libya, and Burkina Faso. Traditional Tuareg music is marked by the steady pulse of the tinde drum, and the melodic tones of instruments such as the tehardent, a three-stringed lute, and the imzad, a single-string bowed violin, mostly played by women. As the music of a nomadic people, it’s close to impossible to pinpoint a precise origin, but the rhythms and pentatonic melodies are related to traditions from across the Sahel, and share common roots with a varied but connected lineage of sounds stretching from flamenco in Spain to string music in North Africa and the Levant.

Due to the shifting political landscape of their regions, the life of the Tuareg has changed radically during the 20th and 21st centuries. After the often violent eradication of French colonial rule in the early 20th century and the chaos that followed independence, the Tuareg found themselves spread across new national borders, often as minorities in countries like Mali, Niger, and Algeria. In constructing stronger, often Arab, national identities in these nascent countries, the Tuareg were often marginalized and discriminated against. Their struggles with new political orders led to multiple rebellions, which were met with violence and repression, forcing many Tuareg into exile. It was during the 1963 rebellion in Mali that a three-year-old Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, the future founder of desert blues pioneers Tinariwen, saw his father killed by the Malian Army. For Ag Alhabib and for countless others across the Sahara and Sahel, music became a crucial tool for expressing the pain of displacement, and a way to articulate their desire for freedom and their old ways of life.

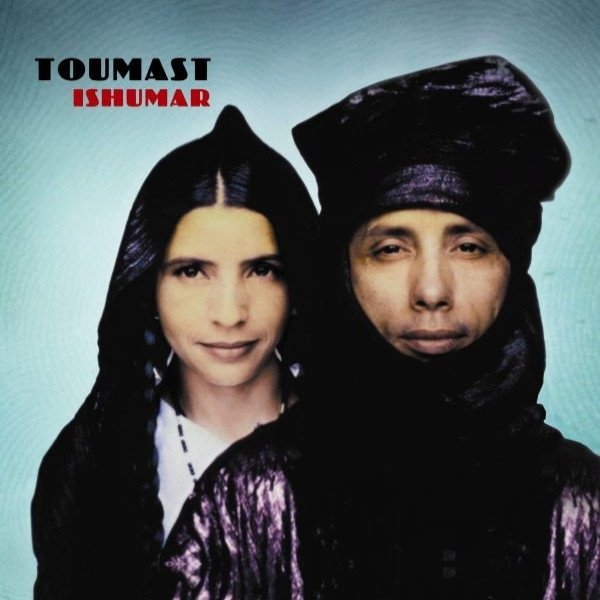

The countless young Tuareg men who were displaced in the late 1960s through the 1980s and began populating the cities soon became known as “ishumar,” a Tamashek corruption of the French word chômeur, meaning unemployed. The slur was reclaimed as a badge of honor, and the ishumar, whose ideas were being shaped by new experiences of travel, urban living, and work in sectors previously unfamiliar to Tuareg society, began envisioning a new independent Tuareg nation. The electric guitar, which was gaining popularity across West Africa, soon emerged as a symbol of political resistance and unity.

The modern, foreign instrument was particularly liberating for the Tuareg, as it allowed them to transcend the strict social norms of Tuareg society, which reserved specific instruments and songs for specific genders and social classes. Ishumar music was raw and deeply connected to the recent experiences of the Tuareg, while still being rooted in their tradition. It was a soundtrack for a generation of young Tuareg who were searching for meaning and purpose in a rapidly changing world.

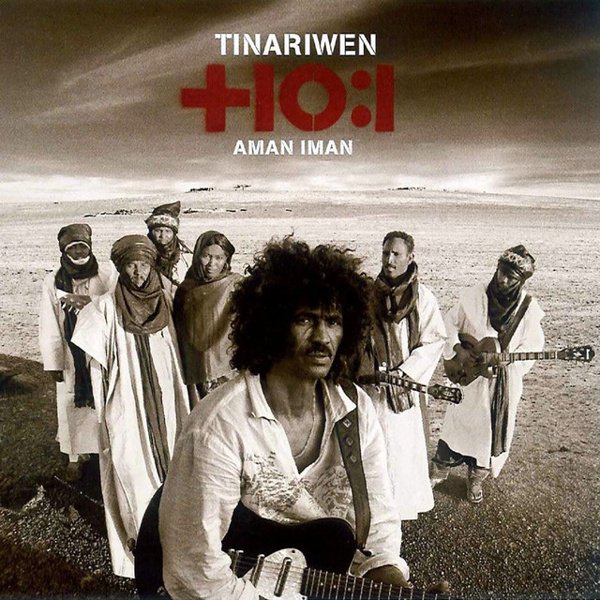

The story of Tinariwen, the first and most enduring Tuareg guitar group, is that of the ishumar. Years after witnessing his father’s death at the hands of the Malian army as a child, Tinariwen founder Ibrahim Ag Alhabib fled with other Tuareg exiles to Algeria, where he wandered between refugee camps working odd jobs. One day, or so the story goes, Ag Alhabib built his own guitar from an oil can, a stick, and bicycle brake wire after being inspired by a Western film, and began making music that drew from traditional Tuareg folk and Arabic pop, as well as from the guitar music of Santana and Dire Straits. Around this time, in the Tamanrasset region of Algeria, he met future bandmates Hassan Ag Touhami and Inteyeden Ag Ablil, and Tinwariwen’s idiosyncratic sound began taking shape.

Their musical journey was temporarily interrupted when in 1980, like many Tuareg men, they enlisted in the Libyan Army under Muammar al-Gaddafi, where they were exposed to Pan-African and revolutionary ideologies. When they came back together as a group their music took on a much more political tone, so much so that in 1989 their music, which traveled far and wide on pirated cassettes, was banned by the Malian government. The band soon became known as “Kel Tinariwen” or “The Desert Boys.” Their sustained, resonant guitar notes capture the vast expanse of the desert, while their repetitive riffs weave hypnotic soundscapes that, together with their sparse harmonics, conjure a sense of longing and resilience.

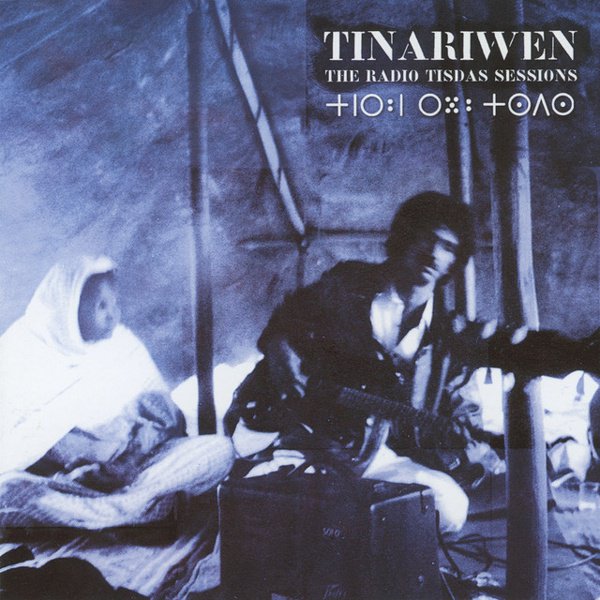

After decades of being well known amongst the Tuareg, in the 2000s Tinariwen’s music reached global audiences through their 2001 album The Radio Tisdas Sessions and the follow-up Amassakoul in 2004.

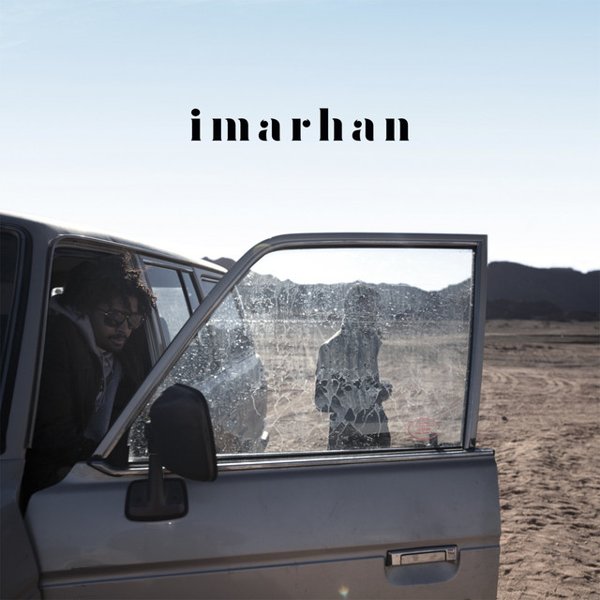

After almost a dozen albums, Tinariwen are still arguably at the helm of the desert blues sound, but their success has also paved the way for a new generation of Tuareg musicians. The likes of Niger’s Bombino, Mdou Moctar, and members of Imarahan all credit Tinariwen as foundational to their music. The fathers of desert blues have had an immeasurable influence on this new generation of musicians, and the desert blues sound is still defined by the long, flowing guitar lines and minimalist yet powerful riffing mastered by Tinariwen, and themes are still rooted in resistance, freedom, and exile — after all, the problems faced by the Tuareg have changed little over the past 50 years.

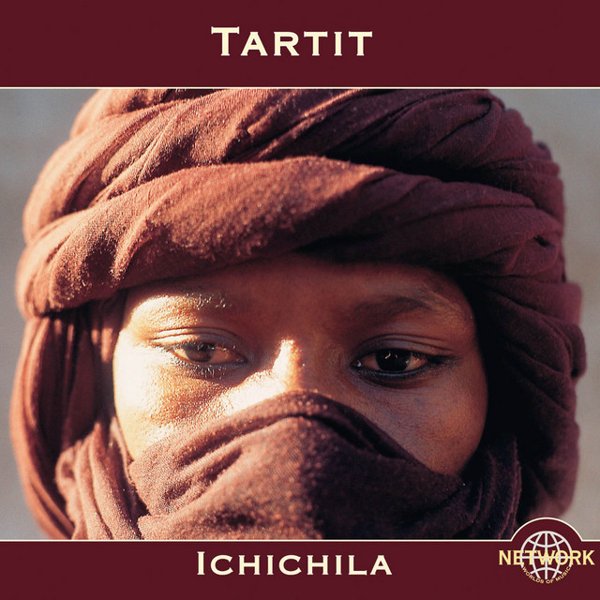

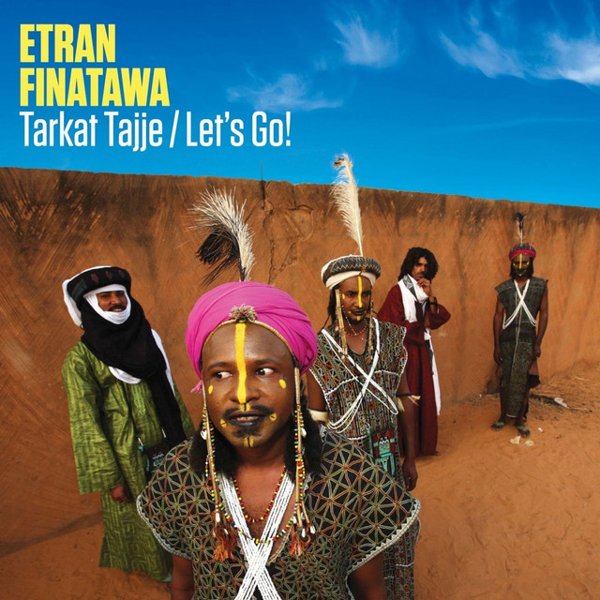

Yet artists are increasingly moving beyond the initial template, adding their own twist by adding electronic production, or in some cases returning to more traditional Tuareg sounds. Kel Assouf for example combine the rhythm of the tindé — the goatskin drum traditionally played by women — with modern elements, producing a unique sound that blends techno and Tuareg music. Imarhan craft a raw, more simple sound with a softer, less “rock” edge, while the mostly female group Tartit embrace the subdued sounds of the tehardent, creating a quieter, more traditional sound which places their vocals at the center.

![Zerzura [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5639964451143680_600.jpg)