Jazz has existed in the UK for around 100 years, with Dixieland jazz reaching British shores after World War 1. Throughout the continued development of the genre, the popularity and health of the UK jazz scene has ebbed and flowed, but the second half of the 2010s has been one of its most exciting and productive eras.

2018 was when UK jazz went overground, as musical shoots that had been quietly gestating over the preceding years bloomed into a series of brilliant albums from young, mostly London-based artists including Moses Boyd, Joe Armon-Jones, Sons of Kemet, Nubya Garcia and Kamaal Williams. And in the five years since, artists including Emma-Jean Thackray, Alfa Mist, Tenderlonious, Kokoroko, Ezra Collective, Nubiyan Twist, Ishmael Ensemble, Maisha and Blue Lab Beats have together produced an impressive collective body of exciting jazz and jazz-adjacent music, with a distinctively 21st-century British flavour.

The new UK sound includes plenty of straight-up jazz, but also an abundance of hybrid, fresh new takes on the genre, which drew on broader influences than the traditional jazz canon. This is jazz from a new generation of players who’ve absorbed the work of Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Charles Mingus, but who have also grown up in the UK’s multicultural cities where imported Afro-Caribbean musical traditions birthed new electronic genres like dubstep, grime, broken beat, UK funky and afrobeats. It’s jazz that can deftly incorporate elements of Ghanaian highlife, US house and hip-hop, or Jamaican reggae and dub, as well as UK club music with equal ease, and which is often aimed at or informed by what’s happening on the capital’s dance floors. This musical freedom, fluidity and interconnectedness was also reflected in the collaborative spirit of the new wave, with many of the musicians guesting on each other’s records and at live shows and club nights.

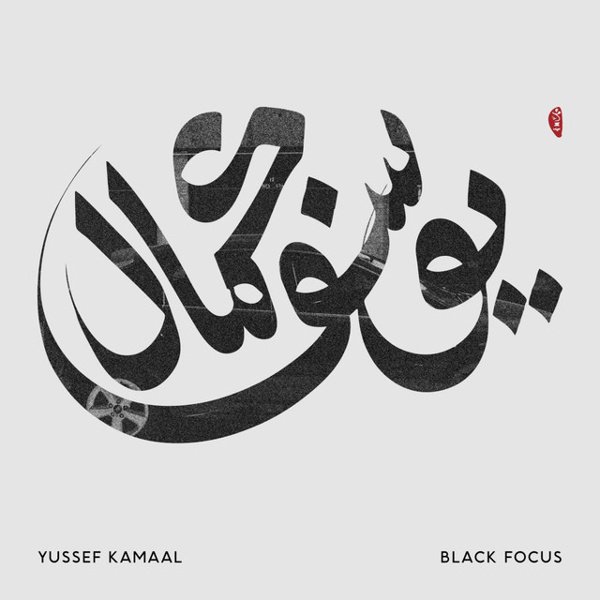

Yussef Kamaal’s (Keyboardist/producer Kamaal Williams and drummer Yussef Dayes) superb Black Focus album, issued in 2016, was an important moment for the new vanguard. Williams’ cosmic-jazz synth stylings and Dayes’ fiery breakbeats combined to create jazz that could work on dance floors as well as at dinner parties, and the album signalled the incoming surge of potent next-generation jazz that was just around the corner. However, it was, as is often the case with club/dance/electronic-related music, a compilation album that crystallised the UK jazz renaissance in the public eye.

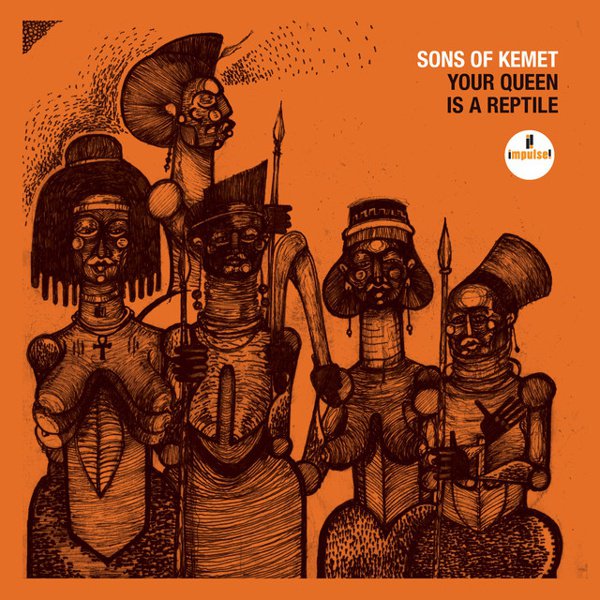

2018’s We Out Here was released on UK DJ and jazz-evangelist Gilles Peterson’s Brownswood label and was compiled by sax and clarinet player Shabaka Hutchings. Hutchings is something of a figurehead for the current UK jazz scene, leading two bands — Shabaka and the Ancestors and Sons of Kemet — and he’s also a member of psychedelic funk jazz band The Comet Is Coming. The album provided a convenient and accessible audio snapshot of an emergent young scene in all its varying glories, a growing, confident and creative musical community that was largely outside the mainstream industry. It also showcased an impressive breadth of stylistic invention and musical cross-pollination, with re-worked spiritual jazz, jazz funk, fusion and abstract improvisational jazz all given a brand new flavour via afrobeats, grime, hip hop and electronica.

While there is definitely a ‘scene,’ the UK jazz renaissance of the last five years includes an extremely broad range of musical styles, temperaments and aesthetics. The solo albums of keyboardist Joe Armon-Jones for example, who also plays in Ezra Collective, are dense, over-dubbed, electronic jazz-fusion, while Kokoroko specialise in afrobeat, highlife and funk-flavoured ensemble-jazz. Saxophonist Nubya Garcia’s jazz is rich with the music of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora, while Greg Foat makes jazz influenced by library music, ambient, psychedelia and folk. Blue Lab Beats happily trample through a number of genre boundaries, incorporating highlife, neo-soul, broken beat, hip hop as well as jazz into their music, and some of Moses Boyd’s tracks feel like grime instrumentals played in a jazz style while others are futurist jazz cross-pollinations that almost defy categorisation.

Five years into the renaissance and UK jazz is healthier than ever: young artists and bands are regularly appearing at major festivals and on radio and TV, they’re picking up nominations and awards and jazz is played by club DJs and remixed by dance music artists. Jazz in Britain is currently the most mainstream it has been for years and perhaps more importantly, it’s resonating with young listeners and clubbers, mainly because it’s being made by people who have shared dance floors with and listened to the same pirate radio stations as their audiences.

The last few years of UK jazz have produced a genuinely impressive catalogue of music characterised by invention and collaboration, a body of fresh, outward-looking, innovative, multicultural jazz, connected to what’s happening at street level in the clubs and plugged into various vibrant, creative UK dance, bass and electronic music scenes: dig the new breed.