The recorded Duke Ellington catalog is an intimidating place to contemplate from outside — though once in, nothing could be more inviting. As a musician whose five-decade career was bisected almost exactly by the shift from 78s to LPs (and 45s), Ellington cannot be summed up by albums alone. There are many Ellington overviews and box sets, and the best of them are to be explored for an extended time, at the listener’s leisure — each is, in itself, simply too rich not to roam around in for a while. No one collection does him full justice, and none ever will. That includes my own Spotify Ellington playlists: one of originals, another of core repertoire, often in multiple versions, and a third of live recordings. None are definitive — I’m a fan, not a scholar — and all teem with delectable music.

The Duke produced liturgical music and pseudo-jungle exotica, spiky modern trio dates and the most gossamer of mainstream ballads. He kept the best players around by letting them do their thing on- and off-stage, just as long as they kept the latter’s habits off the former’s hallowed ground; the Ellington Orchestra was don’t-ask-don’t-tell in the same way as the Grateful Dead. The Duke’s arrangements never stopped shifting and never stopped surprising, so when these road dogs had a night recorded or broadcast for later release, they often differed widely. Ellington and his second composer-arranger, Billy Strayhorn, exuded jaunty cosmopolitanism, even when praising the Lord in robes.

Born in 1899, Ellington grew up in Washington, D.C., and moved to New York by the early twenties, making a name for himself quickly as both a roguish charmer and a peerless pianist. The New York City historian Donald L. Miller wrote of Irving Mills, a Tin Pan Alley promoter, that Mills had “discovered Ellington playing at a basement dive called the Club Kentucky, a rowdy interracial club in the Broadway Theater District” in 1926. In December 1927, Ellington’s band moved uptown to the Cotton Club, where Black performers played for exclusively white audiences in Harlem, the capital of Black America. That era was defined by the innovative trumpeter James “Bubber” Miley, a pioneer of the “growling” plunger mute. He and the similarly growly trombonist Charlie Irvis were key to the “jungle music” motifs that, by necessity — it was in the club’s décor stage shows, infamously — became central to Ellington’s late-twenties compositions. He left the Cotton Club in 1931.

Throughout the thirties, Ellington’s work grew by lengths in sophistication. In 1939, three big hires shored things up even more — bassist Jimmy Blanton, barely out of his teens and ready to stalk big game with his mountainous low end; the tenor sax hero Ben Webster; and most importantly the composer-pianist Billy Strayhorn, Ellington’s coequal until his death until 1967. The same year he came aboard, Strayhorn contributed “Lush Life” to the band’s book and ensured himself immortality.

Ellington was as integral as Frank Sinatra in establishing the long-playing album as a creative and cultural force. Beginning in the early fifties, he began a series of ambitious long-players intended to reconfigure his earlier catalog — the idea then being that people wanted the song rather than a specific version of it — which led to a lot of re-recordings. Yet Ellington, and certainly his arrangements, never stood still — those re-recordings often have a pull of their own.

Take “Caravan,” from 1936, one of the Ellington band’s hardiest numbers. The main melody originated with Juan Tizol, who’d received twenty-five dollars for his input; Ellington wrote the bridge and arranged it, his usual working arrangement with his star trombonist, who also co-wrote “Perdido” and “Pyramid,” among others, for the band. (Irving Mills attached his name to the songwriting purely as business.) The original version (on The Duke: The Columbia Years compilation) swings as loose and sharp as anything of its era, and trumpeter Cootie Williams’ controlled explosive blat presages not just a lot of other musical effects to come in jazz but elsewhere — it reminds me of nothing so much as a 303 snarl on an acid house track.

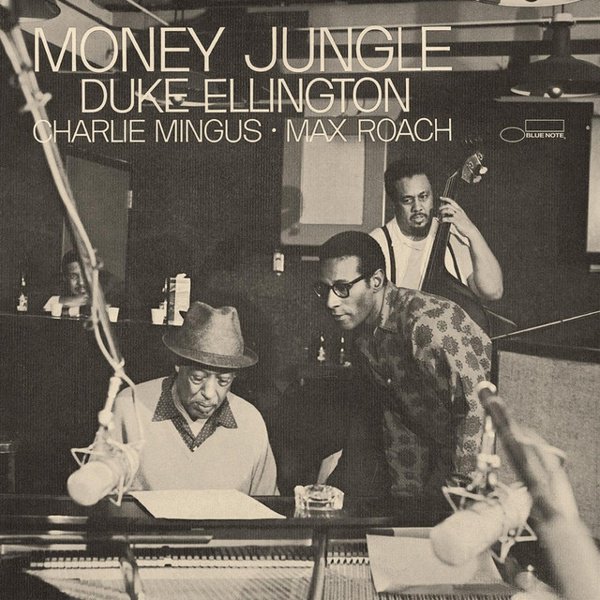

By 1946, though, they’re playing the song to a steadier, train-track rhythm, reflecting the rhythmic changes post-war, from big band swing to small-band propulsion, and phrasing the melody more mournfully. A 1955 version takes it even slower and more scenically, the tune taken up by deftly modulated brass. And twice in 1962, he laid the tune down in highly contrasting versions—first with a slower near-Mambo rather than the frisky original Latin tinge. It would come out a decade after Duke’s death, with Paul Gonsalves receiving a feature credit. Later in ’62, of course, Ellington would smash the keys down, disconcertingly hard, on one of his most beloved tunes as part of the Money Jungle session with bassist Charles Mingus and Max Roach, modernizing it with near-malicious glee. Then, in March of 1964, he played the song onstage in Stockholm — ten songs were issued in 1985 as Harlem — reconceived as a concert piece, its arrangement constantly shifting rather than concentrating on the melody. The ending even Dixielands it up a bit. Each version is highly distinctive, and that’s just one song.

Because Ellington so often re-recorded his material, he siphoned off new compositions to private recording sessions, paid for by himself, just to stockpile material. (There are ten volumes of The Private Collection, and this likely includes many other posthumous studio releases.) Often albums would be finished years before their release, and not just for posthumous releases. All the way back in 1945, Ellington and Strayhorn had labored over the recording of the four-part, eleven minute “Perfume Suite,” only for his label, Victor, to delay its issue until 1952.

You’d expect this guy to run out of gas at some point, and for many critics it was in the late forties, when the Orchestra had to adjust to the change in taste among black audiences for smaller groups. Yet not only did the Ellington Orchestra persevere — often to the detriment of its own finances — it thrived, winning a major comeback at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1956, its five-song condensing on LP a major bestseller. But Ellington challenged himself to the end. Strayhorn died in 1967, seven years before Duke, and their last album together, Far East Suite, is a complete triumph. And he had a serious late-life bumper crop, with the triad of Latin American Suite (1968-70), New Orleans Suite (1970), and best of all, The Afro-Eurasian Eclipse (1971).