Elvis Presley’s art is hard to get a grip on. The impact his earliest records — the fusillade of singles released between 1954 and 1956 — had upon American, and ultimately global, pop culture will never be equaled. More than 60 years later, it’s easier to place his music in its proper context alongside the work of Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis and others and see what each contributed to the invention of rock ’n’ roll, but at the time he towered over the world. There was Elvis, and there was everyone else.

It couldn’t last, of course. In 1958, he was drafted into the Army, where he served his full two years. Upon his return, he released one good album (1960’s Elvis Is Back!), but quickly embarked on a mostly awful string of uninspired soundtracks to embarrassing movies. By late 1967, the hits had dried up and Presley seemed woefully out of touch, yesterday’s man.

Everything changed in December 1968, when a one-hour TV special resuscitated his career and his artistic reputation. There were a few showbizzy production numbers and a gooey ballad of a single (“If I Can Dream”), but all anyone remembers today are the segments where Elvis and a small band including his 1950s compatriots, guitarist Scotty Moore and drummer DJ Fontana, sing blues and early rock ’n’ roll songs and tell jokes, with Presley wearing a skin-tight black leather suit and delivering the most committed, swaggering performances anyone had seen from him in a decade.

The TV special was a massive hit, and Elvis realized exactly how big a second chance he’d been given. He entered American Sound Studio with producer Chips Moman in January and February 1969, and cut his first non-soundtrack album since 1962’s Pot Luck. From Elvis In Memphis was released in June 1969, and in many ways it marked the debut of Elvis Presley, album artist. Unlike most of his earlier releases, which threw together a couple of rock songs, a couple of soppy ballads, and a take on whatever was popular at the moment (a 1961 album was literally called Something For Everybody), From Elvis In Memphis featured taut country-soul arrangements that served the songs rather than making craven attempts to chart, and Presley’s vocals were delivered with more passion and craft than he’d shown in years.

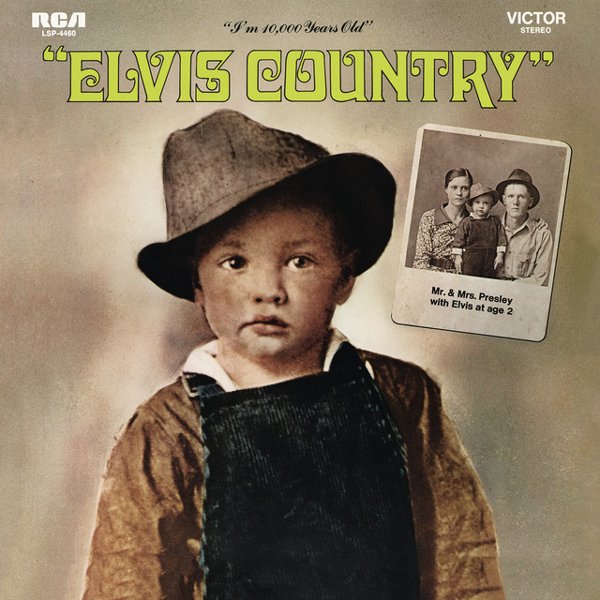

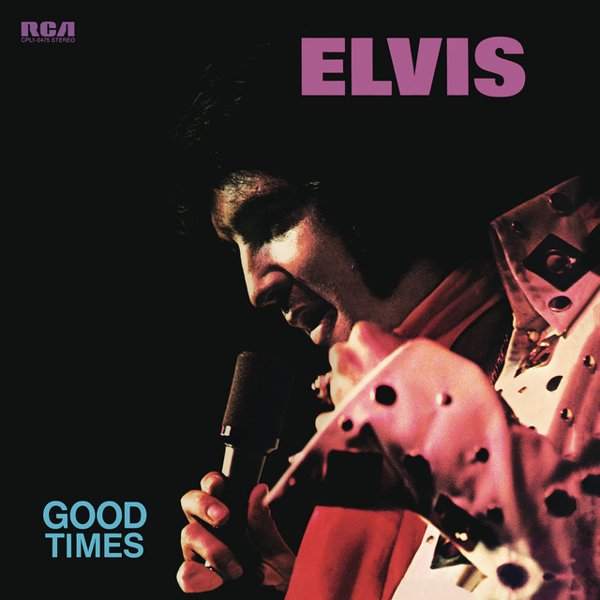

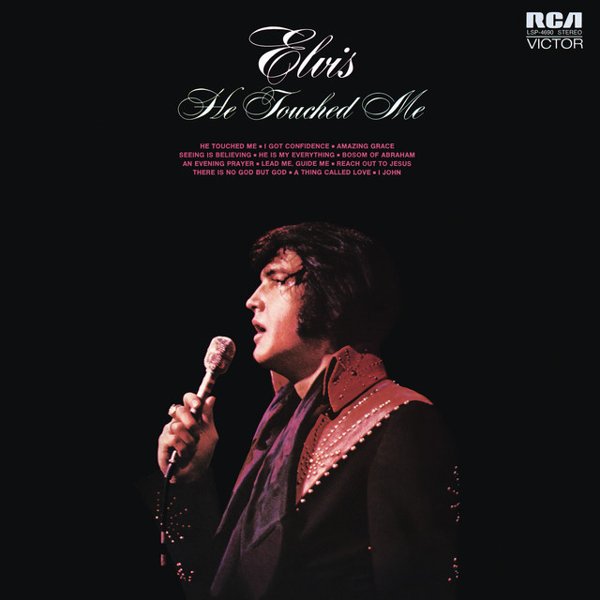

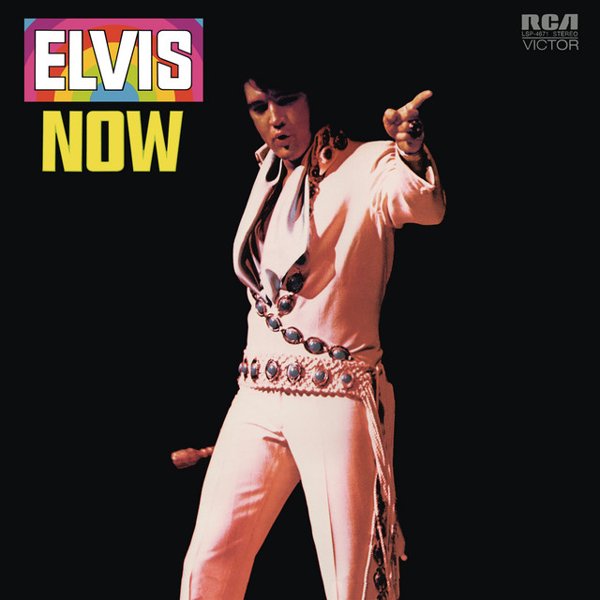

Between 1969 and his death in 1977, Elvis threw himself into his music like he hadn’t done since the ’50s, and the results were…well, a mixed bag. While he was a thrilling rock ’n’ roller, a convincing country and blues singer, and maybe one of the greatest white gospel performers ever, he had a cheesy side, and would quite happily sing hammy ballads that even crooners like Dean Martin and Johnny Mathis might have turned up their noses at. But the show tunes were kept to a minimum on his 1970s albums, and balanced by work from forward-looking singer-songwriters from the folk-rock and country realms. Elvis recorded songs by Kris Kristofferson, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Gordon Lightfoot, Bob Dylan, and the Beatles, and transformed a latter-day Chuck Berry song, “Promised Land,” delivering a breathless country-rock performance. He also emphasized different parts of his unique version of American music in different years — while he focused on country-tinged material in 1971 and 1972, in 1973 he recorded at Stax Studio and emerged with three deeply soulful, even funky albums.

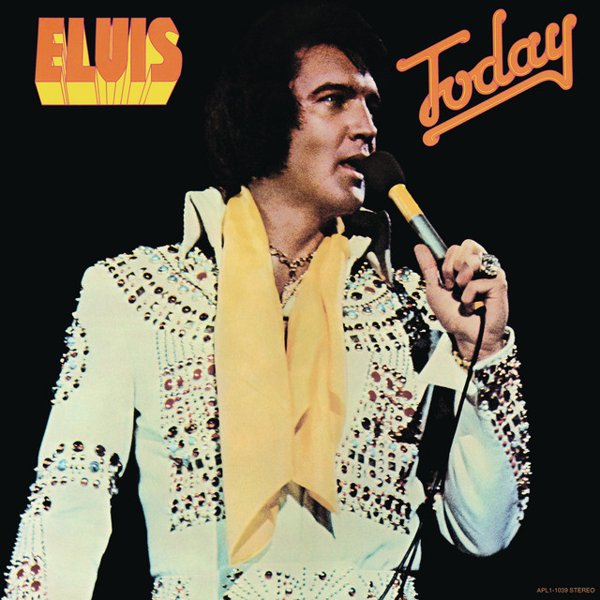

As weird as it sounds, Elvis also blossomed as a live performer in the Seventies. After performing in Las Vegas in 1970, he began touring the US extensively — he played 168 concerts in 1973. Backed by an explosive band that included lead guitarist James Burton, bassist Jerry Scheff, and drummer Ronnie Tutt, he delivered a mix of new songs and oldies, telling jokes and goofing around with the audience. Live albums from the era, and films like Elvis: That’s The Way It Is and Elvis On Tour, documented a rejuvenated Presley doing what he did best and seemingly both happy and artistically fulfilled.

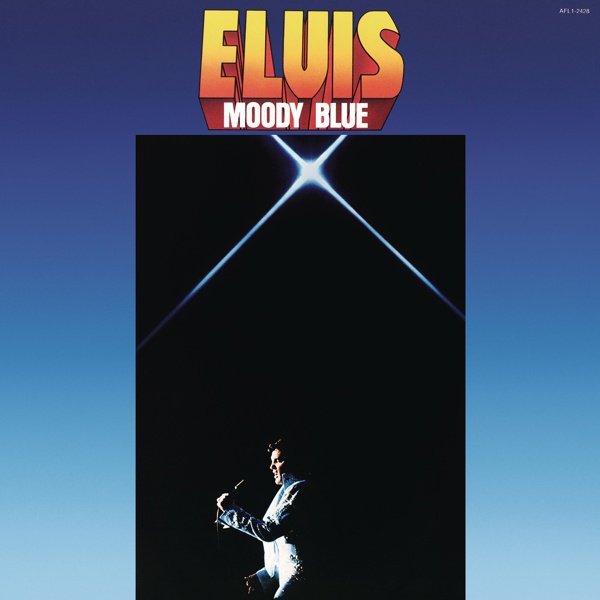

Of course, that wasn’t the whole story by a long shot — Elvis Presley was a man with demons and addictions, and they destroyed him in the end. And in the decades since his death, his cultural status has been debated, litigated, condemned and defended in a seemingly never-ending cycle that rarely seems to take the actual man (who, at a press conference announcing his first Las Vegas residency, pointed to Fats Domino in the audience and said, “That’s the real king of rock ’n’ roll, right there”) into account. But taken purely as music, his Seventies studio albums are the work of a brilliant interpreter who knew what he wanted and knew how to get it. The many outtakes available on various boxed sets and compilations document him conducting the band, joking with backup singers, and keeping things loose and fun, all while pursuing a creative result with relentlessness and determination. Far from a spent force, Elvis did much of his best work in his final decade.