Latin boogaloo owes its invention to a familiar progenitor of creativity: a generation gap. By the mid-‘60s in New York City, a young cadre of singers and musicians were hungry to stake a claim in the city’s competitive Latin music scene. Many were still teenagers who had grown up listening to the mambo machinations of giants like the “Two Titos” — Puente and Rodriguez — but they were also fans of doo-wop and R&B, dreaming of becoming the next Frankie Valli. It’s at this intersection, between Afro-Cuban rhythms and American soul, that boogaloo emerged as a compelling crossover style for the younger cohort to call their own.

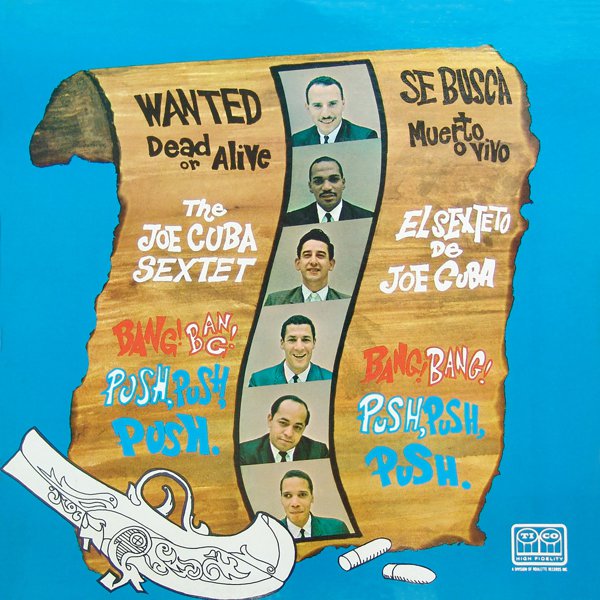

As a musical term, “boogaloo” first arose in 1965 to refer to a dance style popularized by R&B recordings like Tom and Jerrio’s hit single “Boo-Ga-Loo,” though debates still rage about what came first: the boogaloo dance or the boogaloo song. Regardless, its “Latinfication” followed in 1966 as New York musicians began to tinker with combining the infectious rhythms of Afro-Cuban dance styles like guajira and guaguanco with backbeats and basslines inspired by the latest R&B hits. That combination proved irresistible, first to the multi-racial audiences who flocked to dance halls where artists like Pete Rodriguez and the Joe Cuba Sextet performed. Radio play further amplified the style’s reach and popularity, especially as most boogaloo songs were performed in English rather than en español. Boogaloo may never have attained the popularity of rock n’ roll or hip-hop but all three share similar roots as products of cross-cultural encounters and exchanges that brought together multiple communities of listeners and fans.

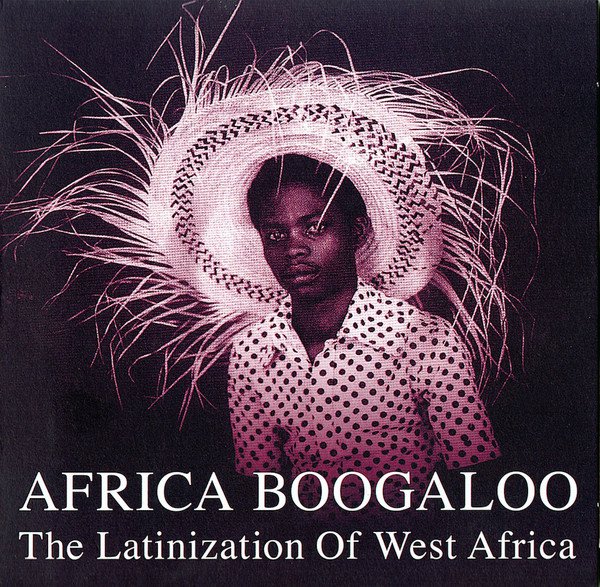

It’s hard to overstate boogaloo’s popularity, not just in New York but globally. Recordings quickly sprouted up in countries like Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela. Boogaloo even made it over to West Africa, as musicians from Senegal down to Guinea recorded their own takes on the style in their native languages, bringing the Afro-Cuban influences in boogaloo back to their cultural origins.

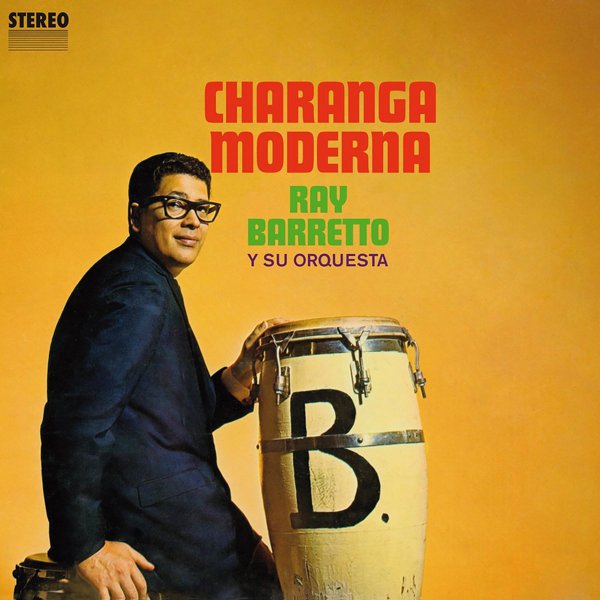

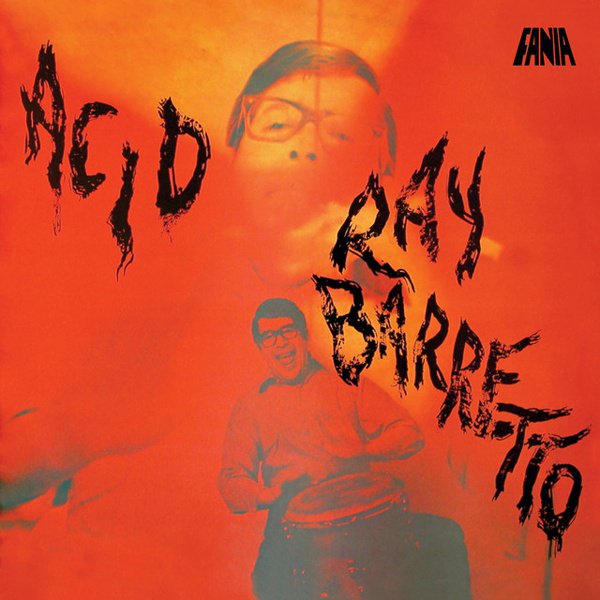

Even older musicians, many of whom initially dismissed boogaloo as a dumbed-down version of the Latin music they held to be more “pure,” found it difficult to avoid the trend if they wanted to stay relevant on radio and record charts. Much like how, a decade later, skeptical soul music artists would dabble in disco as an act of career survival, some of boogaloo’s more vocal detractors, including Eddie Palmieri and Larry Harlow, would eventually record memorable boogaloo tracks, however ambivalently.

The backlash against boogaloo by the Latin music establishment may explain why its lifespan was relatively brief, between 1966 and 1969. Yet even in that short span, it helped launch long careers for the likes of Joe Bataan, Ricardo Ray, Bobby Marin, Louis Ramirez, and Willie Colón. But for most others, such as Johnny Colon, Pete Rodriguez, and Monguito Santamaría, their recording output didn’t last far beyond boogaloo’s demise, especially once the salsa movement was in full swing by the early ‘70s.

Regardless, boogaloo’s continued influence is still resonant in 21st century pop music, whether in songs like Cardi B’s “I Like It” which directly samples from Rodriguez’s hit “I Like It Like That,” or in modern boogaloo records cut by groups like New York’s Spanglish Fly or Los Angeles’s Boogaloo Assassins. Given that it was always, at its heart, dance music, its ability to transcend the decades isn’t a mystery: so long as people are inspired to cut a rug to its rhythms, the boogaloo will live on.