Most discussions of Rainford Hugh Perry (a.k.a. Lee “Scratch” Perry, 1936-2021) proceed from the foundational assumption that he was certifiably crazy. The stories are legion, and are mostly pretty well documented: accounts of Perry in the studio praying to bananas, or drinking gasoline, or claiming to be a space alien, or explaining that he was able to create such dense and complex mixes using a crappy 4-track TEAC tape machine because although there were only four tracks on the machine, he was getting twenty additional tracks “from the extraterrestrial squad.”

And make no mistake, Perry loved to play up his reputation. Pictures of him later in life invariably portray a tiny, wizened old man with hair dyed bright red, wearing clothing and accessories that look like they were fashioned from random items found in a junkyard. His solo work features songs with titles like “I Am a Madman” and “Secret Laboratory.”

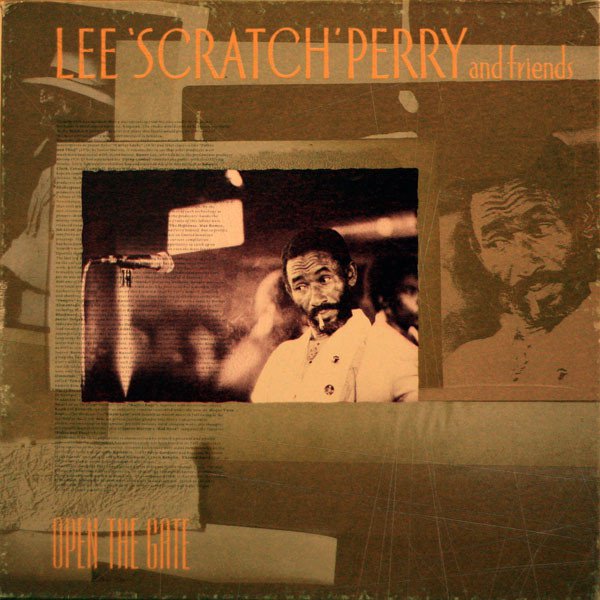

But weirdness is not the defining feature of Lee Perry’s life or career. Perry was a genuine musical genius, one of very few reggae producers who managed to create a sound that was completely and immediately recognizable as his own, and under whose tutelage artists like the Heptones, Gregory Isaacs, Max Romeo, and even Bob Marley and the Wailers made some of their best records.

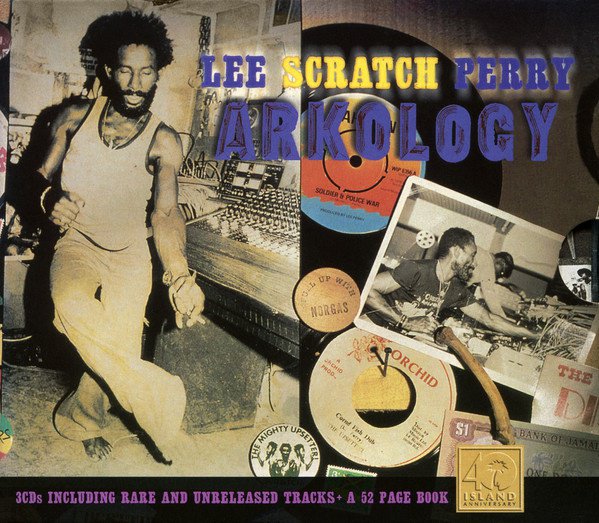

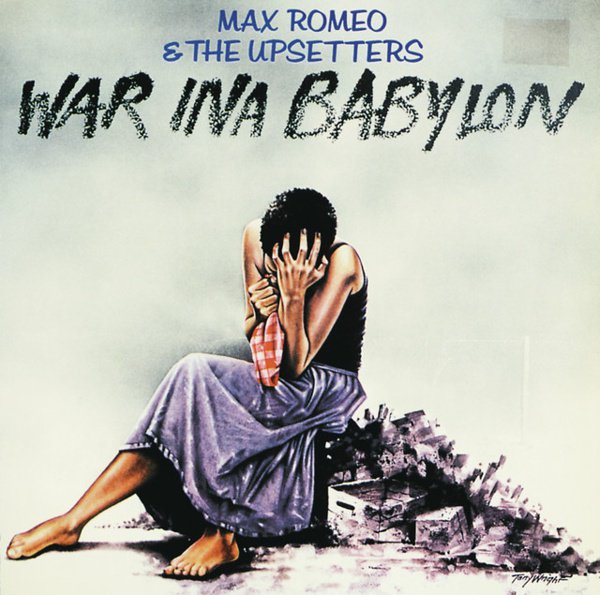

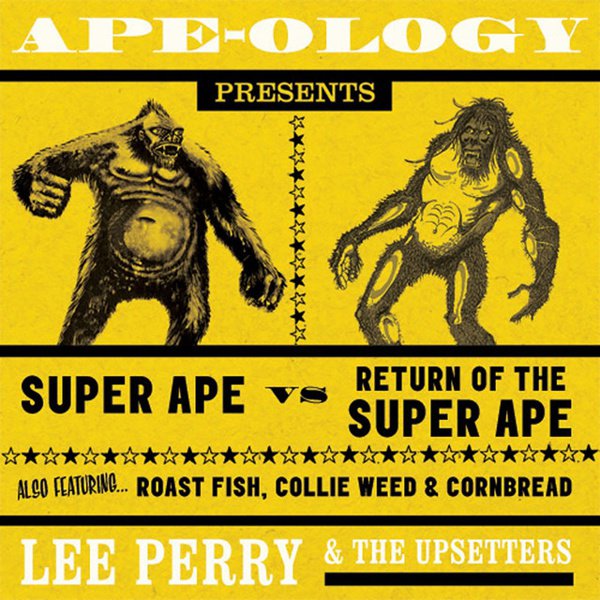

Perry got his start working in the famed Studio One under the supervision of Clement “Coxsone” Dodd, in the 1950s. Later he jumped ship and joined up with Joe Gibbs at Almagamated Records, but by the early 1970s he was ready to move out on his own. He put together a studio band called the Upsetters and made a string of excellent rock steady and early reggae albums with them, many of them consisting largely of instrumental tracks. In 1973 he built a small studio, which he called the Black Ark, and there he crafted a sound that was entirely distinctive: wet, splashy, and dark, characterized by heavy echo and reverb and odd sound effects. Perry didn’t invent dub (the art of radically remixing reggae tracks, dropping voices and instruments into and out of the mix), but he took it to places that not even adventurous colleagues like Augustus Pablo and the mighty King Tubby had thought of. And his production techniques tended to deepen and intensify the moods and flavors that were already inherent in the work of artists he produced: listen to albums like Max Romeo’s War ina Babylon and, perhaps most notably, the Congos’ Heart of the Congos and you hear Perry amplifying their roots-and-culture messages and dread worldviews through sound in a way that no other producer of the time could have done.

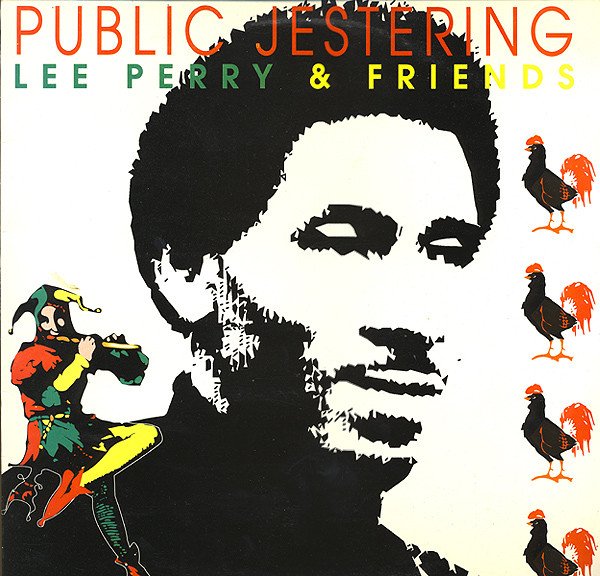

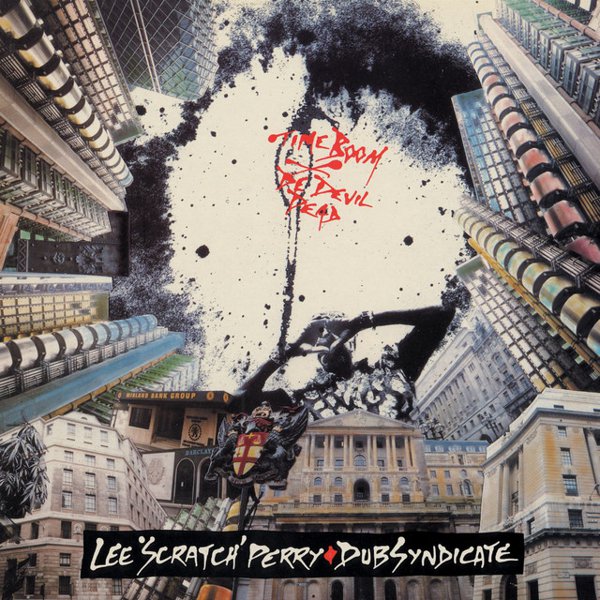

Ten years after building the Black Ark, Perry seems to have had a mental breakdown; the studio burned, and it’s generally believed that Perry himself torched the studio in an effort to expunge it of bad energy. His career then plateaued. No longer particularly concerned with producing others’ work, he made a long string of solo albums on which he mostly declaimed bizarre and often scatological lyrics over rhythm tracks assembled by his admirers. Some marvelous music was made during this long latter period of his career, especially with the brilliant producer Adrian Sherwood (of On-U Sound Records) and his house band Dub Syndicate, and then later with London-based Danny Boyle. He made some genuinely terrible music as well. (Some of the best and also some of the worst music he recorded in his later career was made at Ariwa Studios with Mad Professor.) But Perry’s real legacy remains the music he made while leading the Upsetters and, especially, behind the board in the cramped control room of the Black Ark. Those singles and albums remain among the most distinctive and impressive releases of reggae’s golden period in the 1970s.