If you want to dig into the curious nature of record collecting and sample culture as a resurrector of long-forgotten ephemera, a good place to start would be the surprisingly vast world of library music. With the explosion in popularity of television after WWII, library music — also known as production music or stock music — became a major concern, an easy way for the increasingly mass-market worlds of radio, film, and TV production to license pre-made songs without having to go through the trouble and expense of commissioning an original score. Its work-for-hire nature — cutting composers out of the licensing process, and typically leaving them anonymous and uncredited in the media their music appeared in — was offset by the ridiculously prolific nature of many of these composers, many of whom turned out pieces by the hundreds over the course of a decade or so. Some of them even broke through to a little sliver of mainstream recognition — think Alan Hawkshaw, whose production-house gigs helped spawn a cult hit and legendary hip-hop break with the Mohawks’ organ-driven funk vamp “The Champ” — but for the most part, fame for these artists was far from the point.

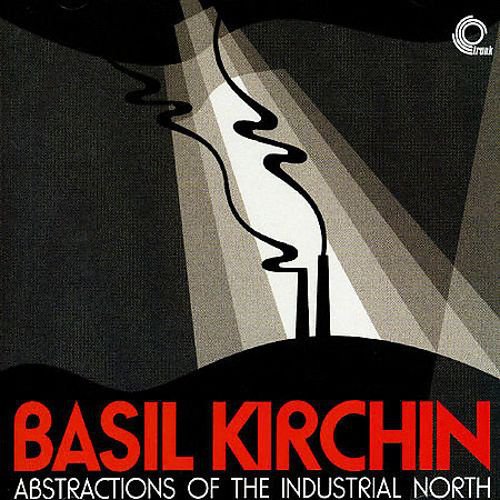

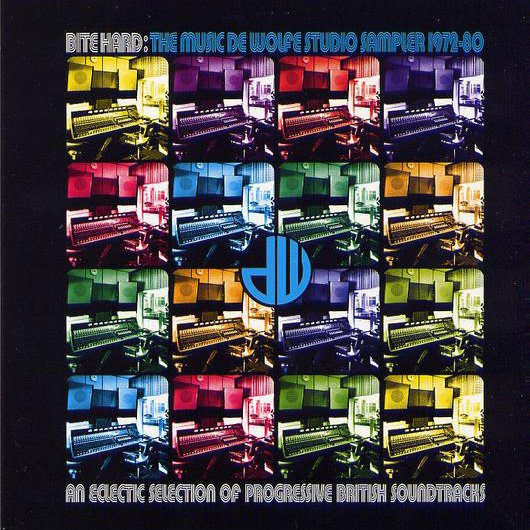

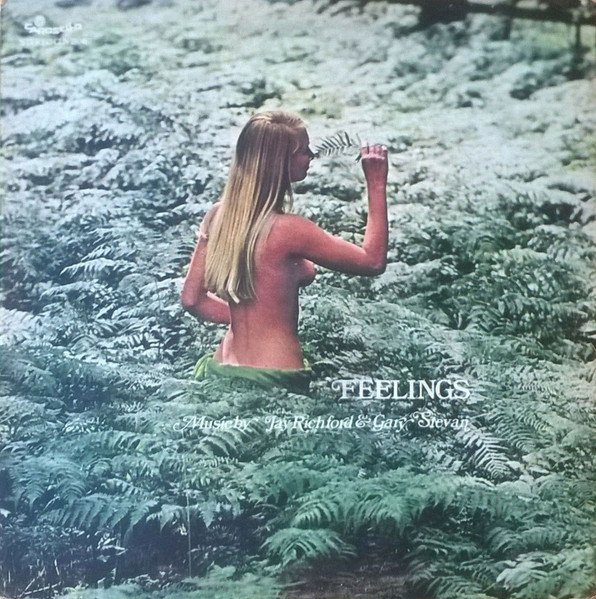

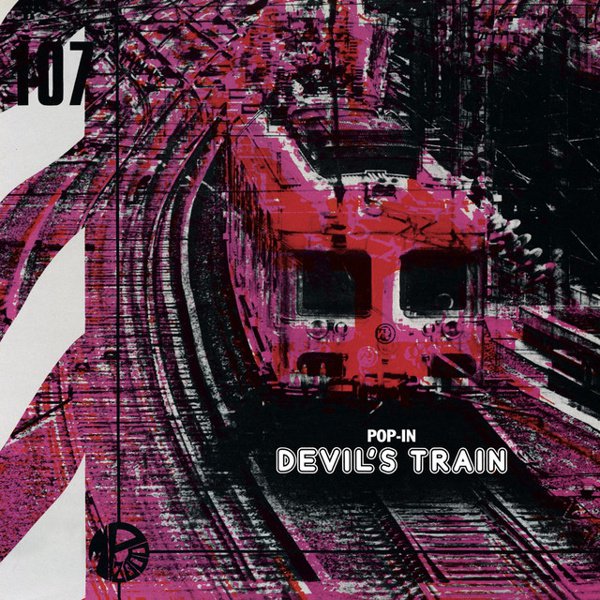

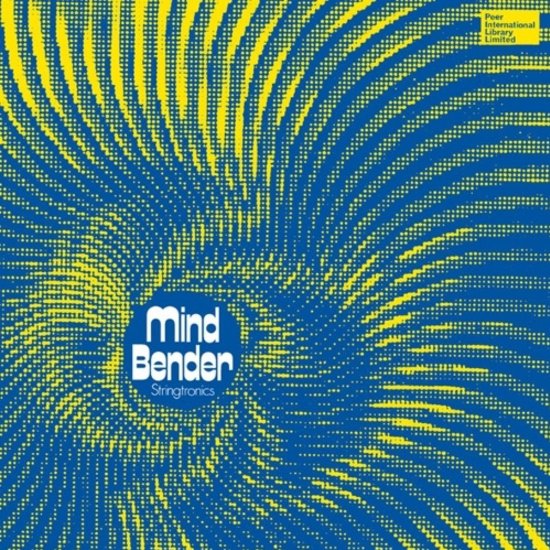

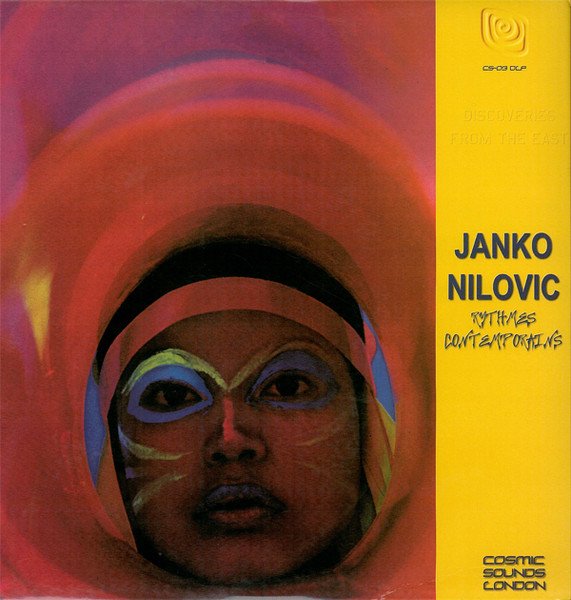

While it’s an international practice that still runs well into contemporary times, much of what people think of when the term “library music” comes up is a particular time and place: European and British, the mid ’60s through sometime in the ’80s, leaning primarily towards the jazz-funk side of the soundtrack equation, and cut for labels like Music De Wolfe, KPM, and Editions Montparnasse 2000. That particular milieu is still in popular use: TV series like How To With John Wilson and web documentaries such as the ones produced for SBNation’s sports-deep-dive series Dorktown use vintage library music to give their presentations a particularly distinct kitschy-yet-sincere feel, highlighting the weirdness of their subjects while emphasizing a sense of curiosity and enthusiasm. Another, of course, is in hip-hop and other sample-based music, a side effect of increasingly costly sample-clearance fees and rarity-arms-race cratedigger one-upsmanship. (KPM alone has become nearly as indispensable to a producer’s arsenal as a crate full of James Brown or Roy Ayers.)

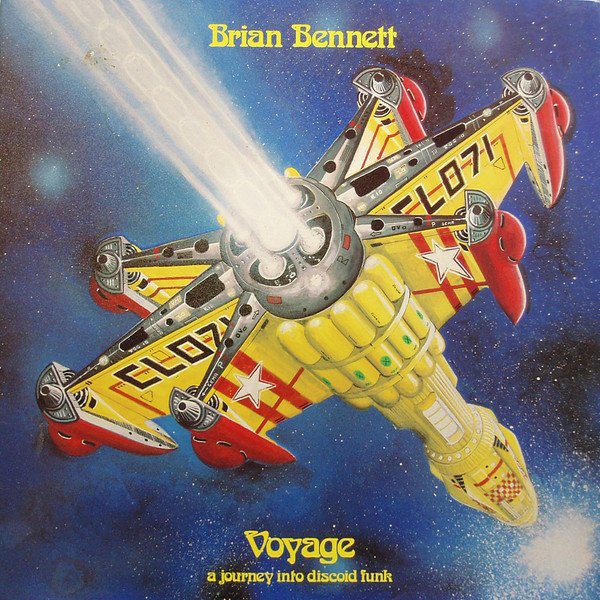

But what does it mean to sit down and listen to this music as… well, as music? Not chopped and flipped, not wafting beneath documentary footage or accompanying a cheap cop show, but as examples of some sort of lost-world corner of soundtracking trends? It can be fascinating to follow some of these pieces as they unfurl in parallel to the more well-known movements in pop, rock, and film scoring — from the swingin’ sixties to early electronic experiments for newfangled color-TV psychedelia, the post-Shaft drive towards heavy funk and smooth jazz, and the synthesized pulse of disco and new wave as the home video age dawned. In isolation, this music ignores any lines between easy-sell commerce and idiosyncratic experimentation, and often creates something so weird that it’s hard to imagine any kind of show or film bizarre enough for that music to score. You’ll find plenty of familiar breaks and samples in these ranks, but odds are you’ll find even more under-explored, self-contained worlds in themselves.