Malcolm Cecil & Robert Margouleff were a pair of producers/engineers/musicians, best known for their synth work, engineering and production on Stevie Wonder’s peerless 1970s run of albums. They also contributed synth programming and performances, composition, production and engineering to a wide range of other musical projects.

Former RAF radar operator and jazz bassist Cecil, who passed away in 2021, met record producer Margouleff in the late sixties. Margouleff had been an early synthesiser adopter, getting his first Moog in 1966 and together the pair set about assembling the largest synth in the world which they christened T.O.N.T.O.: The Original New Timbral Orchestra. T.O.N.T.O was a huge, circular bank of synthesiser modules, based around a Moog modular synth with added modules from other manufacturers including ARP and Oberheim, along with some custom sections created by Cecil. It needed an entire room to house it and both men to operate it.

This was at a time when synthesiser technology was still in its infancy and the pair had to pioneer a number of techniques to realise their musical vision. There was no MIDI standard to easily allow different modules to be synced together and analogue synths often had problems with tuning stability. T.O.N.T.O. was one of the first polyphonic synthesisers (meaning it could play more than one note at a time) and was also one of the very first multitimbral synthesisers, able to produce five different timbres at a time.

In 1971 Cecil and Margouleff released an album using T.O.N.T.O., Zero Time, under the name Tonto’s Expanding Head Band. A few synthesiser albums had already been released in the late 60s, notably Wendy Carlos’ Switched-On Bach and a host of other ‘Switched-On’ albums including Switched-On Bacharach by Christoper Scott and Switched-On Rock by The Moog Machine, but they generally attempted to recreate the sound of traditional instruments using the new Moog and Arp synthesisers. Zero Time was different in that Cecil and Margouleff made little attempt to mimic brass, woodwind or strings but instead created a new sonic vocabulary of synthetic textures. Just listen to the opening track ‘Cybernaut’ and you can hear the fat synth bass tones, smooth pads, synth squelches and clear flute-like timbres that would help to define Stevie Wonder’s seventies output.

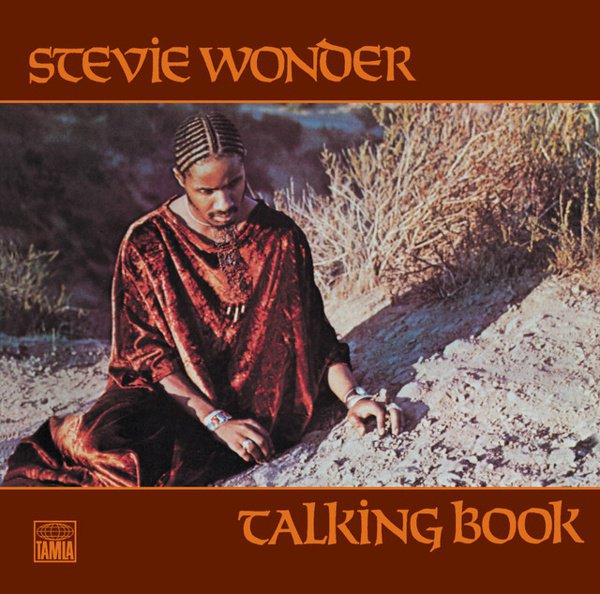

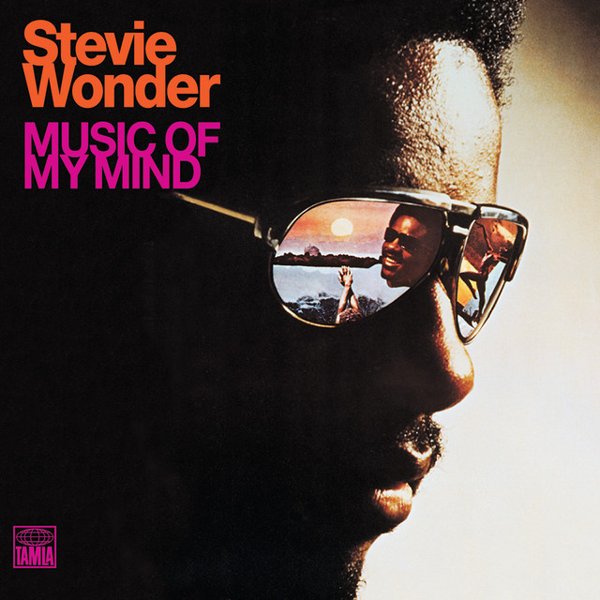

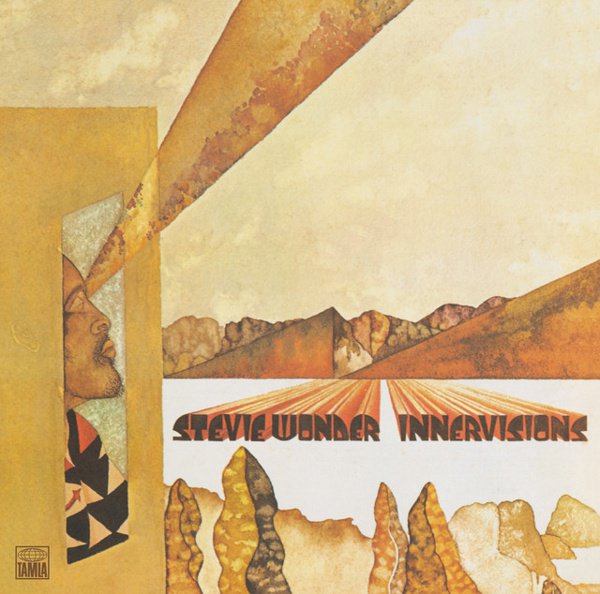

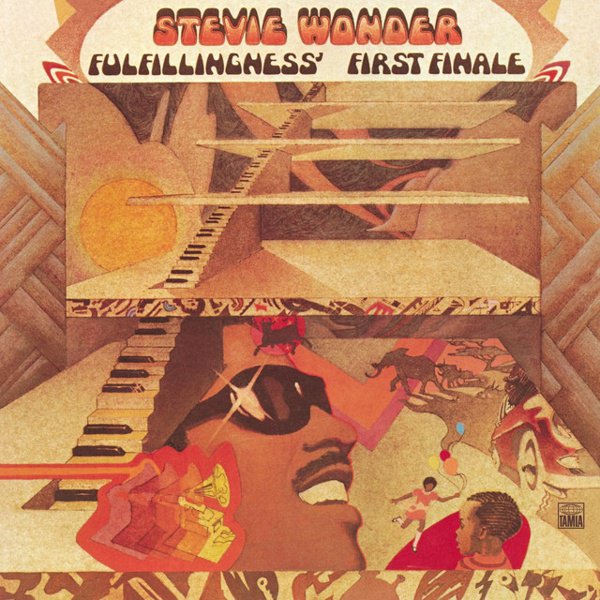

Meanwhile, over at Motown, Stevie Wonder turned 21 in May 1971 and negotiated a new contract that gave him complete creative control over his music as well as more money than any Motown act had ever received before. He was fascinated by the sounds of Zero Time and was introduced to Cecil and Margouleff by singer/songwriter Richie Havens. The three immediately hit it off and Stevie had the entire T.O.N.T.O. setup moved to Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios. There they set to work, beginning a musical relationship that resulted in Stevie’s next four albums: Music of My Mind and Talking Book, both from ’72, Innervisions in 73 and Fullfillingness’ First Finale in ’74, a run of albums that remains unsurpassed in popular music history. Author Craig Werner in his book Higher Ground: Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, Curtis Mayfield, and the Rise and Fall of American Soul said of Stevie’s seventies work that “No musician has ever had a better decade… Wonder offered a sound that rendered the distinction between (soon-to-be “white”) rock and (black) soul meaningless.”

Author Nelson George, in his Motown history Where Did Our Love Go, picks up the tale: “The trio was supposed to work on one album together but, in the words of an ex-Wonder employee, they ‘went nuts. Nuts, nuts, nuts.’ Working evenings, often starting after midnight, working into the daylight and even the next afternoon…in that first year alone they completed thirty-five tracks with Stevie supplying the ideas and Margouleff and Cecil the technology to realise them.” Cecil later estimated that aside from all the material that made it onto Stevie’s albums, they had also recorded around forty other songs and had another 240 that were uncompleted.

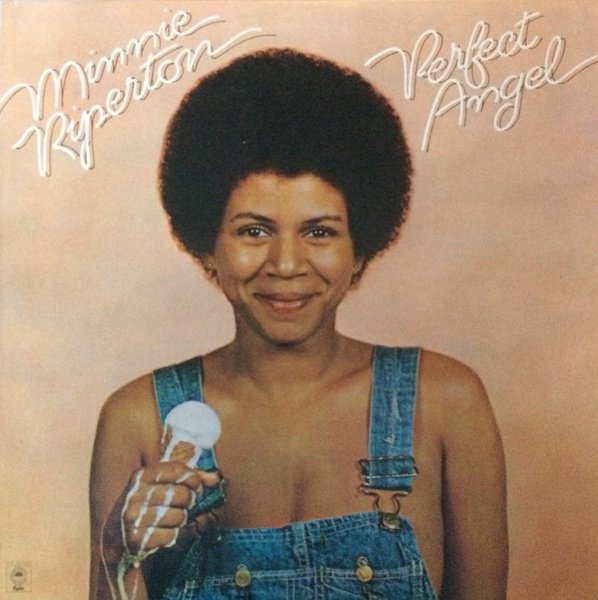

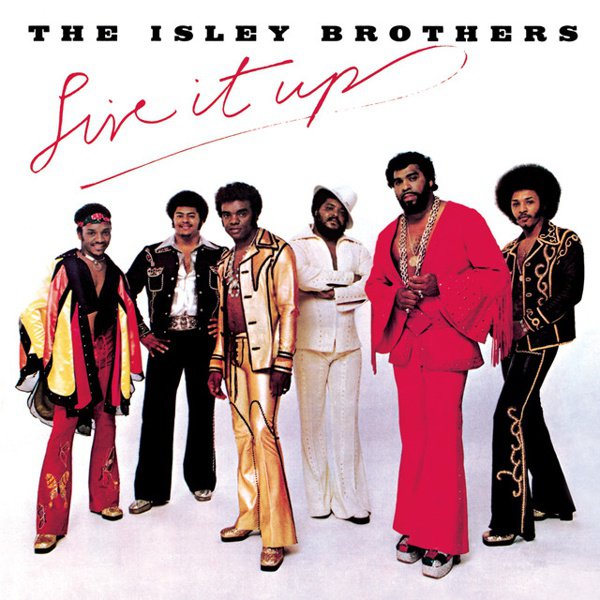

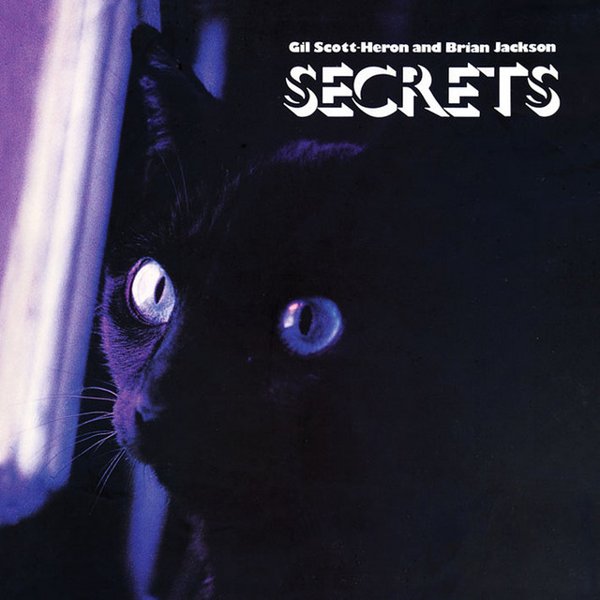

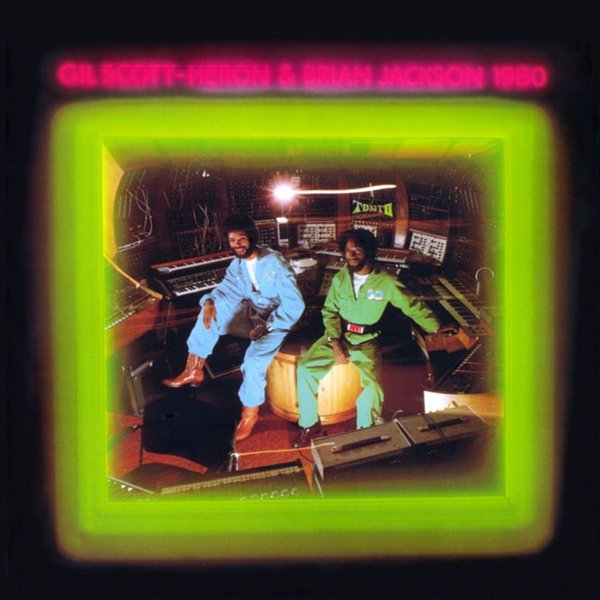

Stevie and Cecil and Margouleff parted company following Fullfillingness’ First Finale due to various disagreements about their working relationship, although plenty of their work with Stevie was included in his Songs In The Key of Life album. Both Cecil and Margouleff were already working with other artists and throughout the seventies provided synth programming and performance, engineering and production for artists including The Isley Brothers, Billy Preston, Mandrill, Minnie Riperton, Gil Scott-Heron, The 5 Stairsteps, Richie Havens, Inner Circle and Quincy Jones.

Together with Stevie Wonder, Cecil and Margouleff completely overhauled the Motown sound and revolutionised the aesthetic of soul music, introducing a new sonic vocabulary of synthesised sound. They pioneered new musical practices that would be embraced by the pop and rock world as the decade progressed and which changed the very sound of popular music - and in the process, they also created a body of vibrant, influential and at times truly wonderful music.