The term “noise rock” is almost deliberately vague; in one sense, it ties rock music all the way back to the beginning of the 20th century, linking it to Luigi Russolo’s 1913 manifesto The Art of Noises. Russolo argues that urban life and machines in particular had effectively retuned the human ear, requiring new approaches to composition and new timbres that would stimulate ears pummeled into submission by factory work, streetcars, etc. On the other hand, anytime we hear a song we don’t like, we say “That’s not music, that’s just noise!” What the pioneering noise-rockers seemed to argue was, What if it’s both? And also, fuck you. Always fuck you.

The crucial factor in noise-rock is the guitar that doesn’t sound like a guitar; instead, it sounds like a sheet of steel being torn apart by robot claws, or an electrical storm, or someone scraping a paper clip across your fillings. So you can trace the roots back to the second Velvet Underground album, 1968’s White Light/White Heat, and follow a line of jagged tin-snips riffage that includes King Crimson circa Larks’ Tongues in Aspic and Starless and Bible Black, Gang of Four’s Entertainment!, Public Image Ltd.’s Metal Box, and Siouxsie and the Banshees’ The Scream. (Of course, one could also argue that John Lee Hooker pioneered noise-rock guitar on the 1963 album Don’t Turn Me From Your Door — the disjointed, almost detuned instrumental “I Ain’t Got Nobody” is stunning.)

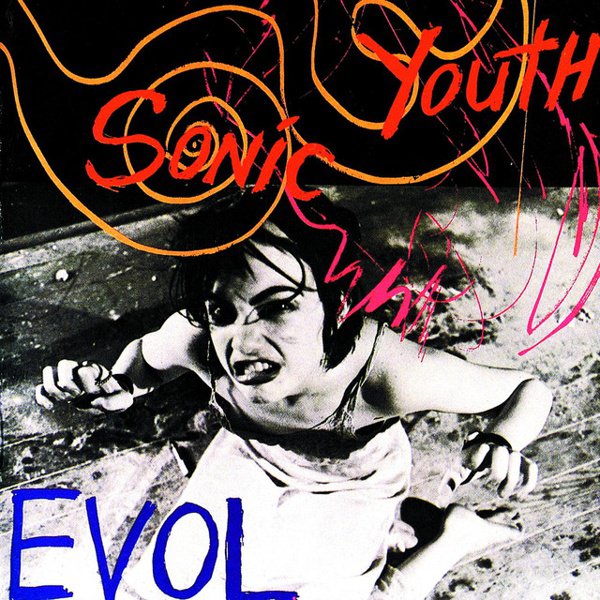

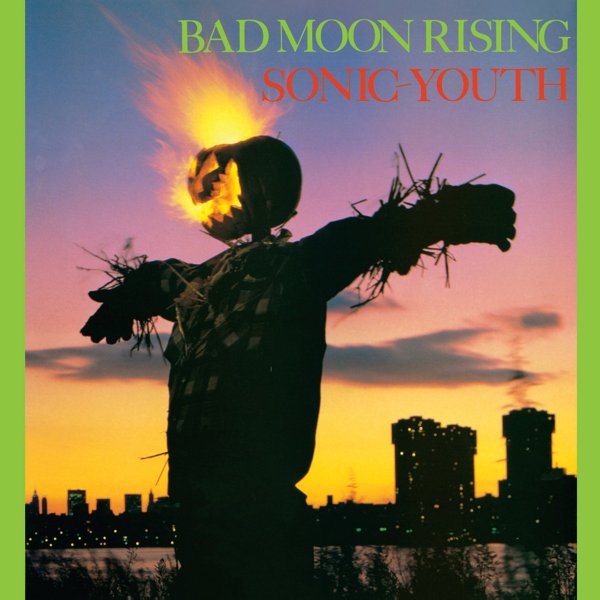

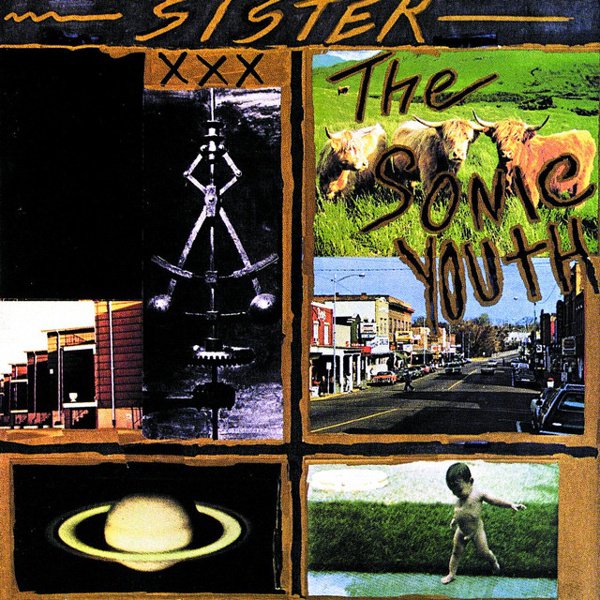

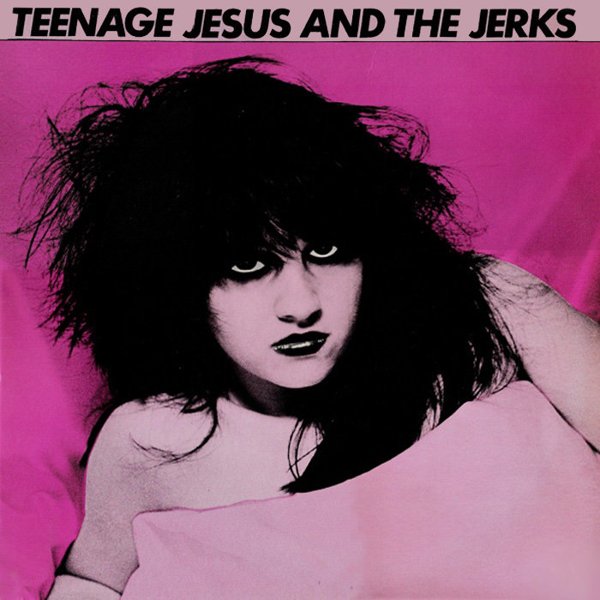

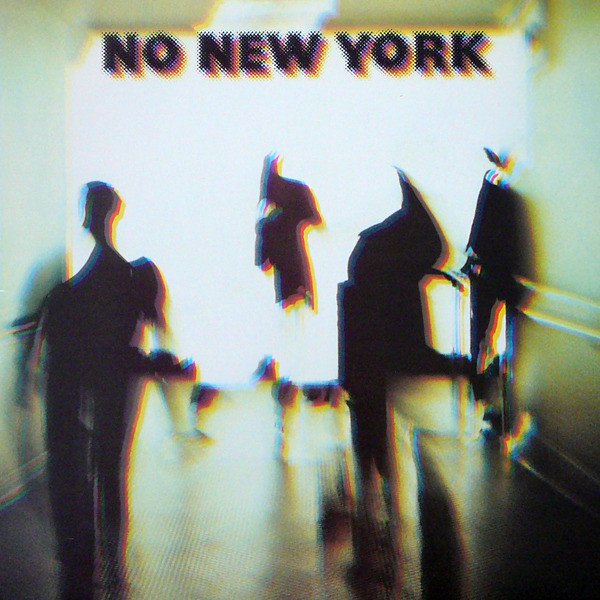

Another crucial jumping-off point was the 1978 compilation No New York, which featured four Downtown groups — Teenage Jesus & the Jerks, the Contortions, Mars, and DNA — whose music was like having one’s face scraped along the sidewalk. Late ’70s/early ’80s New York was a natural incubator for noisy music. Groups like Swans and Sonic Youth were reflections of their environment — their music clanged and rattled and throbbed like subways and garbage trucks and sirens, like your neighbor ranting and raving from down the hall, and it had a kind of innate psychic pressure that matched the stress of living a financially precarious life in a broken-down, dangerous city. Thurston Moore, Kim Gordon and Lee Ranaldo trafficked in a kind of near-hallucinatory alienation, as though trying to dream themselves out of their surroundings, while Michael Gira chose to wallow (the first Swans album was called Filth) and deliver anguished slogans about fear, power, and subjugation.

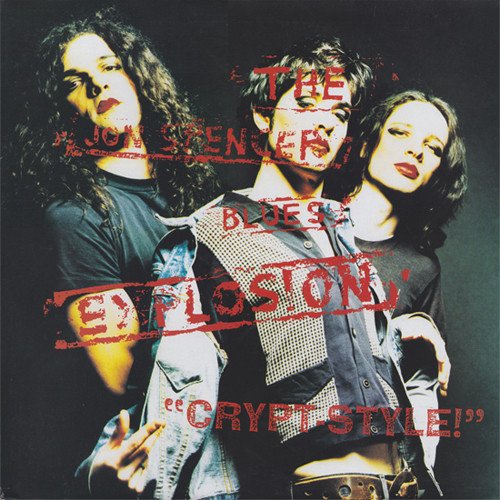

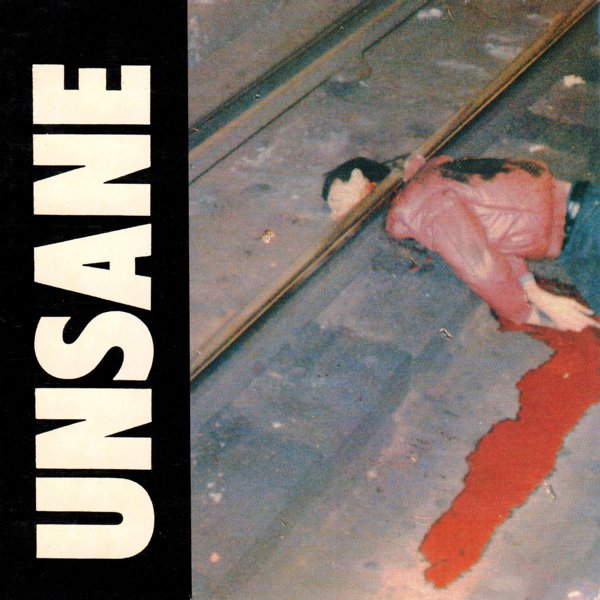

A few years later, a second generation of noise-rock bands began to emerge from New York’s Lower East Side. Among the most prominent were Pussy Galore, fronted by Jon Spencer and propelled by Bob Bert’s junkyard percussion (instead of a snare drum, he struck a car’s gas tank), and White Zombie, led by Rob Zombie. These bands and their peers (Rat At Rat R, Live Skull, the Reverb Motherfuckers and more) were the audio equivalent of a dirt-encrusted porn magazine found in the woods, embracing a clanging, head-bashing rock ’n’ roll primitivism and filling their lyrics with references to trash culture, while giving off a hostile vibe that was much more nihilistic and socially disengaged than the hardcore punk bands they shared performance spaces with. Still, Spencer and Zombie had star quality. Unsane frontman Chris Spencer, meanwhile, was more of a working-class blues shouter, armed with a Fender Telecaster that could slice your face open.

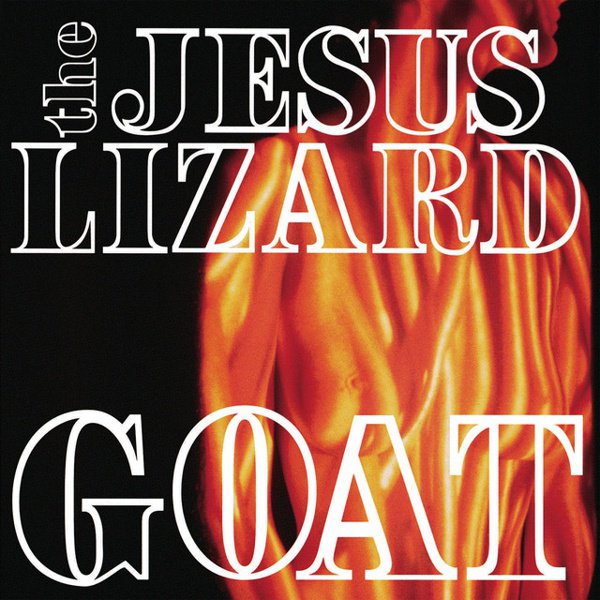

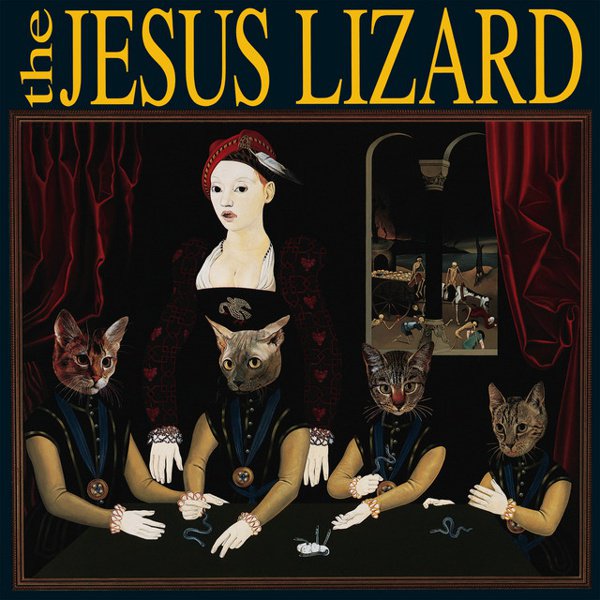

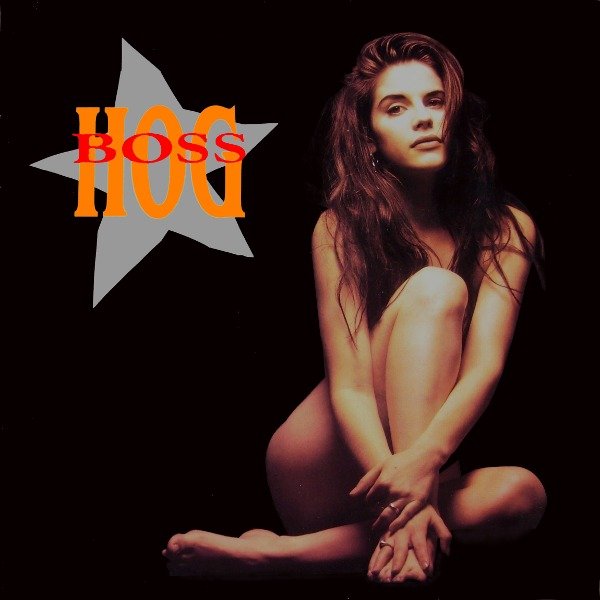

The blues was a surprisingly strong element of second-generation noise-rock; bands like the Chrome Cranks, the Honeymoon Killers, and others seemed as descended from the early Rolling Stones, the Pretty Things, and even the Cramps as Swans or Sonic Youth. And when Midwestern acts like Killdozer, Cows, and the Jesus Lizard joined the party via Chicago and Minneapolis, not to mention Texas’s Butthole Surfers, things got even more macho and swaggering, as they yowled and roared surreal portraits of rural and white-trash life atop thudding drums and bone-scraping guitars. That’s not to suggest that noise-rock was a boys’ club, though, as Lydia Lunch, Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, White Zombie’s Sean Yseult, Pussy Galore’s Julie Cafritz (and Cristina Martinez, who’d form Boss Hog with her husband, Jon Spencer) were just a few of the female voices who helped define the genre.

If the twenty recommendations below aren’t quite enough, check out Phil’s expanded list here.