Every major American city has a moment or two where it gets to lay claim on American popular culture when New York and Los Angeles are caught unawares. Detroit and Memphis in the ’60s, Minneapolis and Miami in the ’80s, Seattle in the early ’90s, Atlanta for the past couple decades — all of them have contributed the sorts of ideas, cultures, and settings that you can’t get from the two big coastal centers. And few metropolitan cultural centers echoed across a decade like Philadelphia did during the long Seventies. This was the stomping grounds of Mike Schmidt and Dr. J and Smokin’ Joe Frazier and the Broad Street Bullies edition of the Flyers, the Bicentennial city that birthed the era’s ultimate feel-good sports hero in Rocky Balboa — and, most enduringly, the sound of Philadelphia soul, a phenomenon that would permanently define an era and a style even more than it defined its origin city.

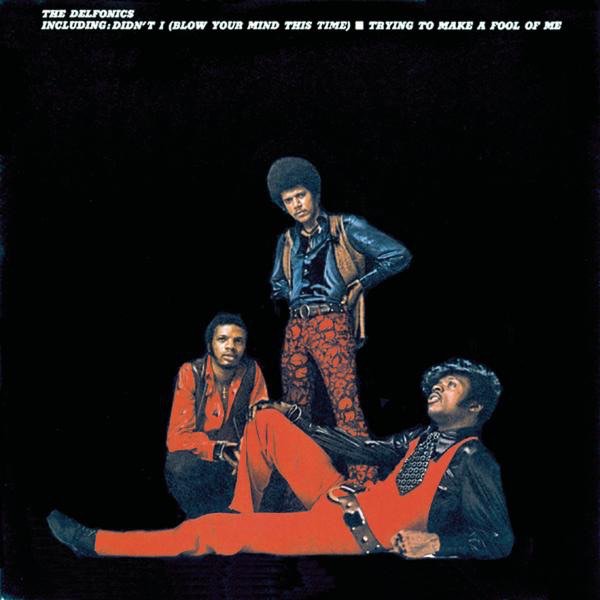

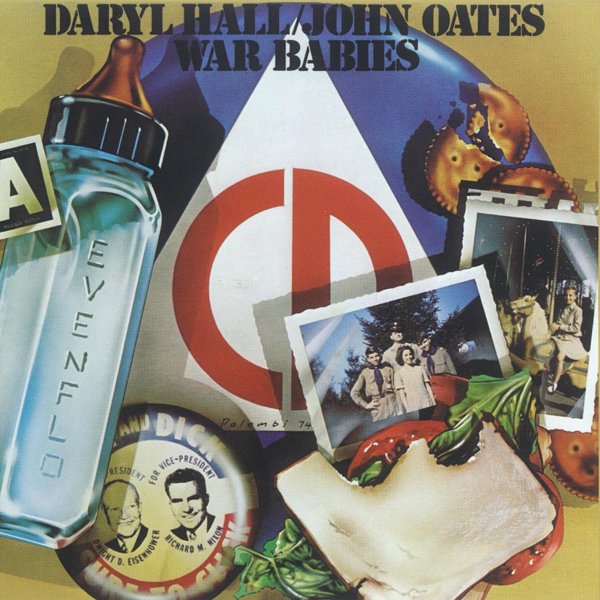

The roots of Philly soul run deep, but 1968 is a good place to pinpoint the hey maybe we’ve got something here moment. That was the year Joseph Tarsia opened the doors of Sigma Sound Studios, the state-of-the-art facility that boasted one of the earliest 24-track recorders in the country, and ushered in the possibility for the regional soul scene to become the epicenter of a newly upscale, hi-fidelity take on R&B. That was also the year Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff, already crossover hitmakers with the Soul Survivors’ 1967 surprise smash “Expressway to Your Heart,” notched their first R&B #1 as both songwriters and producers with the Intruders’ “Cowboys to Girls.” With the September ’67 shutdown of legendary regional label Cameo-Parkway, other songwriter/producers who’d made their first strides there would find bigger things sooner or later — the former in the case of Thom Bell, who helped mastermind the ’68 Delfonics hit “La-La (Means I Love You)”; the latter in Bunny Sigler, a do-it-all singer/songwriter/producer/arranger who Gamble and Huff would add to their growing ranks by the turn of the ’70s.

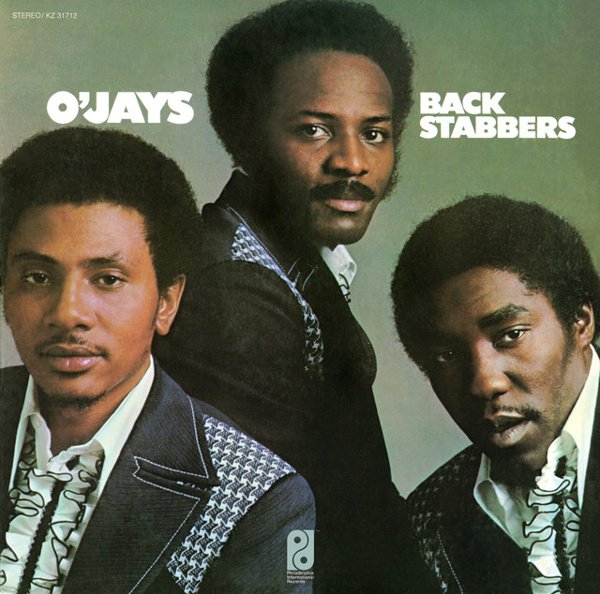

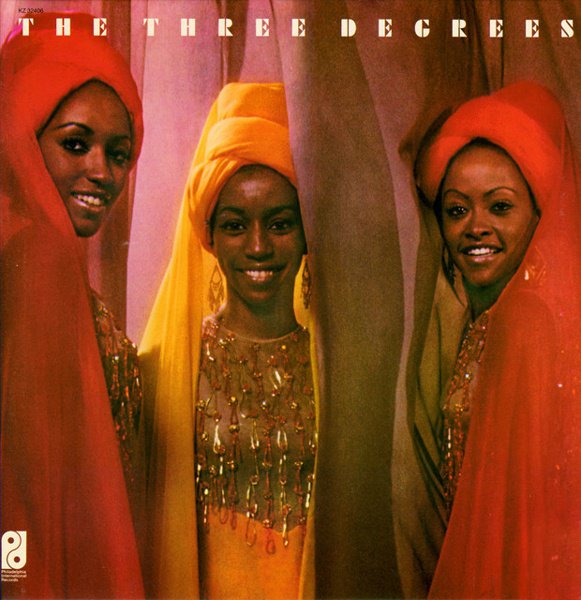

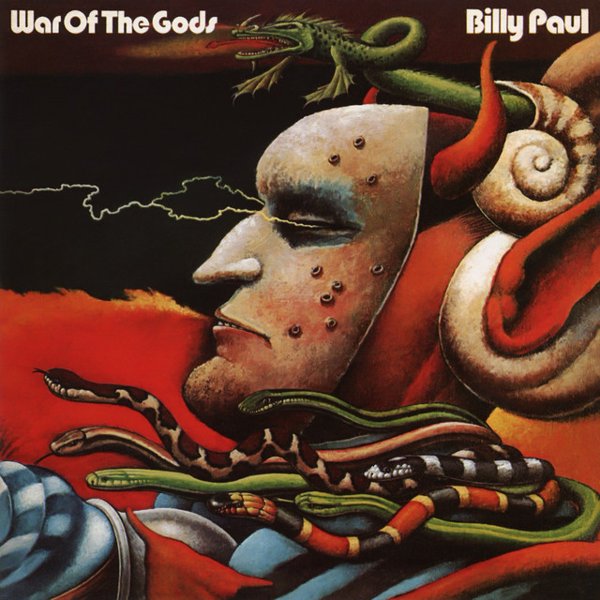

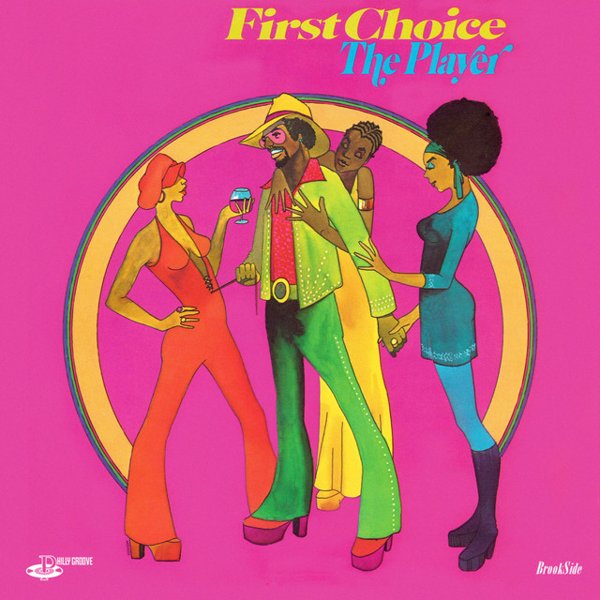

It’s that turn of the ’70s, in fact, that Philly soul started to hit its stride — a long, continent-spanning stride that would put its own trademark on the charts, the dancefloor, then the globe. (After all, the early signature tune of MFSB — the tirelessly omnipresent session band of the scene — was titled “The Sound of Philadelphia,” but its hook called out to “people all over the world,” a reiteration of the O’Jays’ smash-hit chorus to “Love Train”.) To hear the sound of Philadelphia in 1970 is to hear a strange new notion of sweet-stringed R&B mutate easy listening into intimate listening. And then, to hear it in 1973 — as a colossal edifice of symphonic sweep, fused to a better-than-metronomic, subwoofer-caressing sense of rhythm and groove, and best paired with singers who held absolutely nothing back — was to hear the sound of so much more that followed, perfecting the possibilities of disco so thoroughly that Giorgio Moroder had to practically invent synthpop just to transcend it. This music was often derided at the time as overly slick or even bourgie, but it also feels like the last great movement of purely analog R&B — macroscopic as it was — before the advent of synths and sequencers opened another door to a far different world.