It’s 1985 and Ryuichi Sakamoto sits before the camera of French filmmaker Elizabeth Lennard. She’s capturing the Japanese superstar for a documentary film, Tokyo Melody, which is tangentially a music documentary. But with its non-linear structure, bursts of technological color, and the philosophical musings of its subject, it reveals the long shadow cast by another French film, Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil, released just two years prior. It also echoes Sakamoto’s own musings on time.

“People compose their music from the first till the last note following a chronological order,” Sakamoto says. “But now, we can, for instance, start at the middle, memorize it, continue another part and memorize that. The notion of a piece of music is we can put each memorized part anywhere, so time is no longer linear. Time does not develop in one way. We have a block of divided times. We can compose music and put it in any order we like.”

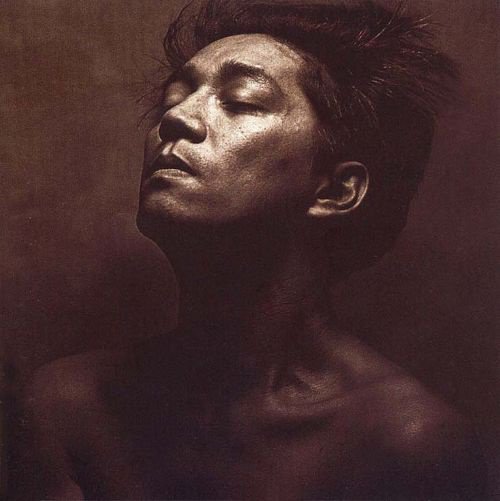

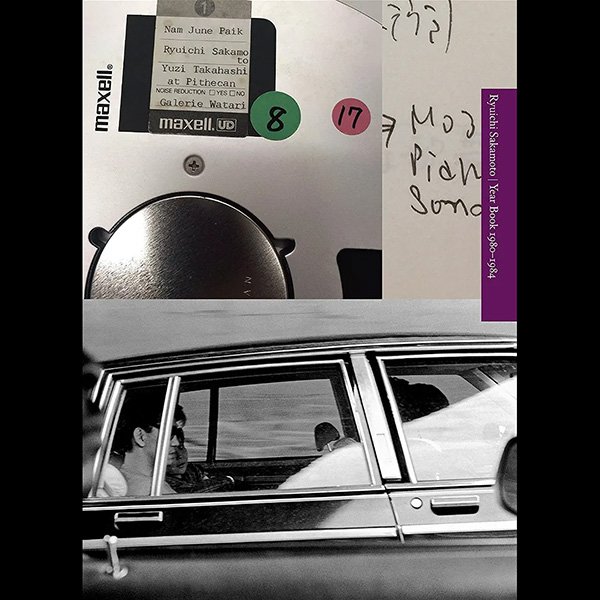

The film captures Sakamoto in a curious period of his life, just after his successful group Yellow Magic Orchestra disbanded and after he’d crossed over to the silver screen with his role opposite David Bowie in director Nagisa Ōshima’s film Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. He’s working on Ongaku Zukan, an album which will take nearly two years to finalize, while also putting in long hours composing music for commercials. As both that album and the film make clear, he’s enamored with the infinite possibilities of the new technology, loading giant eight inch floppy disks into a Fairlight C.M.I. and stating that “any kind of sound will be OK.”

That cast-off line became a mantra of sorts. Sakamoto was economical, and could find something that resonated in almost any noise, melody, or new-fangled gear. Throughout his career Ryuichi Sakamoto struck a balance between West and East, between the European classical canon (which he absorbed while earning his master’s in music composition at Tokyo University) and the cutting edge technology emerging from modern Japan. Barely out of college, he was in-demand as a session player in Tokyo.

And when Haruomi Hosono conceived of a band that would “arrange Martin Denny’s ‘Firecracker’ as an electric chunky disco using synthesizers and sell four million copies of the single worldwide,” Sakamoto went along with it, soon finding himself caught up in the tsunami of pop stardom as a member of Yellow Magic Orchestra and firmly entangled within the wires of ascendant synthesizer technology. The group’s bond always seemed unstable, their personalities not aligned, the group disbanding at their peak in 1983, reforming in the ‘90s, then begrudgingly cashing in on live tours over the years. (In 2018, Hosono played his first ever live shows outside of his native Japan, including a date at London’s Barbican Centre. Not even three miles to the north, Sakamoto was part of a residency at Café Oto. At the last minute, he was convinced to take the stage with his old bandmates, the last time all three members of Yellow Magic Orchestra would play live. As the final notes of “Absolute Ego Dance” faded out, Sakamoto dashed back out the door.)

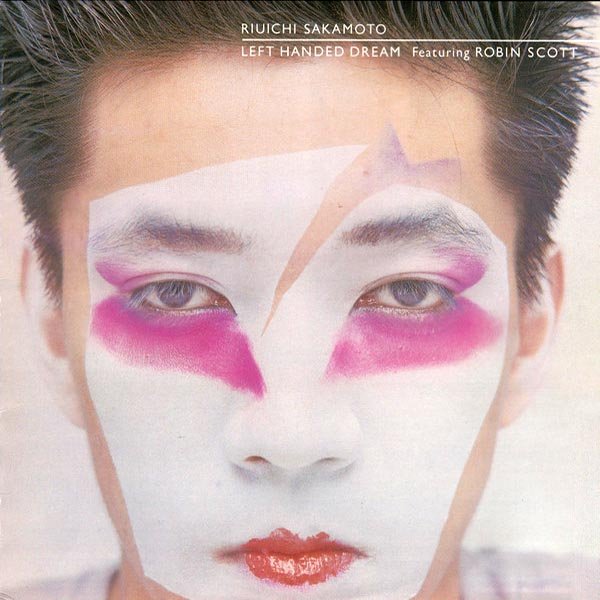

Sakamoto had a more uneasy relationship with fame and celebrity than Hosono did. He sought out the largest possible platforms in order to disseminate his music as widely as he could. He worked often with the biggest pop stars emerging from the UK, including David Sylvian, Thomas Dolby, Robin Scott, Andy Partridge, and more. TV and film scores were often his priority and he garnered Grammys and Oscars along the way. In the 1990s, his zealotry to be everything to everyone became acute, his major label albums teeming with guests and slick new sounds. As one album title Esperanto suggested, it could seem like Sakamoto was in search of a universal musical language.

At the turn of the century, Sakamoto pivoted back to his avant-garde roots, collaborating with new players who also wedded melodicism and electronics to abstract and visceral ends. And rather than being the solo star and primary focus, he reveled in collaboration and equal dialogue. Such conversations became his primary focus over the last two decades of his life.

Sakamoto was always open to utilizing technology to further his true mission in music, which writer Sasha Frere-Jones described as an exploration of his very humanity amid the machines, “the vulnerable nature of his search…the questions that every artist confronts: What does consciousness feel like? Why is experience so dry and mute, and then, on other days, so completely overwhelming?” Whether constructing bittersweet movie themes or finding music within the austere crackle of circuitry, Sakamoto mastered both approaches.

![The Revenant [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/6025067512201216_600.jpg)

![音楽図鑑 [Ongaku Zukan] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/6295948069437440_600.jpg)

![Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5116979142197248_600.jpg)

![The Last Emperor [Original Soundtrack] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5663302037536768_v1_600.jpg)

![子猫物語 [The Adventures of Chatran] cover](https://images.theshfl.com/5663975575650304_v1_600.jpg)