At first glance, the Salsoul label — established in 1974 and decommissioned roughly ten years later — seems like a simple-enough chapter in the story of disco’s momentous rise and fall. They struck while the iron was hot, notched a lot of clubland classics and a handful of minor pop-crossover successes, earned a loyal following among the disco cognoscenti beneath the radar of a largely skeptical rockist music press, and then receded from the spotlight when the disco market hit its early ’80s downturn. But in another, more tangled sense, Salsoul’s story hinges on both incredibly fortuitous luck and inexplicable star-crossed tumult — the kind of thing that only really happens when a ruthless business sense grapples with artistic demands and winds up staggering into a brief but rare win-win.

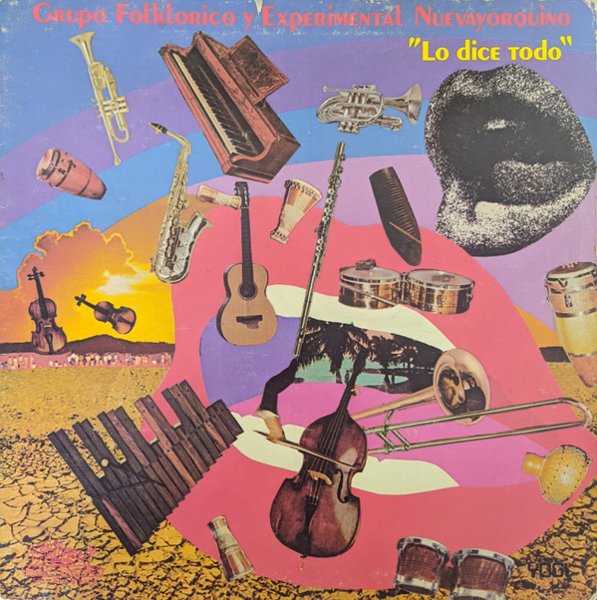

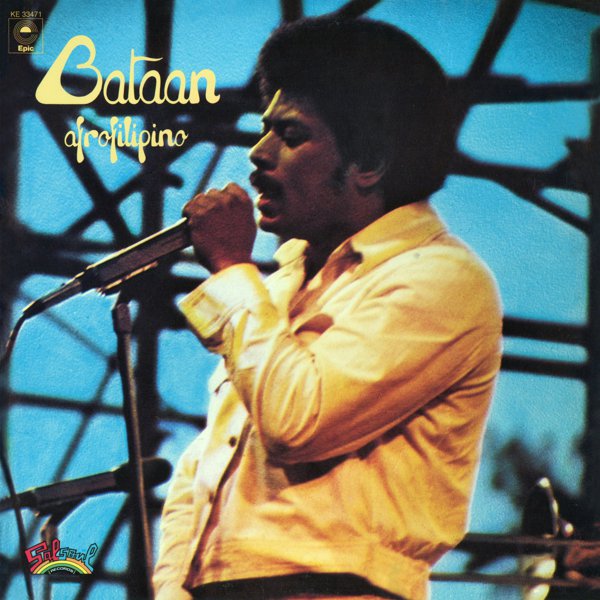

The Cayre Brothers, Joe, Ken, and Stanley, were a nomadic sibling trio with a history of getting into every kind of business from duty free retail to nylon hose to plastic injection molding. Eventually they found their way into the music biz, and after some awkward misunderstandings and false starts — including a copyright-flouting enterprise selling 8-tracks of CBS and RCA’s Mexican-market recordings in the U.S. Southwest without actually securing the American rights — they found a promising niche in the New York Latin music scene. After the brothers transitioned from distribution to helming an actual label, Mericana Records, Joe Cayre pulled the surprise coup of signing Latin-music star Joe Bataan after the popular singer grew disillusioned with Fania Records’ stingy payouts. Bataan gave his first (and only) album on Mericana the title Salsoul, a fittingly characteristic portmanteau of “salsa” and “soul,” and while it didn’t move units, it did get the most crucial co-sign any New York soulster would ever want when tastemaking WBLS DJ Frankie Crocker put Bataan’s instrumental Deodato cover “Latin Strut” in heavy rotation.

After selling CBS the short-term rights to the record for $100,000, the Cayres figured that more music like “Latin Strut” — danceable, uptempo, funky and soulful Latin-inflected instrumentals — might make a few bucks off the growing New York trend of DJ-driven dance clubs. Bataan agreed, and had designs on starting a label — something the Cayres were more than happy to support. Goodbye Mericana, hello Salsoul. Bataan’s efforts were just the first part — though it would soon become apparent that an A&R role and 25% partnership in the new label with the Cayres would be the best offer he could get. (He’d eventually lose his share in the business, but not before he released a pioneering early rap single, “Rap-O Clap-O,” on the label in 1979.) And while their efforts to cultivate a roster of Latin music stars outside the increasingly constricting aegis of Fania gave them a foothold in the New York music world, it was the Cayres’ opportunity to take advantage of another city’s foundational scene that put Salsoul over the top. Many of the musicians who’d written and played on all those big Philly soul hits for Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff’s Philadelphia International Records had, like Bataan, started to resent how light their pockets were feeling despite their integral role in a massive corpus of R&B hits. Ken Cayre, already being enamored with the Philly sound, had made the decision to start assembling a studio group that would emulate its symphonic-yet-danceable power — and instead of looking for ringers, he wound up discovering that the working musicians and arrangers of PIR were more than willing to jump ship themselves. In signing arranger/vibraphonist Vincent Montana Jr., singer/songwriter Bunny Sigler, and the production/writing/musician unit of Norman Harris, Ronnie Baker, and Earl Young, Salsoul essentially siphoned the Philadelphia Sound into their own vision at just the right moment for that sound to become even more lucrative than it was in the early ’70s.

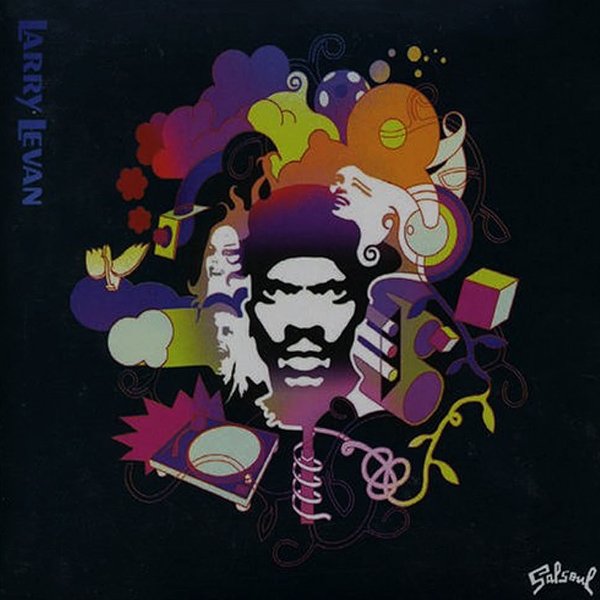

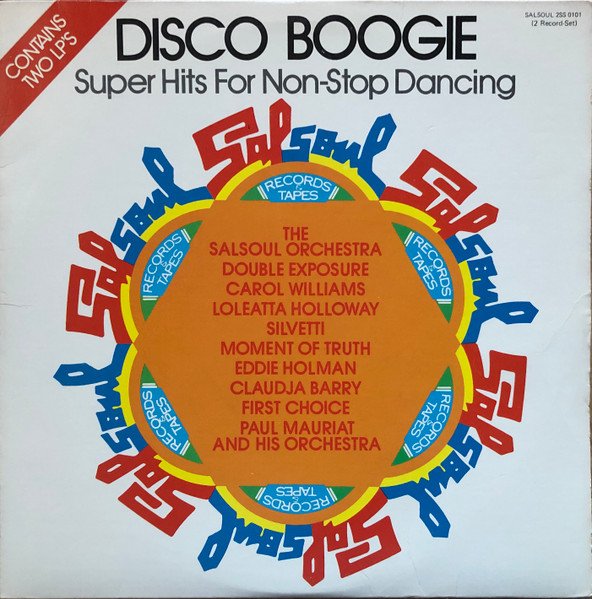

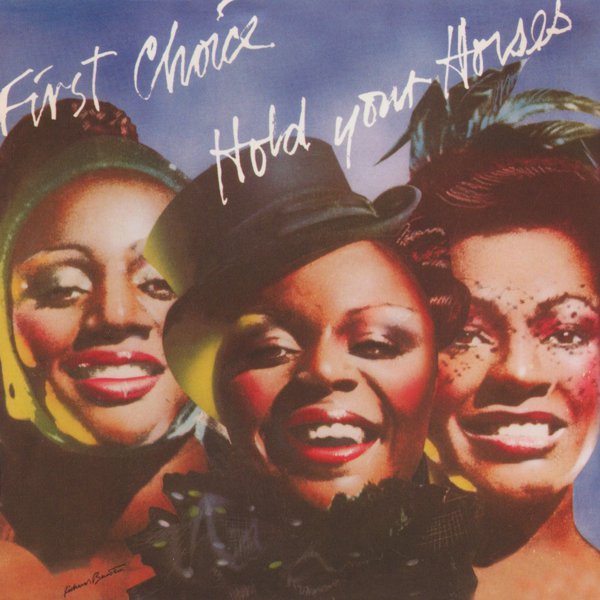

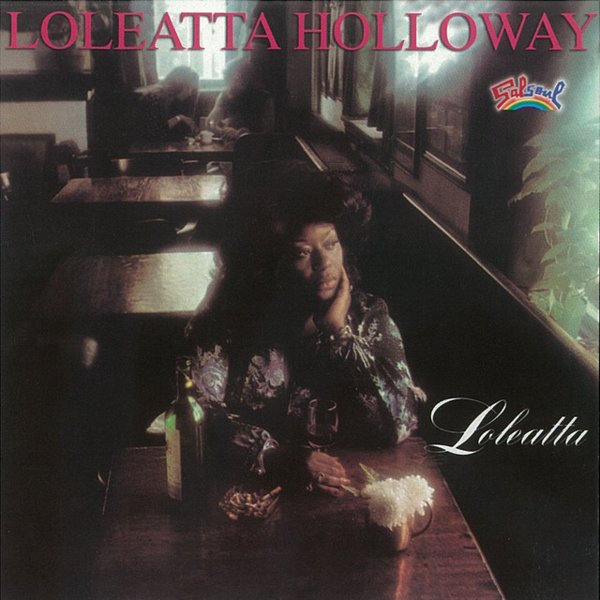

While the sales-driven and airplay-focused mainstream charts rarely took notice, Salsoul would thrive for years just off the strength of how well their records did in clubs. While their soul offerings were strong — both on Salsoul proper and its Norman Harris-helmed subsidiary Gold Mind — Salsoul soon became synonymous with disco, for better and for worse. The “worse” is subjective anyways — there have been far more grievous sins committed on the genre’s behalf than kitschy Christmas albums and Charo records — and the “better” in this case is just about the best American disco ever got. And above all else, Salsoul’s role in DJ culture was pivotal to the point where it’s hard to imagine how things would’ve panned out without them. Their hold on the disco world was driven by prescient innovation that was borne out of necessity: taking the then-unusual risk of pressing singles on 12” records, putting out a 1977 double LP (Disco Boogie) that served as one of the earliest and best commercially released dance mixes, and giving shine to a new movement of DJs who refused to settle for merely playing records when they could transform them. Walter Gibbons, Tom Moulton, and (especially) Larry Levan built up the Salsoul pantheon one remix at a time, and while the best collections of these mixes — particularly the early ’90s Classic Salsoul Mastercuts entries and the stunning two-CD 2004 compilation Larry Levan: The Definitive Salsoul Mixes ’78-’83 — are woefully absent from streaming platforms, they’re worth seeking out by any means available as the next step after immersing yourself in this wide cross-section of what albums Salsoul had to offer in their heyday.