Since its emergence in the late ’80s, first as a more primitivist, aggressive outgrowth of thrash and then as its own thing once certain stylistic trademarks like the blast beat and guttural “Cookie Monster” vocals became established, death metal has been a playground for musicians interested in all types of extremity. Drummers who want to play faster than anyone before them; guitarists who want to yoke harmonic complexity and even atonality to headbanging fury; producers who want to explore nearly subsonic levels of bass: all find a home in death metal’s musical sub-basements.

Throughout the genre’s early history, regional scenes sprang up, and small groups of like-minded bands focused on narrow micro-styles. The most obvious of these was in Sweden, where post-Motörhead rock ’n’ roll riffing was fused to D-beat rhythmic pummel, but in Florida, a school came together to push the music toward increasing compositional intricacy. Guitarist Trey Azagthoth’s Morbid Angel abandoned traditional scales as they flew off into mind-blasting psychedelic explosions; Cannibal Corpse may have seemed like straightforward bashers, but bassist Alex Webster was a stealth virtuoso and the band’s guitarists frequently threw in more flourishes than were strictly necessary; while Atheist and Death (and later Cynic) infused their music with elements of jazz and progressive rock.

In the mid to late 1990s, a few acts began to refine the Floridian language, focusing on extreme precision and ultra-clean production. Death metal’s key features — downtuned guitars; machine-gun drumming; guttural vocals — are mostly concentrated in the lower frequencies, which makes it a challenge to mix the music without turning the whole thing into a muddy mess. But technical death metal (“tech-death” for short) set out to solve that problem via sampled drum triggers, guitars fed straight into the mixing board, and other state-of-the-art engineering achievements. At the same time, their songs shrugged off traditional verse-chorus structure in favor of dense collages of riff upon riff, and ear-piercing solos laid atop blindingly fast, hit-everything-twice drumming.

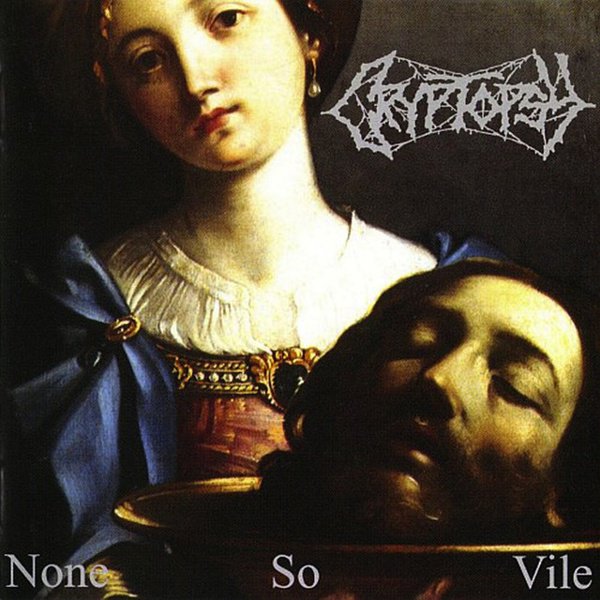

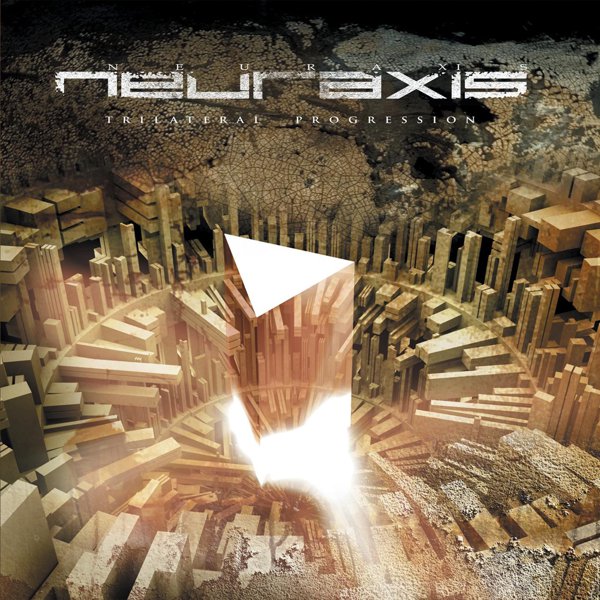

In the early 2000s, tech-death really hit its stride, with bands from all over the world competing in a kind of musical arms race that made the art-metal high-water marks of previous decades, like Metallica’s …And Justice for All and Megadeth’s Rust in Peace, sound like Ramones demos. For whatever reason, French-Canadian bands (Gorguts, Cryptopsy, Neuraxis, Martyr, and more) really took to tech-death, but groups from Germany (Necrophagist, Obscura) and various US states (California’s Decrepit Birth, New York’s Suffocation, Kansas’s Origin) released landmark albums as well. And then there was Sweden’s Meshuggah, whose music layered seemingly conflicting rhythms and time signatures over each other until you couldn’t even headbang to it without a calculator. These days, technical death metal has achieved a kind of airless, gleaming sterility, like a highly polished spaceship, but the guttural, nearly pre-linguistic vocals make certain that the human element never disappears completely.