Country music has always been a battleground between the traditional and the modern. Its songs are an attempt to fuse the values of past generations, including the acoustic instruments played by rural people for hundreds of years, with life in 20th and now 21st century America. That tension is what gives the best country its vitality and joy. And the “Bakersfield sound” might exemplify that tension better than any other style of country.

The Bakersfield sound, as its name suggests, developed in California. The performers who brought it to national attention, like Buck Owens and Merle Haggard, came up in the 1950s and early 1960s, but its roots go back to the 1930s and 1940s, when economic migrants from Oklahoma, Texas and the “dust bowl” came to California seeking farm work or jobs in the oil fields. Legendary “western swing” bandleader Bob Wills, whose Texas Playboys combined country songwriting and hillbilly fiddling with a jazz rhythm indebted to Count Basie, was in fact based in California after World War II. Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry didn’t allow performers to use drums onstage, but out in Bakersfield, the hard-drinking farmhands and oil patch workers wanted to hear a backbeat.

In the Forties and early Fifties, acts like Lefty Frizzell and the Maddox Brothers and Rose were making music with an intense, wired-up energy (the Maddox Brothers and Rose’s instrumental “Water Baby Blues” is a hillbilly rave-up with stinging electric guitar played at bebop speed) and a lyrical worldview that reflected their circumstances. Frizzell was a songwriter the equal of Hank Williams, but more romantic and less doom-haunted, focusing on songs of heartbreak, and his guitar-centric arrangements leaped out of radio speakers. Other key early figures included Tommy Collins, Billy Mize, Wynn Stewart, and Jean Shepard.

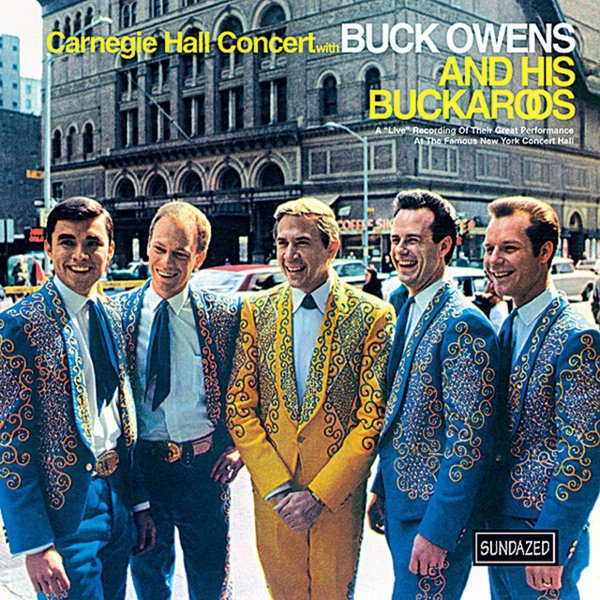

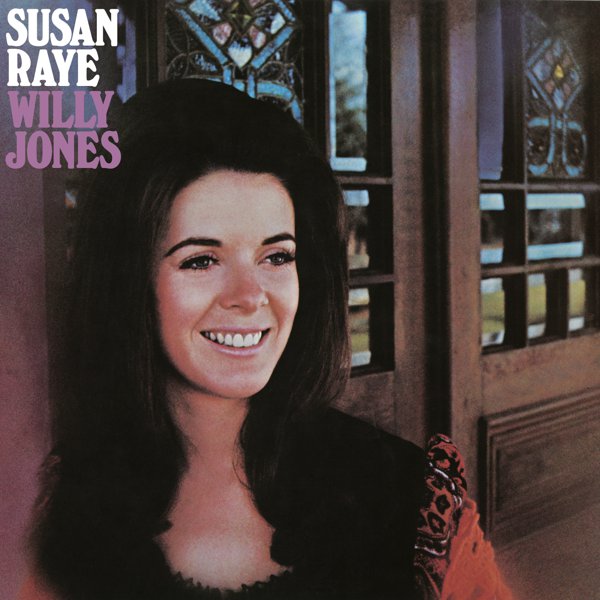

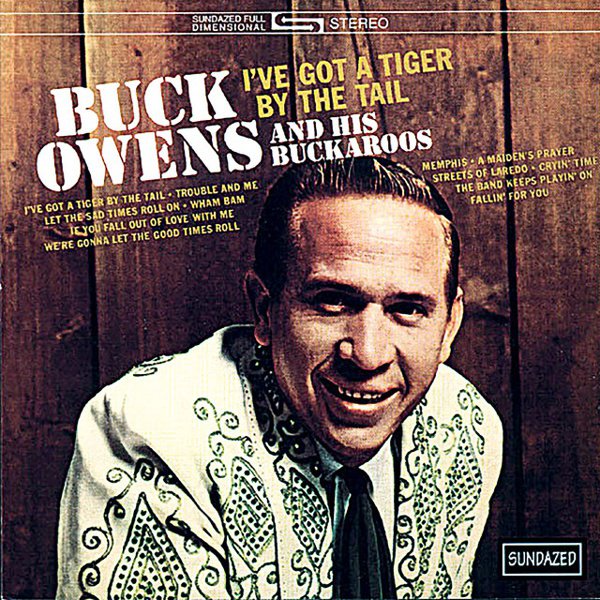

The song credited with creating the classic “Bakersfield sound” is Bud Hobbs’ “Louisiana Swing,” from 1954. Hobbs shouts out the pianist, “Billy Woods from Bakersfield,” before his solo, and then names the guitarist — Buck Owens. Beginning in the early Fifties, Owens was a session musician for Capitol Records, recording with Tennessee Ernie Ford, Wanda Jackson, Tommy Collins, and others. Eventually, he began recording as a leader, forming the Buckaroos; their song “Under Your Spell Again” was a #4 hit in 1959. Throughout the Sixties and into the early Seventies, Owens was a major hitmaker; songs like “Act Naturally” had the lyrical wit of the best country but set it to a rock ’n’ roll beat that allowed the Beatles to cover it without sounding like they were doing hillbilly kitsch. (Owens, in turn, played a Beatles-style version of the Isley Brothers’ “Twist and Shout” when he and the Buckaroos appeared at New York’s Carnegie Hall.) Eventually, Owens was enough of a commercial powerhouse that he was able to produce hits for others, including Susan Raye, his ex-wife Bonnie Owens, Buckaroos guitarist Don Rich, and more.

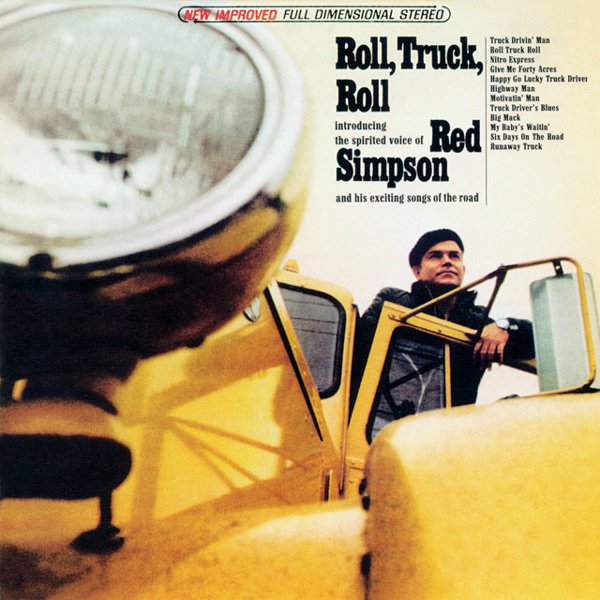

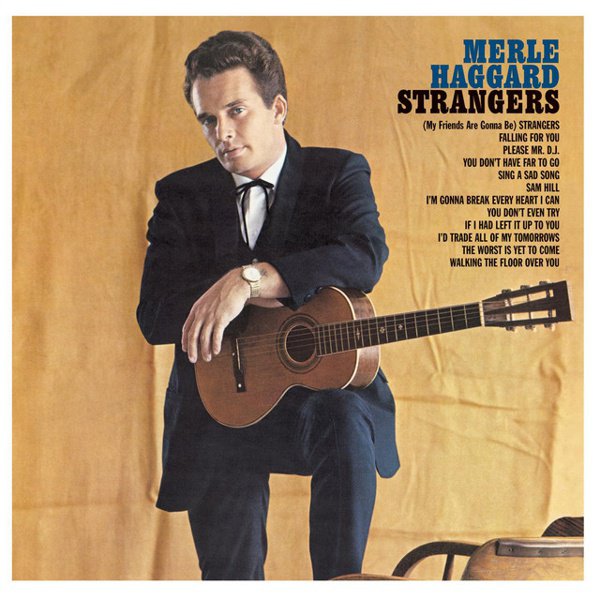

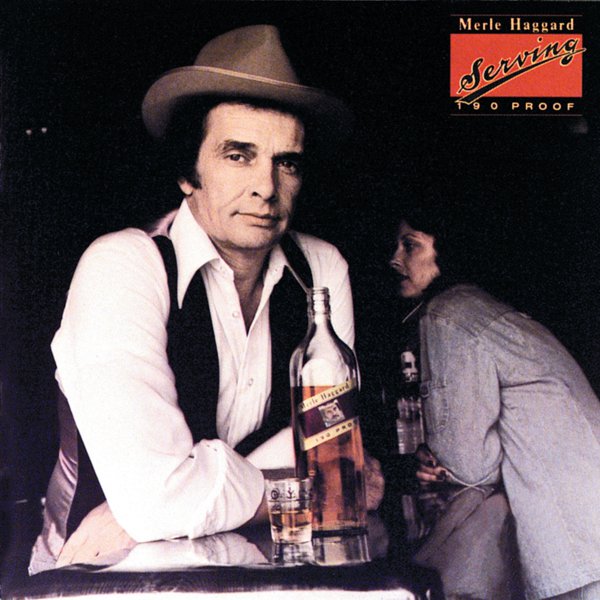

Merle Haggard and his band the Strangers followed Owens up the charts, his hard-bitten songs inhabiting the perspective of the working class descendants of the Okies. Haggard’s people were people for whom the Great Depression was more than just a memory — the specter of poverty hung just over their shoulders every day, so if they turned to crime, it was sad but understandable. Another act with a similarly working-class perspective, albeit a uniquely focused one, was Red Simpson, almost all of whose songs were about long-haul truckers.

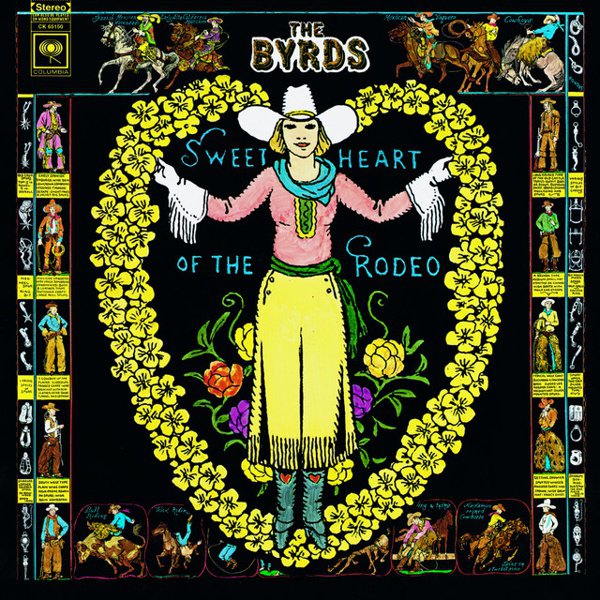

In the late Sixties and early Seventies, the Bakersfield sound, which had taken influence from early rock ’n’ roll, began in turn to influence newer rock acts. The Byrds made Sweetheart Of The Rodeo, an overtly country-fied album, and even the Grateful Dead (who covered Haggard’s “Mama Tried”) slid from amorphous psychedelic soundscapes into concise, twangy songs. And then in the Eighties, a new face emerged to bring the Bakersfield sound into the modern era.

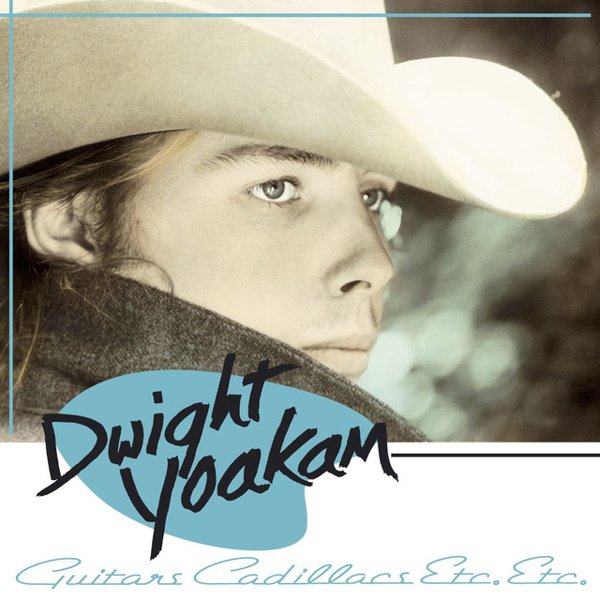

Dwight Yoakam moved to California from Ohio, and like the migrants of fifty years earlier, found himself struggling to break through. But once he started playing Bakersfield-style country in punk-rock bars, on bills with acts like Los Lobos, X and the Blasters, his nasal twang and barbed-wire guitar — and his sharp, creative songwriting — rapidly earned him a sizable fan base. On his third album, 1987’s Buenas Noches From a Lonely Room, he collaborated with Owens on a version of the latter man’s early ’70s non-hit “Streets of Bakersfield,” and after Owens died, he recorded an entire album of his songs, Dwight Sings Buck. Even today, the Bakersfield sound is at the core of Yoakam’s style, no matter how many weird turns his albums may take toward psychedelic rock or even punk-rock aggression, as on his 2012 version of “Dim Lights, Thick Smoke (and Loud, Loud Music),” a song also covered by the Flying Burrito Brothers, Marty Stuart, the New Riders of the Purple Sage, the Beat Farmers, and many, many more.

The Bakersfield sound is country at its most hardcore; it’s music for drinking, crying into your beer, and maybe getting into a fight, because you’ve got to be back behind the wheel of your truck the next morning. Its very un-slickness is its greatest virtue; it’s no surprise at all that when punk rockers get a little gray at the temples and start listening to country, their ears cock in the direction of Bakersfield, not Nashville.