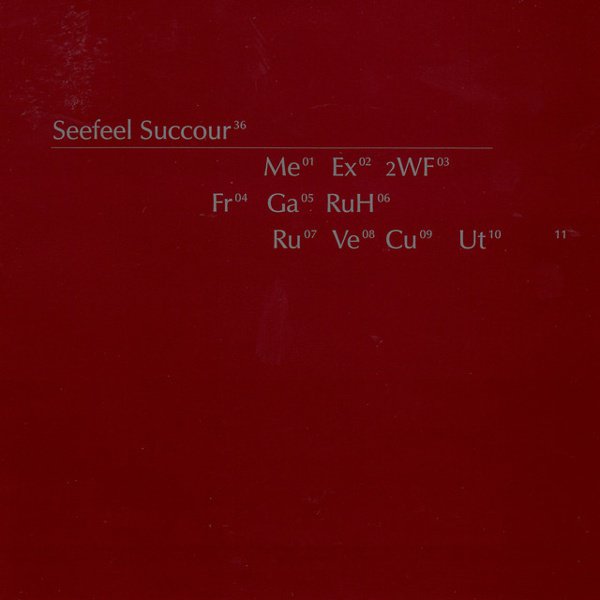

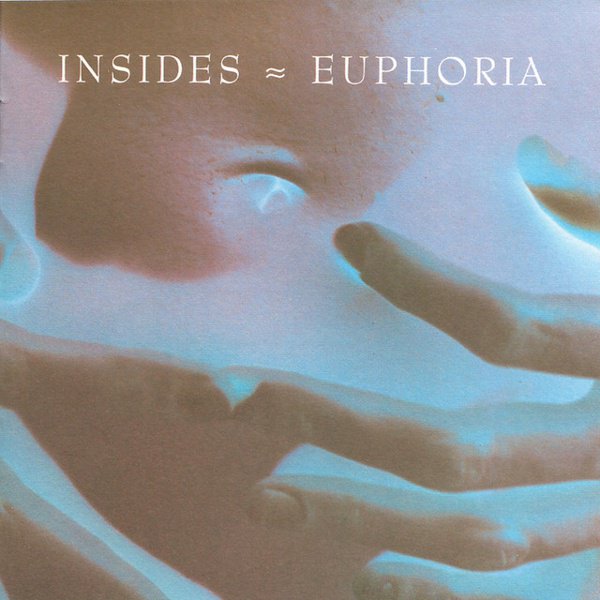

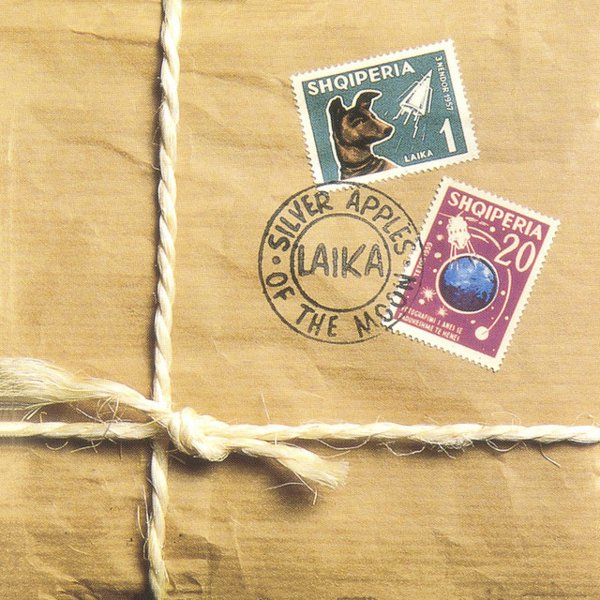

Post-rock, as a term with or without a hyphen, had occasionally appeared in print from the 1970s on, part of a speculation as to whatever might be next. But it wasn’t until UK critic Simon Reynolds, writing in Melody Maker and The Wire in 1994, created an initial codification of the term that it stuck and began to be used more broadly. Explained in part by Reynolds as the result of using ‘rock instrumentation for non-rock ends,’ he used it as a way to bring collective attention to a slew of predominantly UK acts, both new or formed of veterans, who steered clear of grunge and incipient Britpop in order to push experimental possibilities on various levels. While Talk Talk was retrospectively claimed for this wave, Reynolds cast his net wide to include groups ranging from the honed electronic specificity of Insides to the explosive collages of Disco Inferno, from the austere murk of Main to the mesmerizing metapop of Laika. Other acts of note Reynolds flagged included the many projects of Kevin Martin and Mick Harris and various bands and musicians from the US and elsewhere.

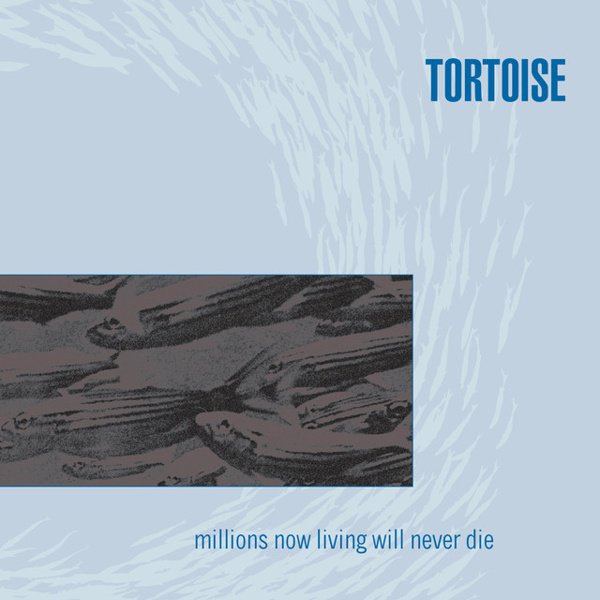

However, it was the legacy of one US act in particular Reynolds didn’t name, Slint, which ended up being the determining factor in how post-rock would eventually be codified and understood more broadly. Like Talk Talk they’d released a crowning achievement of an album in 1991 while also breaking up, with their influence felt both via various hometown acts in Louisville and in what became a well-known Chicago scene in particular thanks to Tortoise. With that as background, and with the term post-rock starting to shift towards describing often predominantly instrumental music, with the word ‘cinematic’ being used more than once, it was the success of Montreal’s Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Glasgow’s Mogwai and Reykjavik’s Sigur Rós towards the end of the 1990s which became the clear basis for the term being used as a reference point more widely. Vocals could be spoken-word, sung in non-English or even not a language at all, and unexpected instrumentation played further parts, but it was the sense of a big, epic-scaled sound, not so much post-rock as one carefully shaped extreme of rock, which proved to be the common throughline. By the time Explosions in the Sky began further popularizing this approach in a new millennium, the original Reynolds formulation and intent had long been left behind.