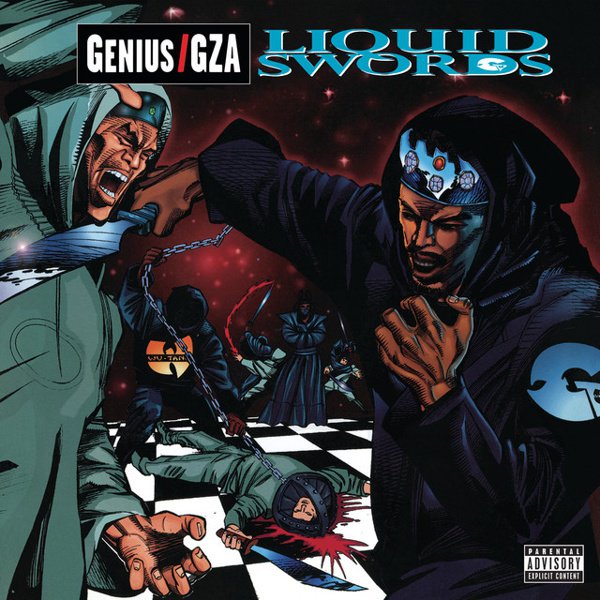

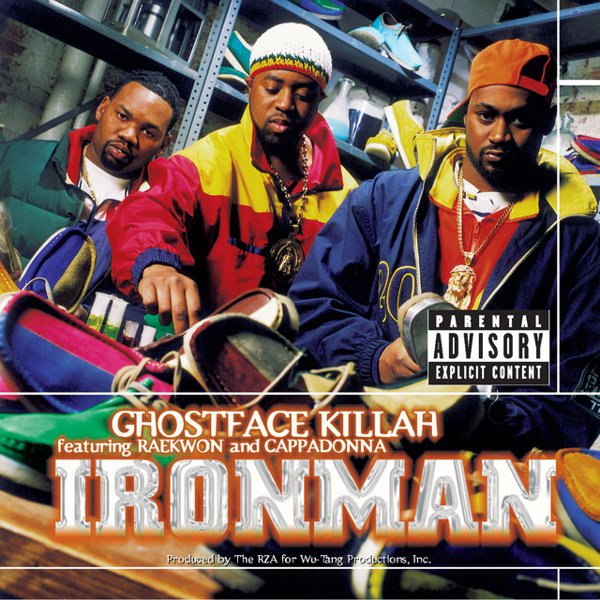

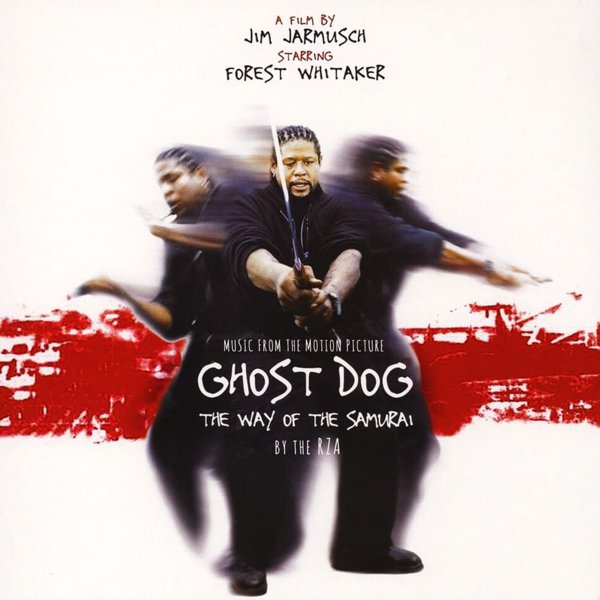

It’s wild when you think about it: there were nine members of the Wu-Tang Clan as they existed in 1993, and we got good-to-legendary albums out of eight of them. (No hard feelings, U-God.) Many of them were shepherded into existence by the RZA, the crew’s production sifu and philosophical center; just as many were collaborative beats-by-committee jobs that felt just as broad-scope in their ensemble casts as the pure, original vision of 36 Chambers. And this was by design: from the moment Loud signed the Wu-Tang, RZA had it written into their contract that each member could negotiate with any label they wanted when it came time to put out their solo releases. With RZA executive-producing it all, he actually positioned himself above the labels, treating them practically as a sort of middleman afterthought (quick, which label did Ironman or Liquid Swords come out on?) with corporate machinations proving subservient to the artists’ collective visions. The 36th Chamber of Shaolin was all about spreading the doctrine to a world outside Shaolin temple walls, and the Wu embodied that principle masterfully.

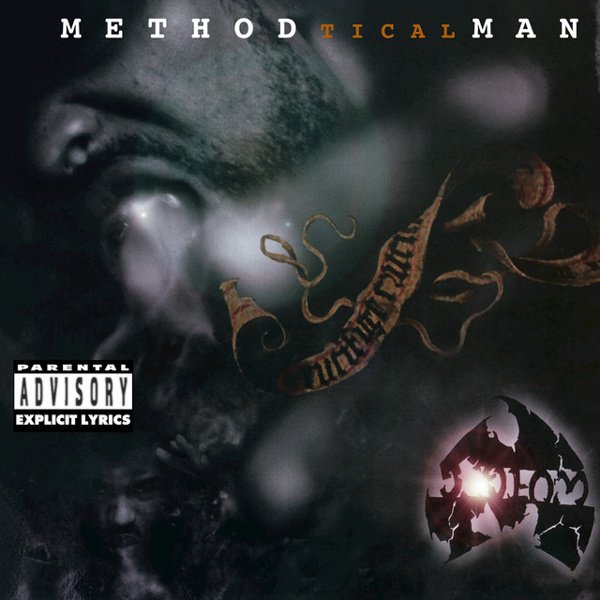

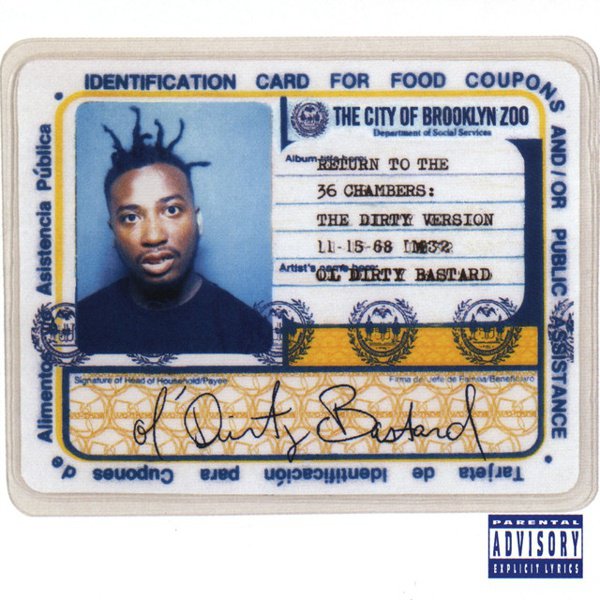

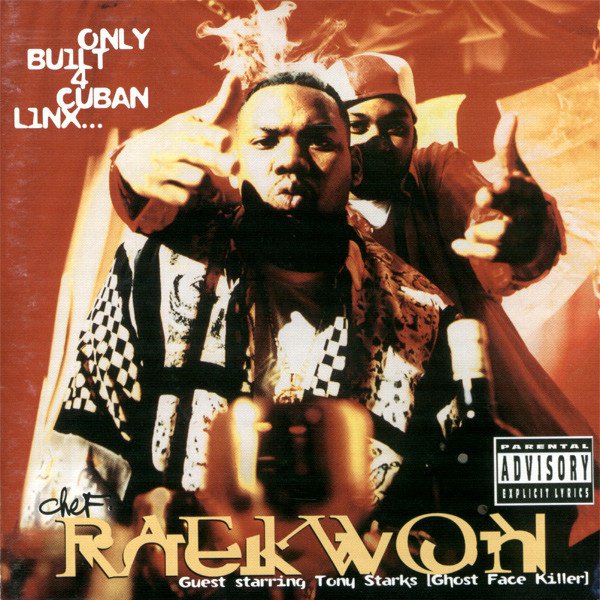

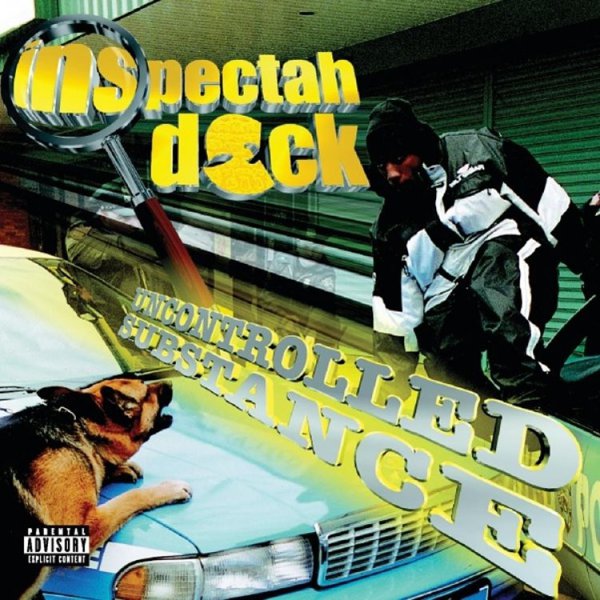

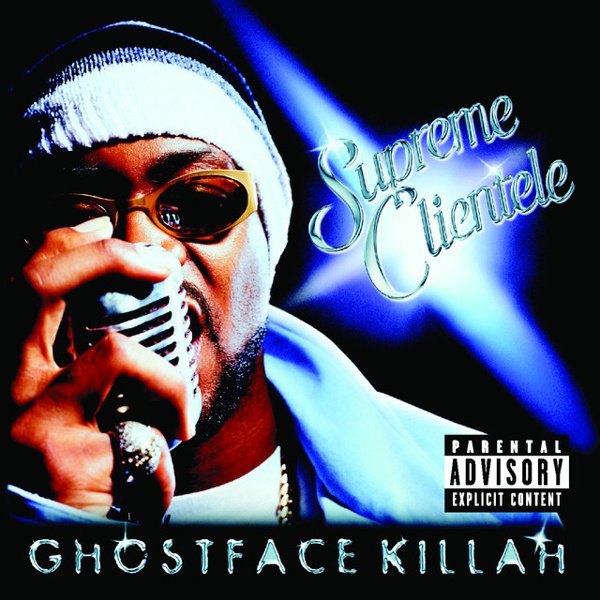

The bigger-picture miracle of this in an artistic sense is that the Wu-Tang brand was applicable to such a wide range of flows, lyrical approaches, and storytelling styles. The RZA could be the unifying factor as a producer on that first wave of solo joints, but you could still get everything from straightforward taped-knuckle shit-talk (Method Man) to Goines-meets-Scorsese tales of organized crime (Raekwon) to untethered, diabolical sing-song mindfuckery (Ol’ Dirty Bastard) to clinically intricate focused intensity (GZA) to some aggregate by-our-powers-combined embodiment of all those things (Ghostface Killah). And with even the less-hyped members like Inspectah Deck and Masta Killa, you have MCs who can carry a record better than many of their East Coast late ’90s/early ’00s peers. While the solo Wu records have tapered off recently — with the exception of extended family member Killah Priest’s remarkable dawn-of-the-’20s run, at least — there’s still more than enough depth in the catalogue to justify their rep as far more than just a product of oldhead nostalgia.