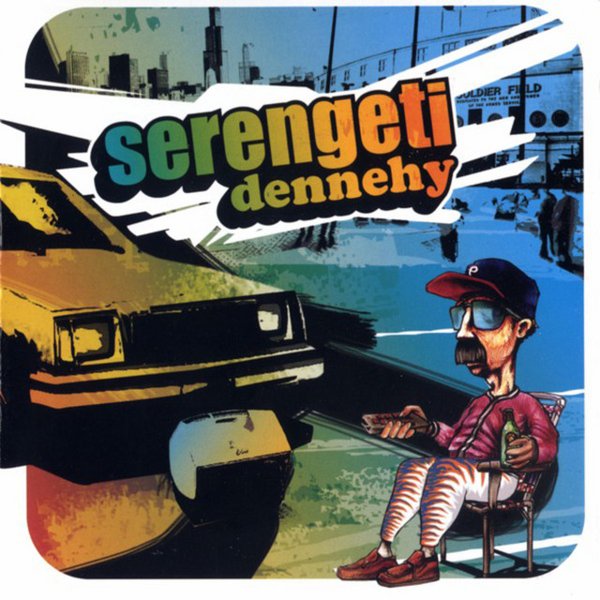

The rap alter ego is nothing new in hip-hop: MF DOOM and Kool Keith careened through a portfolio of them in order to draw out different narratives and perspectives to their rhymes, Shock G conjured up Humpty Hump as a P-Funk-esque raconteur hypeman who was every bit as tight on the mic as his “main” identity, and there were even early harbingers in hip-hop Year Zero 1973 when Last Poets member Jalal Mansur Nuriddin went incognito as Lightnin’ Rod to record the legendary proto-rap classic crime yarn Hustlers Convention. But there’s never been a persona quite like Kenny Dennis. Concocted by Chicago rapper Serengeti (nee David Cohn) and given his first major place of honor as the featured character on the cover and title cut of his 2006 album Dennehy, Kenny is a fascinating study in how a detail-focused rapper with a deep interest in the inner lives of the people he writes about can develop a fictional presence into someone that feels deeply resonant, even real.

This isn’t rare territory for Geti. 2011’s Family&Friends, which is worth checking out first if you haven’t gotten familiar, is a prime example of how he can weave a bunch of regional tics, pop culture references, and personal travails into a vivid portrait that transcends Type Of Guy rigidity to depict people far more complicated than surface details might depict. And his storytelling is often a bit more impressionistic than expositional — listeners might glean less than half of what a character’s really thinking, but they’ll also have a clear picture of where it’s all happening, how it all feels, and what details at the margins wind up lingering after the fact. (If he really wanted to tell a compelling MMA story, Bennie Safdie should’ve adapted “The Whip” instead of John Hyams’ Mark Kerr doc The Smashing Machine.) He’s also got a voice that gravitates towards midtempo mellowness, but is ready to switch things up at just the right time into fast-rap overload or emotional tumult — a versatility that’s necessary when you want to draw out the nuances of a whole cast of characters, like a novelist who has to double as a voice actor.

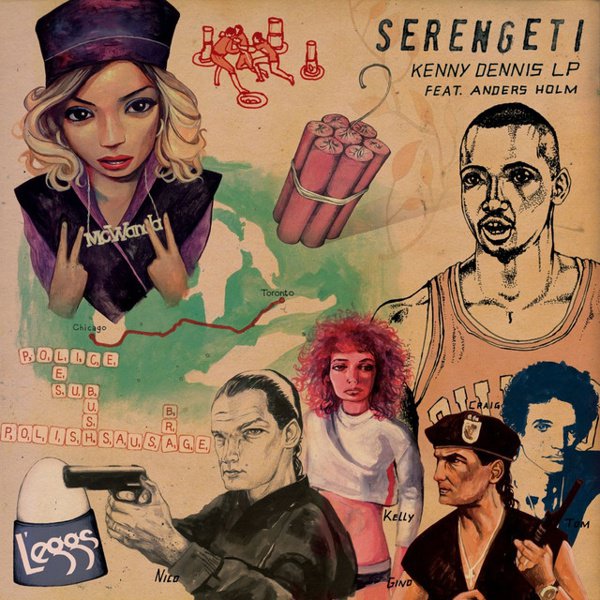

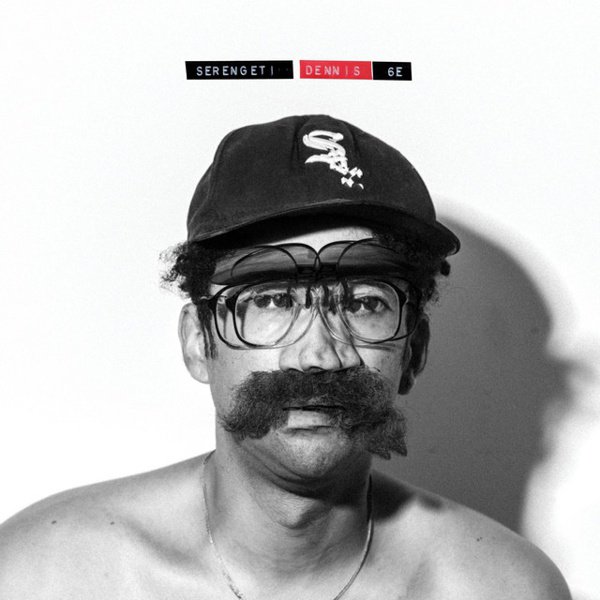

Still, there’s something about Kenny Dennis that stands out amongst Geti’s characters, and not just because the mustachioed Bears superfan is a popular fan favorite. Kenny is at once a cross-cultural caricature and a real-seeming individual: a working-class white guy character portrayed by a Black rapper a generation younger than him, but also a hometown-signifying fixture in his peripheral vision with his own familiar struggles and sources of empathy. They share a few obsessions and preoccupations — softball, martial arts, blue-collar labor — to ground the character in Geti’s own experience. (He’s often compared going into Kenny Dennis Mode to becoming The Hulk, just something he keeps under the surface.) But Kenny also expands Geti’s own imagination into the shoes of someone with a different, more outgoing social world. Kenny’s portrayals are often comedic in a way that hints at Serengeti’s own self-effacing tendencies; there’s something very Second City self-aware about the heaviness of Kenny’s accent and his fixation on the past glories of Ditka and Jordan as a way of trying to hang on to memories of a specific place in the world as you first really remembered and loved it.

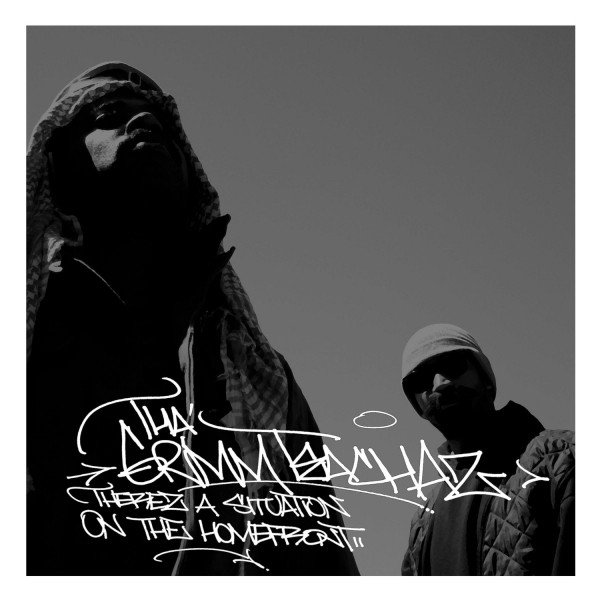

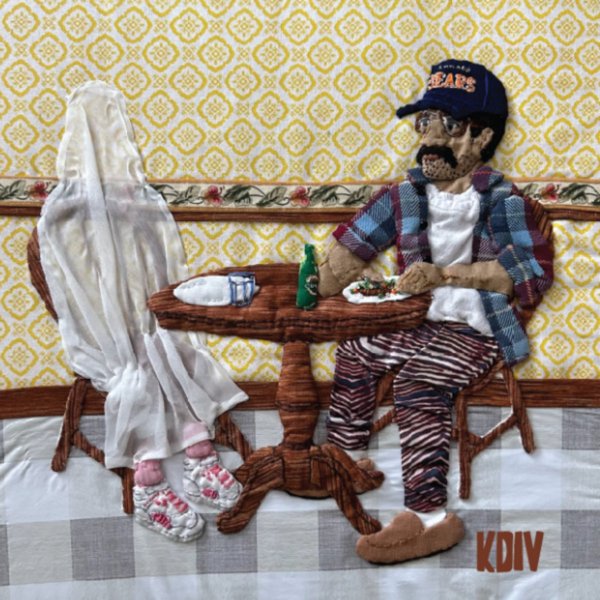

But the further Serengeti went into the theoretical inner reaches of Kenny’s personality, the more it became apparent that there was a deeper story to be told. “Dennehy” wasn’t just someone rapping in character, it was developing a character who could rap — someone with a different voice and flow to him, an exercise in pushing past Geti’s usual parameters into the flow of someone raspier, louder, and more prone to getting stuck in the same handful of self-defining reference points as a way to stave off a succession of personality crises. Kenny’s backstory is both absurd and tragic, a sort of dark comedy a’la Fear of a Black Hat through the Coen Brothers: an aspiring ‘90s rap star who blew it because he couldn’t brush off a slight from NBA star and Fu-Schnickens guest Shaquille O’Neal, he is left to spend the ensuing years constantly wondering what if as he marinates in his squandered potential between paeans to Andre Dawson and Polish sausage. The only things that keep him going are a succession of midlife-crisis reinvention efforts and a Wife Guy energy so powerful that he keeps manifesting his partner Jueles into his life even though she’s been out of it for decades. It’s both as bleaky comedic and uncomfortably sad as it sounds.

What Kenny Dennis isn’t, however, is a loser. He’s a reflection of a certain corner of the multicultural urban world in flux and crisis, an aging head whose struggles to weigh past triumphs against future potential lead him down some unlikely paths. DOOM is a noticeable lyrical influence on Serengeti’s style, but it also recalls the kinds of characters you’d see populating a Jim Jarmusch film or a Carl Hiaasen novel, the kind of people who look like burnout losers or fuckup weirdos from the outside yet have an endless depth of both bravado and sorrow pulling them through the world.