For a good stretch of the peak CD era, it became not only fashionable but practically de rigueur for a previous generation’s most-revered artists to earn an all-star tribute record. With the reissue boom that the record industry benefited from — thanks to a potent combination of nostalgia and a new format to buy all those old records on — the idea of older pop music as a renewable resource started to cut into the old saw that you’re supposed to rebel against the music of your parents’ generation. So the tribute comp was a surefire way to keep those back catalogues relevant: sure, these are old songs, but if R.E.M. or Sheryl Crow or Tom Waits can make them sound like they belong in their own contemporary catalogues, then maybe they can pique some interest in the original records those songs came from, too. It was good for business, good for canon-building, good for rediscovering semi-forgotten yet low-key influential artists, and good for the occasional bizarre novelty. (Ever wanted to hear your favorite alt-rockers play your favorite James Bond or Saturday Morning Cartoon themes?) And since so many of them were also tied into charitable interests — think the Sweet Relief series, which started off with an alt-rock tribute to MS-stricken singer-songwriter Victoria Williams and has grown into a long-running nonprofit to aid ailing musicians — they were often for a good cause as well.

The catch is that a legitimately good tribute compilation is tricky to pull off. If an artist is too revered, it might be hard for a dozen or so disparate artists to fully live up to the original work, and there are almost always at least a couple tracks that will have fans of the honored musician wrinkling their noses in disgust. If, instead, the artist is cast as a guilty pleasure or “secretly cool,” it might be difficult to cut through the outer layer of potential irony to get to the actual resonance underneath. Stylistic detours and genre-flouting crossovers could sound too detached from the spirit of the original song. There’s also the legal, contract-juggling aspect involved in attempting to even wrangle all these different artists from different labels into the same project in the first place. And, at worst, it could just come across like victory-lap karaoke for artists who’ve long since grown stale in the spotlight, just another way for omnipresent monocultural acts to work their way deeper into diminishing-returns ubiquity.

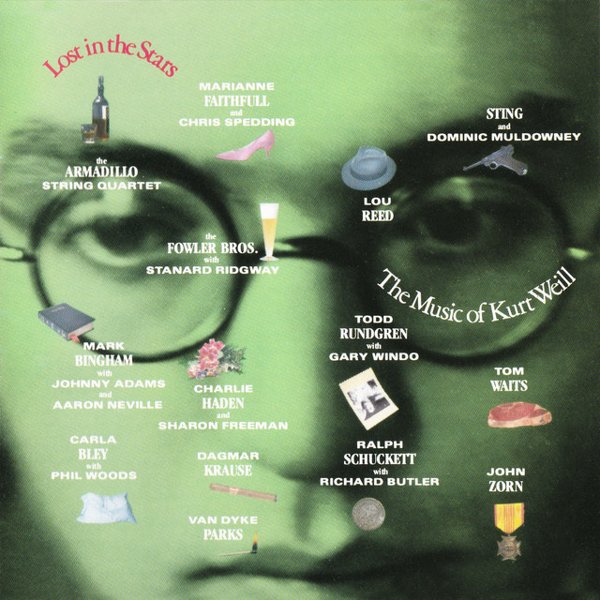

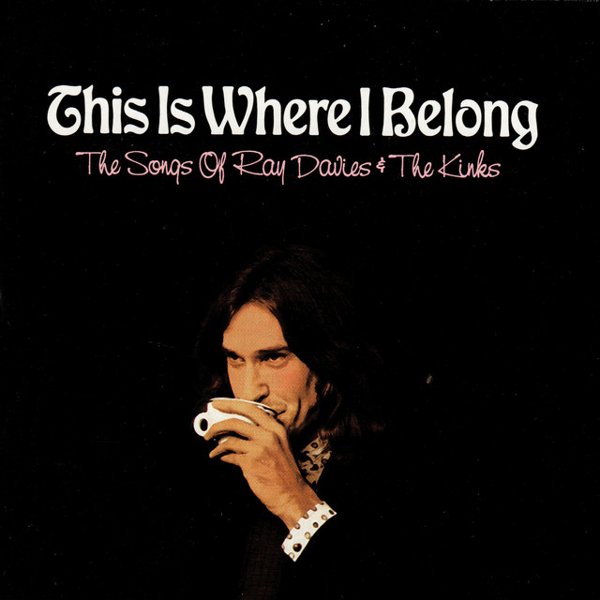

So what does it take to create a successful tribute compilation? It helps to go back and consult two pivotal entities that helped fuel the boom throughout the CD era. One was an individual, the tastemaker producer Hal Willner, who knew a thing or two about surprising musical juxtapositions as the producer of late ‘80s genre-bending cult TV show Night Music. In 1981, he produced a tribute album, Amarcord Nino Rota, that paid homage to the composer’s scores for the films of Federico Fellini, focused primarily on an ensemble of jazz musicians (and a cameo by Debbie Harry and Chris Stein of Blondie). That was followed by That’s The Way I Feel Now: A Tribute to Thelonious Monk in ‘84, which expanded its contributor purview deeper into multi-genre rock and pop — just in case there was a crossover audience between Carla Bley and Peter Frampton — to ambitious if often disorienting effect. It was with 1985’s Lost in the Stars: The Music of Kurt Weill, a critically esteemed album that finished the ‘85 Pazz & Jop Poll at #17 (a notch ahead of Kate Bush’s Hounds of Love), that used its star-packed roster and exhaustively informative liner notes to create a cohesive yet eclectic overview of its subject’s wide and still-relevant cultural impact.

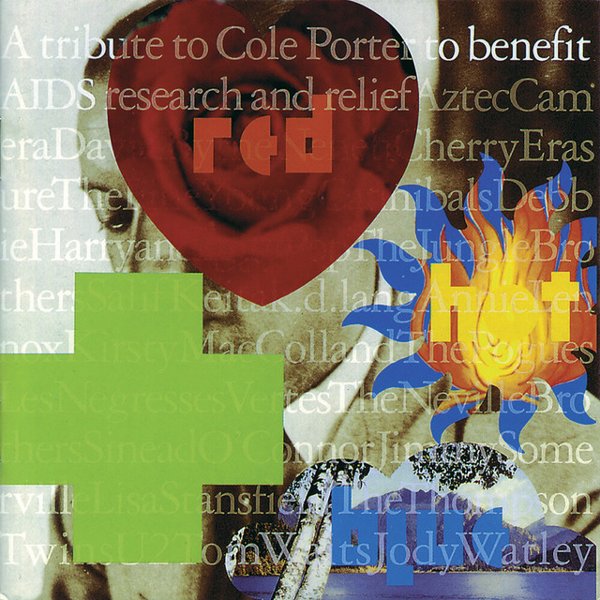

The other, the Red Hot Organization, emerged at the turn of the ‘90s as a sort of all-star charity awareness effort at fighting the AIDS epidemic, kicking off with a daring, queer-friendly take on the Cole Porter catalog that soon expanded into nearly every genre imaginable, whether it was dedicated to individual artists (Red Hot + Riot: the Music and the Spirit of Fela Kuti; Red Hot + Rhapsody: The Gershwin Groove), assembling thematic overviews of pivotal scenes (the mid ‘90s hip-hop confab America Is Dying Slowly; 2009’s indie-folk zeitgeist snapshot Dark Was the Night), or just getting as many artists together as possible to make an important statement (2024’s trans-rights collection Transa). Give the entire Red Hot catalogue a front-to-back listen and you’ll probably wind up with a wider breadth of musical awareness and knowledge of history than your typical record store clerk.

In the streaming era, the tribute comp has only become more commonplace. There will always be new generations of artists reviving the old ones, en route to becoming the old generations themselves, and the record labels to accommodate a loose context for those revivals. But one thing that these compilations offered in the CD era and needs preservation now is context: not just a playlist stringing together a bunch of cover songs, but the framing around it, a dive into the history and genealogy of the music and the artists being paid tribute. The best tribute compilations aren’t just vibes, they’re chronicles of pop’s evolution, embodying the unexpected yet successful detours that the lineage of our favorite music can take as a living document.