In the mid-20th century, a wave of Jamaican immigrants moved to England, settling in significant numbers in South London, Birmingham, and Bristol. They brought with them various aspects of Caribbean culture, including foodways and a distinctive patois – and, perhaps most impactfully from a cultural perspective, their music. In the 1950s this meant calypso and mento, but back in Jamaica a fusion of local musical styles and American R&B would soon result in a new style of dance music called ska, which would eventually slow into rock steady, and then slow and deepen further to become reggae. By the late 1960s reggae had become the predominant popular music style in Jamaica – and in Britain’s Jamaican diaspora.

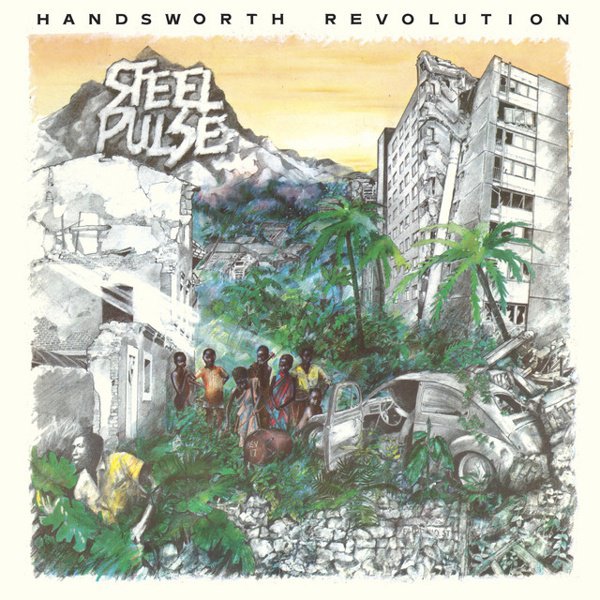

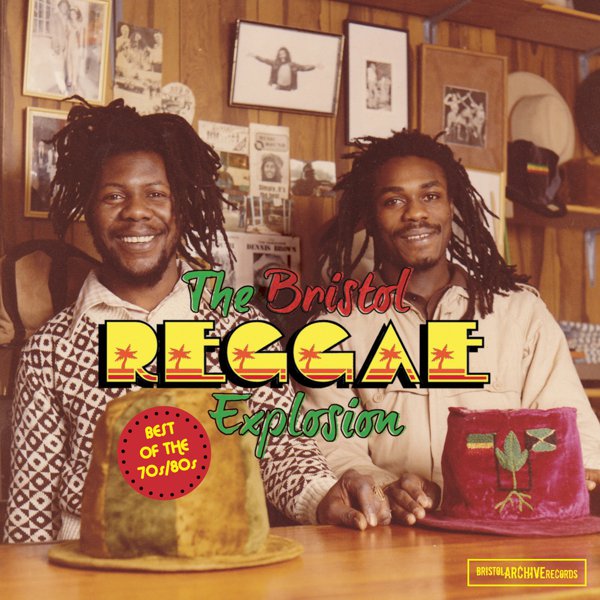

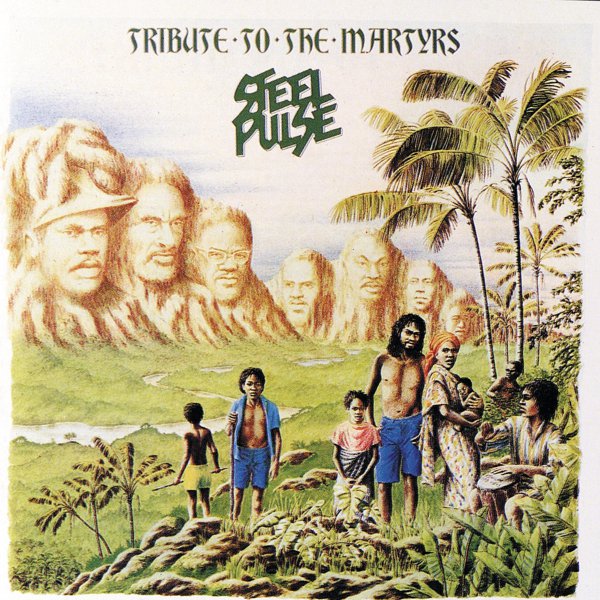

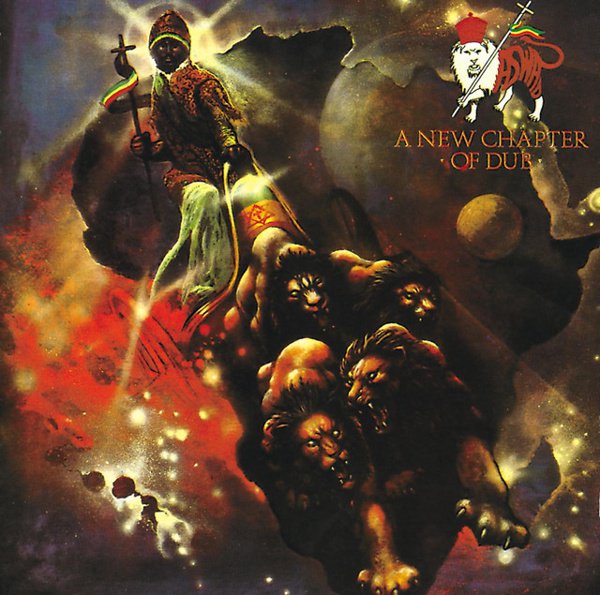

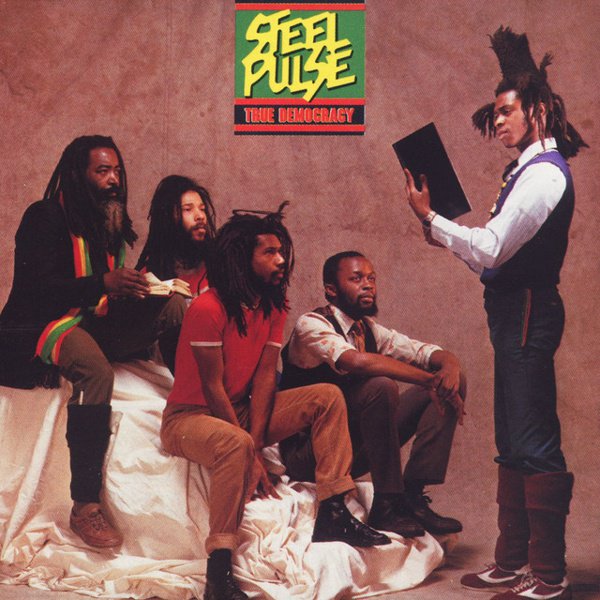

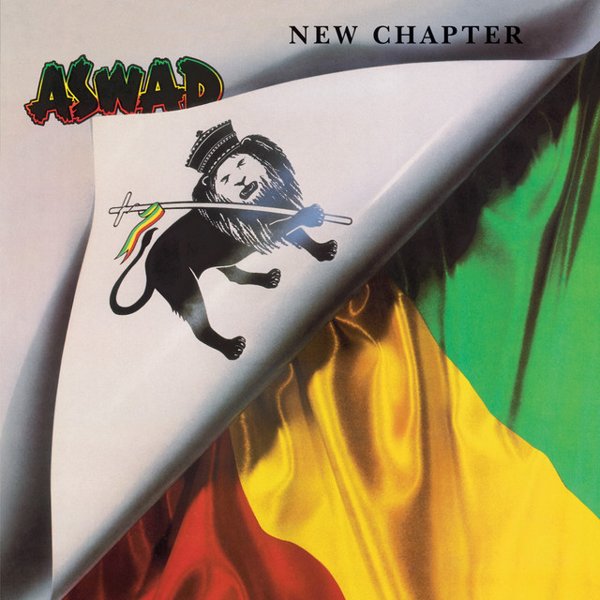

In the West Indian enclaves of Brixton in South London, the Handsworth area of Birmingham, and the Black neighborhoods of Bristol, reggae took hold quickly and bands began to spring up. By the mid-1970s, artists like Steel Pulse, Aswad, Matumbi, and Misty in Roots were established and were soon playing to large audiences of expatriate Jamaicans.

When punk rock erupted in England a few years later, the country’s various reggae scenes were already well established – and found an enthusiastic audience among the young punks who were smashing up the musical conventions of rock and pop music. It was an odd marriage: punk was an overwhelmingly White phenomenon, one characterized by calls for anarchy and predictions of “no future,” while the reggae music of the period was dominated by themes of “roots and culture” – invocations of millenarian Rastafarian religion and calls for political reform. But the countercultural messages and the racial pride and defiance of British reggae artists struck a chord with young punk rockers, and soon bands like the Clash and the Ruts were incorporating reggae beats and even covering roots reggae songs (the Clash included a version of Junior Murvin’s “Police and Thieves” on their debut album, reportedly to the original artist’s consternation).

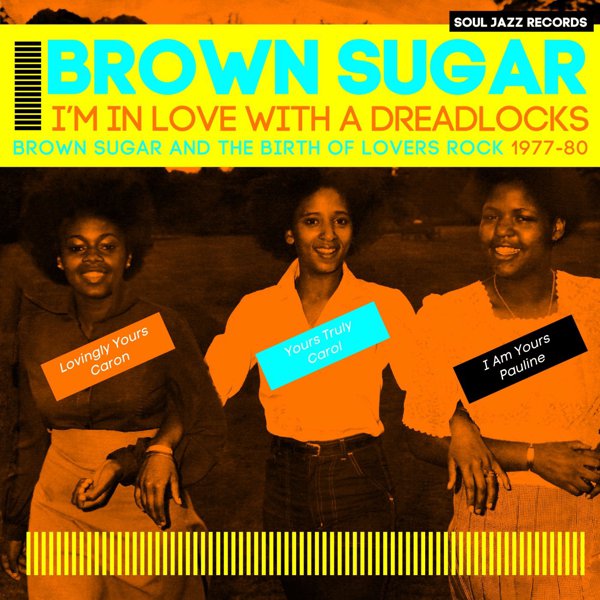

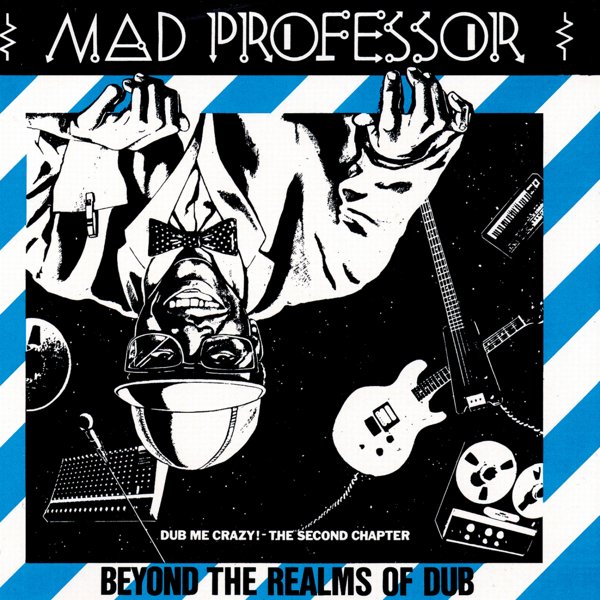

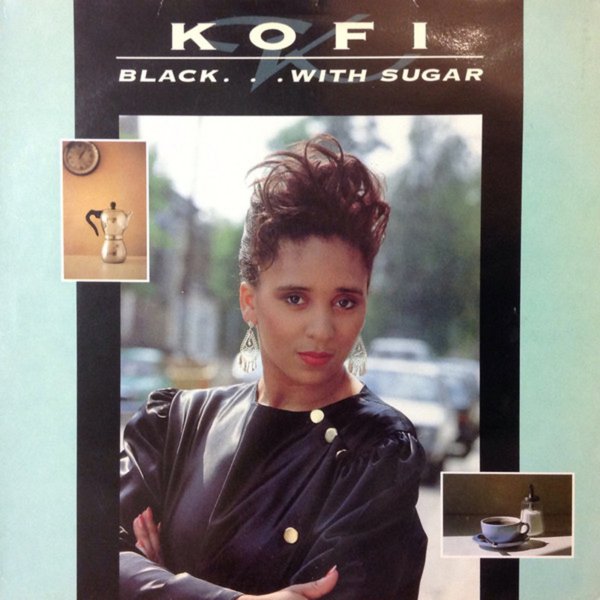

At the same time that political and spiritual reggae was growing in popularity in the UK, another subgenre was taking root as well. A smoother, more romantic reggae style that would come to be called “lovers rock” emerged in London, championed by star producer (and Matumbi bassist) Dennis Bovell and up-and-comer Neil “Mad Professor” Fraser. Fraser, especially, would be a major figure in both defining and refining the lovers rock genre, releasing groundbreaking albums by smooth crooners like Sandra Cross and Kofi in the 1980s. While lovers rock, as its name suggests, tended to focus on romantic lyrics, the songs were not always apolitical; the trio Brown Sugar had a major hit with the defiant “I’m in Love with a Dreadlocks,” for example, and their “Black Pride” took a similarly bold social stance.

In the years since the roots and lovers period, British reggae has continued to spread and develop; the London-based Fashion Records label brought dancehall reggae to the island in the 1990s; the emergence of jungle and drum’n’bass in London’s 1990s underground dance clubs was a direct outgrowth of the country’s fertile reggae culture. Kingston-style open-air sound system dances continue to be popular in England’s Black population centers, and even as Jamaica itself seems to have left roots-and-culture reggae behind in favor of the harder dancehall and bashment styles, the music continues to thrive in the major cities of Jamaica’s former colonial ruler.