The richness of African musical styles is matched only by the continent’s enormous variety of musical instruments. While most instruments in Africa serve roles that go beyond simple entertainment, stringed instruments in particular have long played a role in maintaining oral traditions, preserving genealogies, and accompanying religious and ritual ceremonies. Although there are hundreds of different types of stringed instruments across the continent, they can broadly be divided into into bowed (fiddles), plucked (harps, lutes, zithers, harp-lutes, harp-zithers) and beaten (musical bows, earth-bows) types.

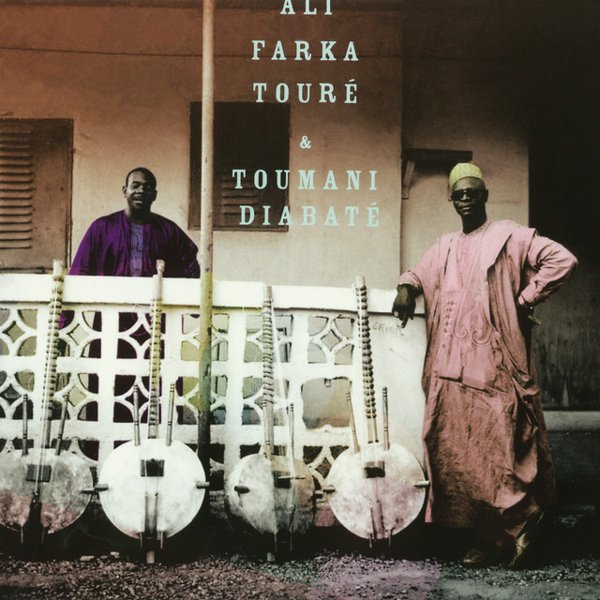

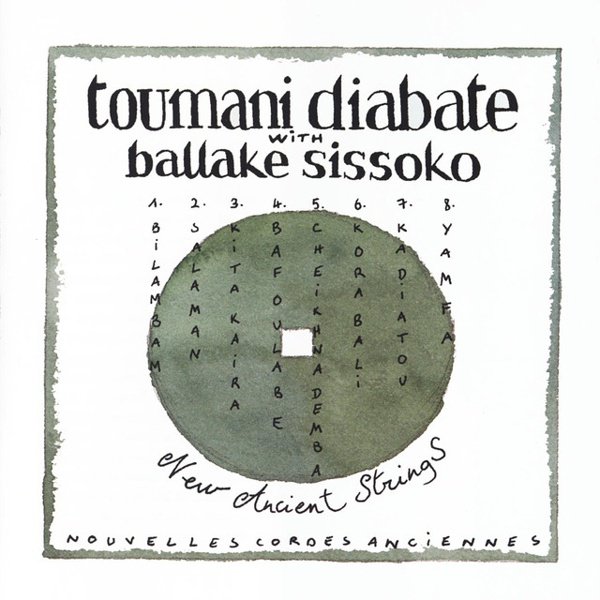

The kora, the long-necked harp lute of the Mandinka people, is by far the most well known in the West, and since the 1970s its ethereal sound has conquered the global stage. The instrument’s success is in large part due to Toumani Diabate and Ballake Sissoko’s beautiful album Ancient Strings, which helped the kora break down musical borders and span new territories, whilst at the same time remaining rooted in tradition. Kora players have always drawn on tradition, but each generation has pushed boundaries and challenged norms, changing the instrument’s style and sound over the years. While this has eroded some of the kora’s more traditional aspects, it has arguably ensured its survival and enduring popularity. In Senegal, for example, Noumoucounda Cissoko, who comes from a long line of griots but is also a pillar of Dakar’s hip hop scene, has popularized the sound of the kora in the pop and rap landscapes.

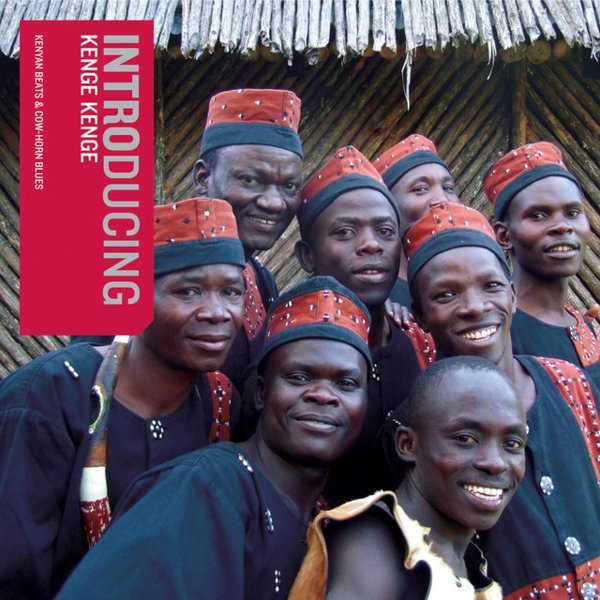

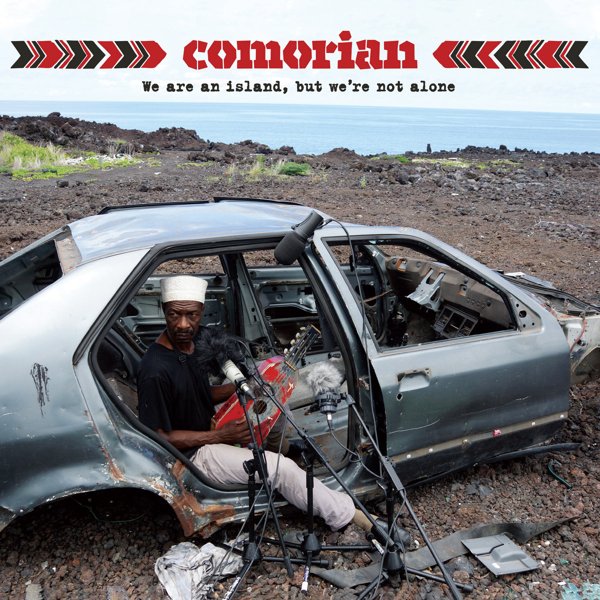

But the kora is only one of thousands of African stringed instruments: many have disappeared or are disappearing along with their masters; other instruments are still commonly used in traditional music or religious ceremonies; some traditional instruments, like the kora, are being taken up by younger generations, and entering the popular music spheres. The orutu, for example, is a one-stringed vertical fiddle of the Luo community from Western Kenya that was almost lost because of Western missionaries’ suppression of traditional African cultures. But thanks to several young Kenyan musicians, the small fiddle is undergoing a renaissance of sorts.

The orutu is one of many bowed string instruments played across Africa. By far the most common is the goje or “Hausa Violin” and its many variations, a one or two stringed fiddle traditionally tied to pre-Islamic rituals in the Sahel and Sudan. This instrument can sometimes imitate language, for example among the Tamashek nomads of Niger and the Yoruba in Nigeria, assuming an almost human role in the band. Similarly, in Ethiopia, the masenqo played by the azmaris has been used to accompany storytellers. In the Sahara Tuareg women traditionally accompany the men’s poetry and song with their imzad, a single-stringed fiddle.

Plucked instruments include the elegant West African kora, which is classified as a harp lute and consists of a sound-box (a large half-calabash over which a skin is stretched), a large bridge, and 21 strings, which are anchored to the bottom of the long neck with a metal ring. It is thought to have originated in around the Gambia River valley, and is currently played in Gambia, Senegal, Mali, Guinea, and Burkina Faso; as far back as the 1300s scholar and explorer Ibn Battuta described seeing a similar instrument in Mali. Kora players have traditionally come from jali families of the Mandinka tribes and function as historians and storytellers, passing down their skill down through the generations. There are several kora virtuosi, all descendants from important kora-playing families, but Toumani Diabaté is widely recognized as one of the world’s best kora players. His father Sidiki Diabaté recorded the first kora album Ancient Strings in 1970, and their family oral tradition says they come from 70 generations of musicians.

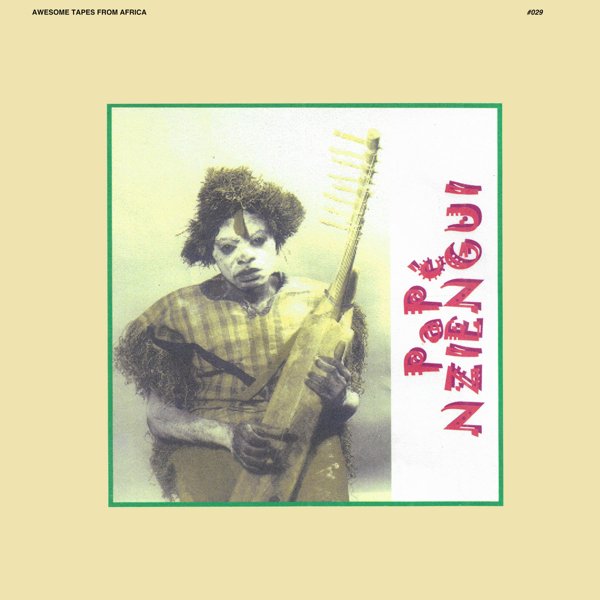

Other types of harps are common across certain regions of Africa, especially the belt running from Uganda to Mauritania, just north of the Equator. These include the ennanga of Uganda; the bolon, a large, three-stringed harp from Mali and Guinea that used to be played during military or hunting ceremonies; the kinde harp from the Lake Chad region; and the sacred bwiti harp, played and worshiped by a secret society for the men of the Bahumbu tribe in Gabon. While still being very much tied to tradition, the bwiti harp is one of those instruments that has found its way into modern genres, thanks especially to bwiti master Papé Nziengui, who fused the bwiti’s traditional sound with electric guitars, backing vocals, and layers of synths, creating a “postmodern Gabonese sound.”

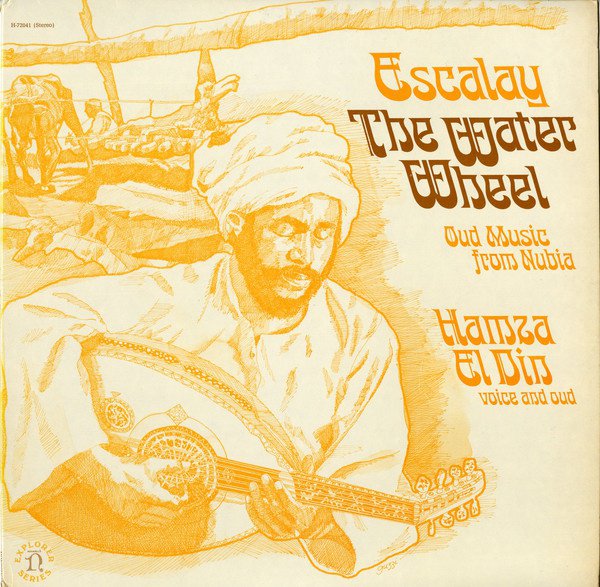

Lutes are found in many different parts of Africa. It is thought that West African plucked lutes may have originated in ancient Egypt, and the akonting (from Senegal, Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau), the ngoni (from Mali), and khalam or xalam (from Senegal) may be an ancestors of the banjo, transported to the Americas through the slave trade. Like the kora, the ngoni has played an important role in preserving histories in parts of West Africa. Ngoni master Bassekou Kouyaté for example comes from a lineage of ngoni players that dates back hundreds of years, and his music has evolved from faithfully traditional arrangements to more contemporary sounds, with albums such as the powerful rock infused Ba Power.

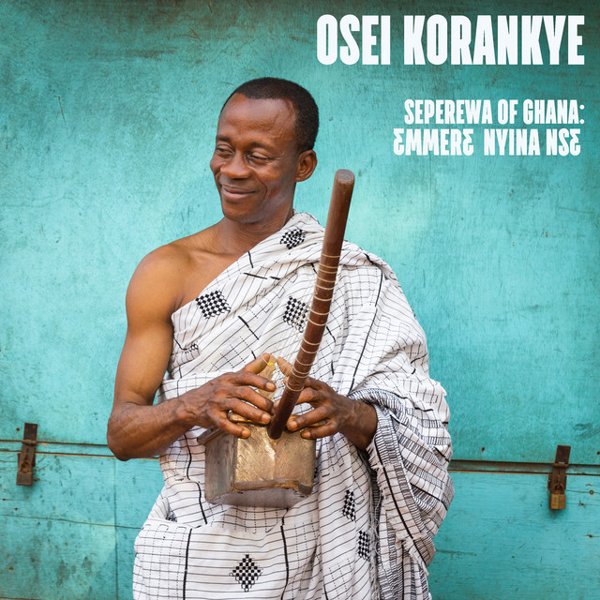

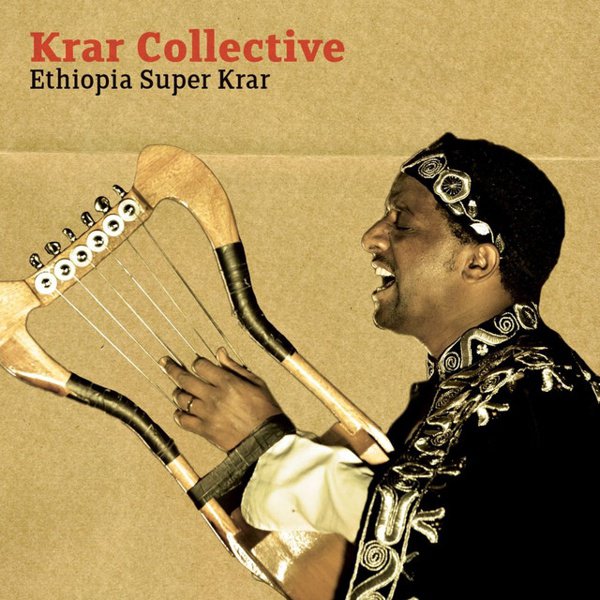

Lyres are most typical of northeastern Africa, both as traditional instruments and in their updated, “modernized” versions. The krar (a five-or-six stringed bowl-shaped lyre tuned to the pentatonic scale) for example is still commonly played by traditional storytellers, and the 1960s sound of legendary singer and krar player Asnakech Worku remains wildly popular today. At the same time groups such as Krar Collective are offering up mind-blowing Ethiopian grooves with their electrified krars, and cutting edge electronic producers like Endeguena Mulu, aka Ethiopian Records, are “chopping it up” and including it in their compositions.

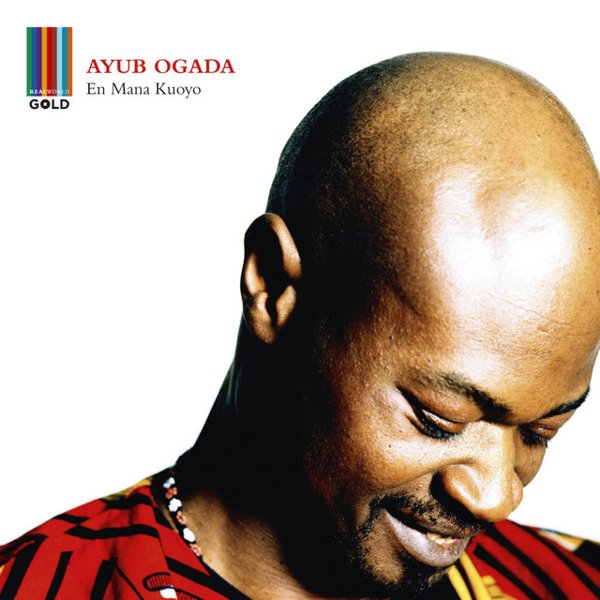

The national instrument of the Baganda people of Uganda is the endongo, an increasingly rare lyre made with the skin of either a monitor lizard or ant lizard; in Kenya, one of the most popular traditional instruments is the eight-stringed plucked bowl lyre known as the nyatiti, made famous across the world by the delicate, transportive music of Ayub Ogada. The Luo musician is widely regarded as one of Kenya’s greatest artists, and was “discovered” by Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios while busking in the London underground. Following in Ayub’s footsteps, Makadem has emerged as the Nyatiti’s newest “master”, even though his approach is very different: though rooted in the refined and rich Nyatiti sound, his music blends Ohangla rhythms with benga, hip-hop, funk, and Afro-pop grooves.

Zithers are another instrument with plucked strings but, unlike the lute, they have no neck. Different types of zither can be found in various parts of Africa, but are by far most common in Madagascar, where the valiha tube zither, constructed with 21 and 24 strings made by unwound bicycle brake cable tied through nails, running the length of a long bamboo pole, is considered a national instrument. Initially played to invoke the ancestors, the valiha is now played across musical genres, either as a lead instrument, with its bright, plucked sounds, or as a trancy drone tone. The marovany is another type of Malagasy zither, but it is box shaped rather than being long, and is traditionally used in religious rituals.

Many stringed instruments across Africa play specific social roles: some serve ritual or religious purposes, while others can only be played by people of a certain age, sex, or status. In the Luo community from Western Kenya for example only men are traditionally allowed to play the orutu, while among Moorish griots of Mauritania the ardine is only played by women.

But music is living and breathing, sounds are constantly evolving and traditions are being challenged. In Kenya Labdi Ommes has taken up the orutu, combining it with electronic music and jazz, and exposing a whole new generation to this traditional instrument. Sona Jobarteh, who was born into one of the five principal kora-playing griot families of West Africa, has broken with tradition to become the first woman to take up the instrument. And while some ancient string instruments have been lost, others are being “rediscovered” by younger generations, modernized and incorporated into different genres.