Chicago blues is literally the sound of the Great Migration. As vast numbers of Black Americans rolled north beginning in the 1910s, they brought their musical traditions with them, but updated them to suit their new circumstances. The blues was a way of chronicling Black life, so when that life changed, the lyrics and ultimately the sound changed, too. Chicago blues, with its clanging electric guitars and shrieking, distorted harmonica, is a perfect example of what Luigi Rossolo wrote about in his famous 1913 essay The Art of Noise:

“Nowadays musical art aims at the shrillest, strangest and most dissonant amalgams of sound. Thus we are approaching noise-sound. This revolution of music is paralleled by the increasing proliferation of machinery sharing in human labor. In the pounding atmosphere of great cities…machines create today such a large number of varied noises that pure sound, with its littleness and its monotony, now fails to arouse any emotion. To excite our sensibility, music has developed into a search for a more complex polyphony and a greater variety of instrumental tones and coloring. It has tried to obtain the most complex succession of dissonant chords, thus preparing the ground for Musical Noise.”

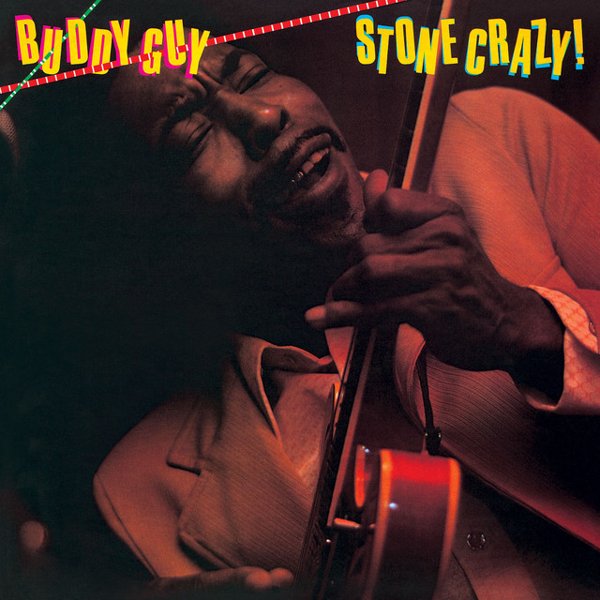

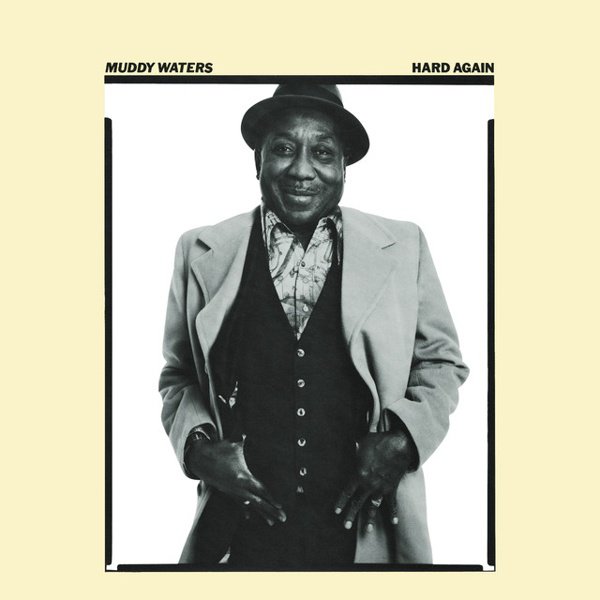

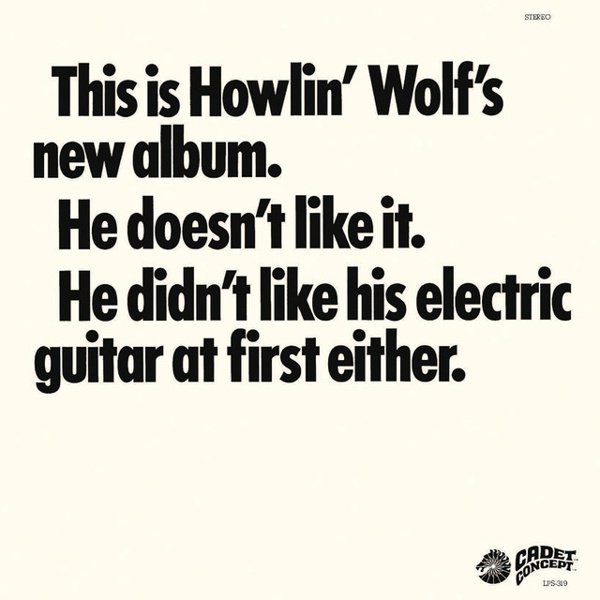

The city’s South Side in particular was the cradle of the urban blues. Players would arrive from Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee or Louisiana, and get their start playing house parties or the outdoor market on Maxwell Street. Eventually, they might be able to get gigs playing in the city’s bars, and as with Bakersfield country, the demands of the audience and the environment shaped the music. Sitting down with an acoustic guitar, plucking out simple country boogie rhythms, wasn’t going to get the job done, and Chicago blues became an electric — and amplified — music. Guitarists like Howlin’ Wolf’s secret weapon Hubert Sumlin, Jimmy Rogers from Muddy Waters’ band, and later Otis Rush, Buddy Guy and others, cranked up the volume, while Little Walter blasted listeners with a harmonica played directly into a hand-held microphone, creating waves of steely distortion. The lyrical tone of Chicago blues was different, too, often more sexually aggressive and bragging than that heard on the Delta. Tales of heartbreak and sorrow remained at the heart of the music, of course, but Waters’ songs like “Hoochie Coochie Man” and “I’m Ready” (“I’m drinkin’ TNT, I’m smokin’ dynamite/I hope some screwball start a fight”), and Howlin’ Wolf’s “Back Door Man” were soundtracks to urban life.

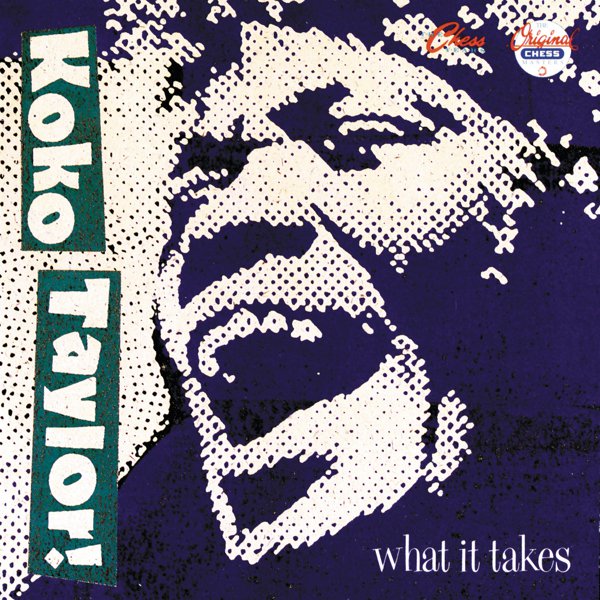

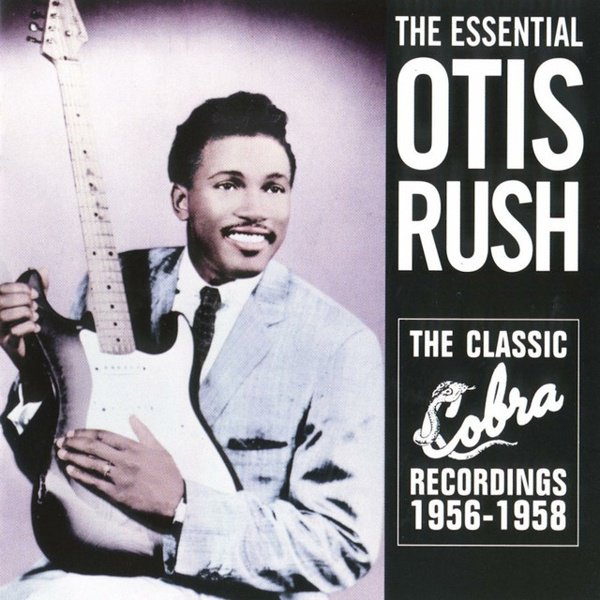

The music was documented by a variety of labels, including majors like Columbia and RCA Victor, but some of the most important were local indies like Chess, Delmark and Alligator. Chess’s roster included both Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, as well as Little Walter, Willie Dixon (who wrote songs for everyone), Buddy Guy, and performers who evolved the blues into rock ’n’ roll like Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley. When one considers not only the commercial impact of these artists’ original recordings, but their influence on everything that came after, it’s easy to argue that Chess Records was one of the most important record labels in history. Though smaller, Vee-Jay, Delmark and Cobra were also important, bringing the world John Lee Hooker, Magic Sam and Otis Rush, among many others, and Alligator Records, launched in the early 1970s specifically to release the music of Hound Dog Taylor, gradually became one of America’s best blues imprints.

At this point in history, Chicago blues is undoubtedly the sound most people think of when they think of blues, period; it has long since eclipsed the acoustic Mississippi Delta music that codified the form, and other styles — the one-chord droning vamps of the Mississippi hill country or the jazzier Texas blues — are regional styles mostly of interest to specialists. And the performers who made their mark during the heyday of Chicago blues, from the 1940s to the 1960s, were some of the greatest musicians America and the world have ever produced. These songs will be heard and sung, and influence subsequent generations, as long as music exists.