“Wouldn’t it be wild if we made our own record?”

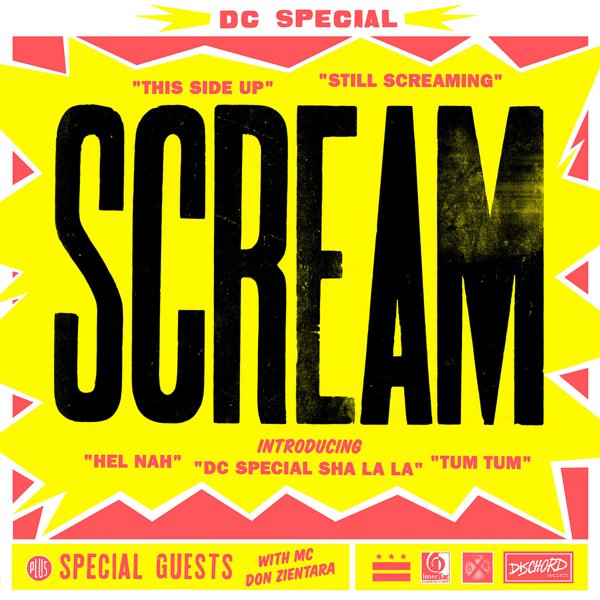

It was mid-1980, and the Teen Idles, a young hardcore band from Washington, D.C., had just returned from playing shows on the West Coast. As recounted in Dance of Days, Mark Andersen and Mark Jenkins’ definitive history of the city’s punk scene, the members were hanging out at Yesterday and Today, a local record shop they frequented, when one of them made this seemingly far-fetched suggestion. The store’s owner, Skip Groff, also a DIY label owner, informed them that their idea was actually very much within reach. Groff soon brought them to Inner Ear — a home studio that area engineer Don Zientara had set up in the basement of his Arlington, VA, home — to record and guided them through the vinyl-pressing process.

The Idles would soon decide to call it quits, but they followed through on the release anyway, coming up with a label name and, in December 1980, issuing their Minor Disturbance EP as Dischord No. 1.

“We felt like, well, this was really important for us and for our friends,” Teen Idles bassist Ian MacKaye told Tom Mullen of the Washed Up Emo podcast in 2019, looking back on the origins of that first 7-inch, “so let’s make something you can hold in your hand. It was a document.”

At the time, Dischord itself was just a vehicle for that document. But soon MacKaye and Jeff Nelson, drummer in both the Idles and a new band, Minor Threat, that the two had formed, noticed that a scene was growing around them. So they put out another document, a 7-inch by S.O.A., featuring their friend Henry Garfield, soon to be known as Black Flag frontman Henry Rollins, and suddenly the label was a going concern.

In the decades that followed, Dischord’s reach and renown would eclipse not just that of the band that launched it but that of almost any other independent record label in history. Its ethical dealings — no artist contracts, fixed album pricing printed on each release to ward off shady markups — became legendary. But even more so was the music. At first it was hardcore punk, as captured on early singles and the seminal Flex Your Head comp, but throughout the ‘80s the roster evolved at warp speed, inventing new forms of underground rock in real time. MacKaye moved on from Minor Threat to the more reflective and varied band Embrace and, later, the boundaryless sound world of the now-iconic Fugazi. Meanwhile, his peers took their own paths. Nelson, the label’s co-owner, focused on the more tuneful indie rock of Three and the High Back Chairs, while others, including future Fugazi members Guy Picciotto and Brendan Canty, unwittingly helped to write the blueprint for so-called emo with the cathartic, soul-baring Rites of Spring.

A whole generation of visionary post-hardcore followed, ranging from the arty (Shudder to Think, Nation of Ulysses) to the ferocious (Circus Lupus, Hoover) to the downright mystical (Lungfish). The label’s pace slowed somewhat around the turn of the century, with Fugazi going on hiatus in 2003 and archival releases becoming as common as new ones. But new acts, including the playfully bizarre dance-punk project Edie Sedgwick, nuanced art-pop outfit Beauty Pill, and subtle yet mighty two-pieces the Evens (MacKaye and drummer-vocalist Amy Farina) and French Toast (former Nation of Ulysses drummer James Canty and scene vet Jerry Busher, who had worked in bands including Allscars and the Spinanes) carried the torch. Recently a new wave of reunited acts and fresh collaborations — including Soul Side, Messthetics, Coriky and Hammered Hulls — have helped to make the roster sound as committed as ever. With close to 200 releases to its name (as well as many titles co-released with other labels), Dischord is both an invaluable archive, constantly growing via titles like this newly announced set of Minor Threat outtakes, and a story still being told.

Here are 20 titles that span the catalog, offered with the acknowledgement that dozens more entries would be needed to illustrate its full breadth.