Over recent years Addis has grown into a sprawling building site, where unfinished concrete skeletons, mirrored shopping malls, and tall metal cranes shoot up towards the sky; below, thousands of yellow taxis and Toyota mini buses hurtle along the knot of new roads, spurting out black smoke. But hidden among the shiny new buildings you can still catch a glimpse of Addis’ past: the cobbled streets that lead off Piazza, the old Italian roasting machines in Tomoca Coffee, and the typical azmari bets (“house of the musician”) where you can go and listen to traditional ethiopian folk music while sipping on a glass of tej, sweet fermented honey wine.

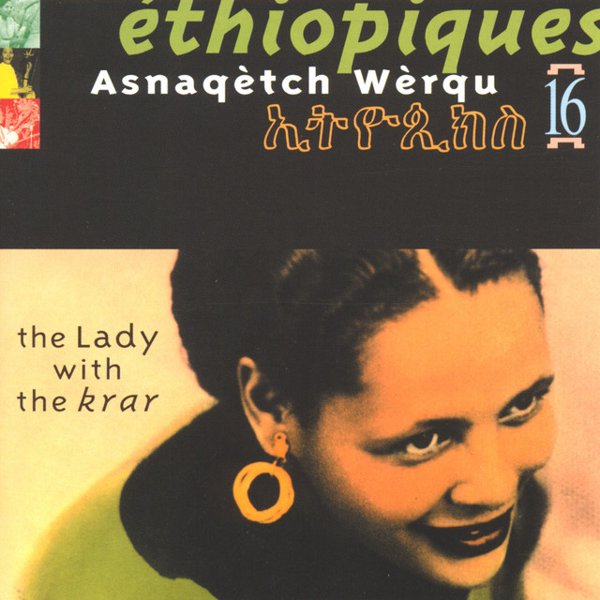

Azmari bets have been a feature of the city ever since it was founded in the late 1800s, and continue to be just as popular. The musicians here usually perform in traditional clothing, and play folkloric instruments such as the masenqo, a one stringed fiddle, and the krar, a stringed bowl-shaped lyre. It can get rowdy, as patrons are pulled up to dance eskista, the country’s beloved shoulder-jerking dance.

The popularity of traditional music isn’t surprising, as it still forms the basis of all Ethiopian popular music styles. Most modern genres in fact emerged from the meeting of these traditional standards and scales with the music and instrumentation of other cultures. In 1924, Prince Ras Tafari — who then went on to become Emperor Haile Selassie — visited Jerusalem, where he met a brass band of Armenian children orphaned by the genocide. He brought them back to Ethiopia, where, as the Royal Imperial Brass Band, they played important functions, and spawned the birth of several new orchestras, most of them government run.

By the late 1940s the most popular singers were accompanied by full brass bands who played traditional melodies on their new instruments. At the same time instruments such as the accordion and mandolin were making their way to Ethiopia through the Italian occupation, and Ethiopian musicians were adapting them to the traditional standards and pentatonic scales. Late musical legend Ayele Mamo for example played his Italian mandolin in the style of a krar, and had a defining role in shaping the sound of Ethiopian popular music of the 1950s.

It was in this period, under Selassie’s rule, that Ethiopian musicians began fusing western jazz with their own folk music, with intoxicating results. By playing the characteristic Ethiopian pentatonic scale on these louder, more powerful instruments, Ethiopian greats such as Mulatu Astatke created the soul-stirring new style known as Ethio Jazz. Although Astatke is widely recognized as the “founder” and main exponent of Ethio Jazz, there are hundreds of musicians who put their own spin on the style, adding doses of funk, soul, or even digging deeper into Ethiopian folklore for inspiration.

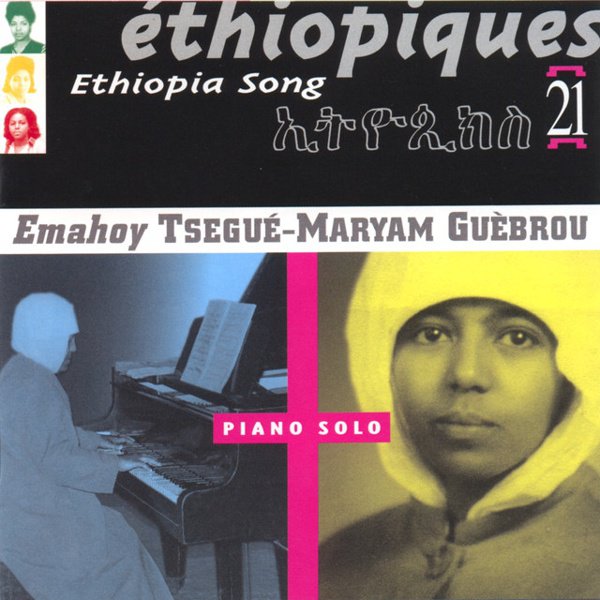

This period between the 1960s and 1970s is known as Ethiopia’s Golden Era, marked by a profound musical openness, experimentation, and prolific production. Its richness and idiosyncrasies are captured by Buda Musique’s excellent Éthiopiques series, curated by French musicologist and producer Francis Falceto, which brought Ethio Jazz to the world’s attention in the 1990s.

All of this vibrancy and musical production almost came to an end during Mengistu’s dictatorship between 1974 and 1991. The military Derg enforced nightly curfews, and all new music had to go through strict censors before being recorded. Still, Ethiopians did their best to find the way past the restrictions: the most popular clubs and hotel bars would simply lock up after curfew, and people had no choice but to party from dusk till dawn. Musicians also showed a renewed interest in the traditional poetic style sem-enna-werq (wax and gold), through which different meanings could be shrouded in seemingly innocuous love songs. Tlahoun Gessesse’s “Altchalkoum” (Can’t Stand Any More) is a great example of this, and was banned both by Selassie and Mengistu after him.

Although the Golden Era of Ethiopian music was relatively short lived, its impact and global popularity are enduring: Jim Jarmush chose Mulatu Astatke’s music to soundtrack his film “Broken Flowers,” Seifu Yohannes’ “Tezeta” was sampled by Common on The Game, and Italian guitarist Adriano Viterbini recently covered Emahoy Tsegue’-Maryam Guèbrou’s “The Homeless Wanderer,” to name but a few.

And while much has changed in Ethiopia, music still runs through the capital’s veins, in the raucous azmari bets and the city’s jazz houses, old and new.