Ska emerged in Jamaica in the late 1950s, as an organic outgrowth of the popularity of American rhythm and blues in a musical context that already included established local styles like calypso and the folk-derived indigenous music called mento. As all of these elements interacted and informed each other, a new genre developed, one that often drew on the swinging rhythms of jazz but was fundamentally characterized by a rhythmic structure that emphasized the backbeat: for every beat in a 4/4 measure, ska arrangements had the guitar and/or horns and/or keyboard putting a conspicuous stroke on the “and” of the count (one-and-two-and-three-and-four-and). Because the ear generally expects rhythmic accents and emphases to fall directly on the beat rather than after it, ska is built on rhythmic surprise and creates an almost irresistible impulse to dance. It became hugely popular quite quickly, and its popularity in both Jamaica and throughout the West Indian diaspora (especially in England’s Black urban enclaves) persisted into the 1960s before it was gradually displaced by the slower and more rhythmically elastic rock steady style, which itself was soon eclipsed by the even slower and smokier reggae grooves that were fully emergent by 1970.

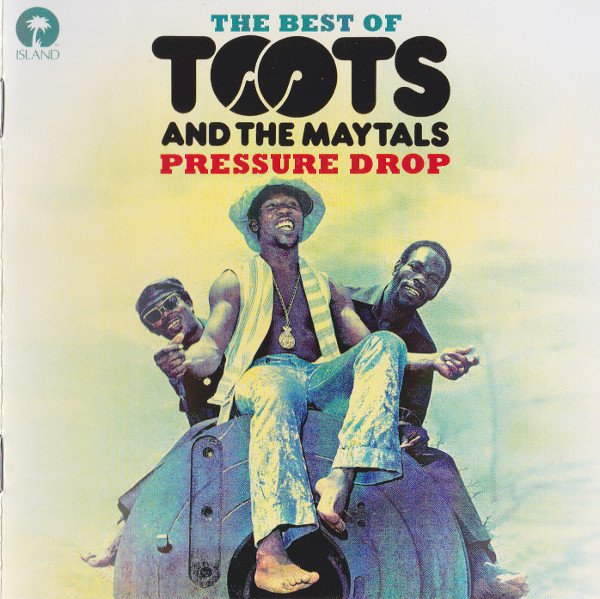

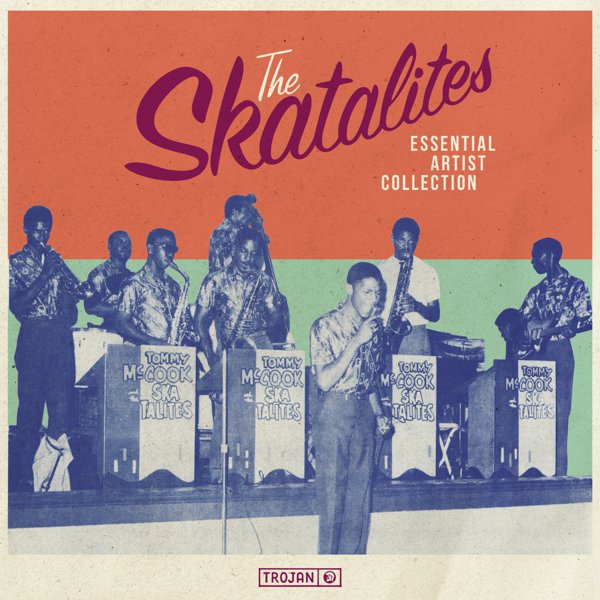

Ska lent itself nicely to both instrumental and vocal tunes. The earliest instrumental ensemble to gain broad popularity was the Skatalites, whose jazz-inflected compositions were hugely influential. Among early ska vocalists, Prince Buster and Desmond Dekker both remain legendary, but future reggae stars like Derrick Morgan, Justin Hinds, and Bob Marley all got their start as ska artists.

The contributions of producers to the development of ska is also important to note. Although many were notoriously unscrupulous in their dealings with artists, studio owners like Clement Dodd, Duke Reid, and future Jamaican Prime Minister Edward Seaga played an important role in giving talented musicians recording opportunities, public exposure, and distribution, and some (like Prince Buster) were musicians themselves as well as producers. Recordings that emerged during this period from studios like Federal and Studio One still influence the sound of contemporary reggae and dancehall music.

Although ska was fully eclipsed by rock steady and then reggae within a decade or so of its emergence, the style has experienced periodic revivals; the 2 Tone movement in England in the late 1970s was the first of these, and another occurred primarily in the United States in the early 1990s. While these ska revivals generally featured bands who combined the fundamental structures of ska with punk and rock elements, some artists worked explicitly to revive the original sounds of first-generation 1950s and 1960s ska – bands like Hepcat, the Stubborn All Stars, and the Toasters are examples of contemporary old-school ska revivalists.