In a career spanning only three decades, Frank Zappa wrote, performed and released music at a prodigious pace and has, to date, well over 100 releases under his name. He dabbled a little in both rock and jazz, and his bands often featured top-flight talent. But, as he’d be sure to tell you, he’d prefer to be remembered primarily as a composer: throughout his life his music featured nods to his classical idols (Stravinsky, Varese) and he wrote scores for groups like the London Symphony Orchestra, the Ensemble Modern and Pierre Boulez’s IRCAM.

Frank Zappa was born in 1940 in Baltimore, Maryland, but early in his childhood his family moved to southern California, where Zappa would remain for most of the rest of his life. As a teenager he drummed in local bands, but eventually switched to guitar. Simultaneously, Zappa soaked up music from sources as varied as Johnny “Guitar” Watson and Edgard Varese. After spending time as a freelance musician and working as a hired hand in Paul Buff’s studio in Cucamonga, Zappa opened his own studio and started pumping out music, only to be arrested in 1965 in a sting operation (he’d serve 10 days in jail). A tone was set: Zappa would work long hours in the studio splicing tape and tinkering with music, and he’d also cast a suspicious glance at authority figures.

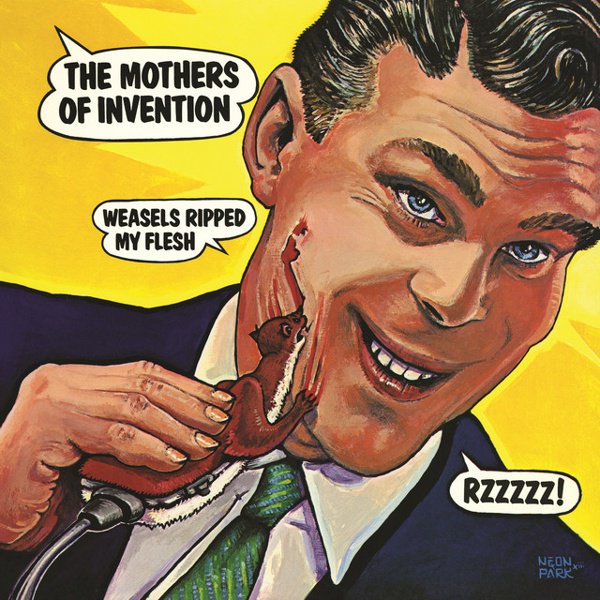

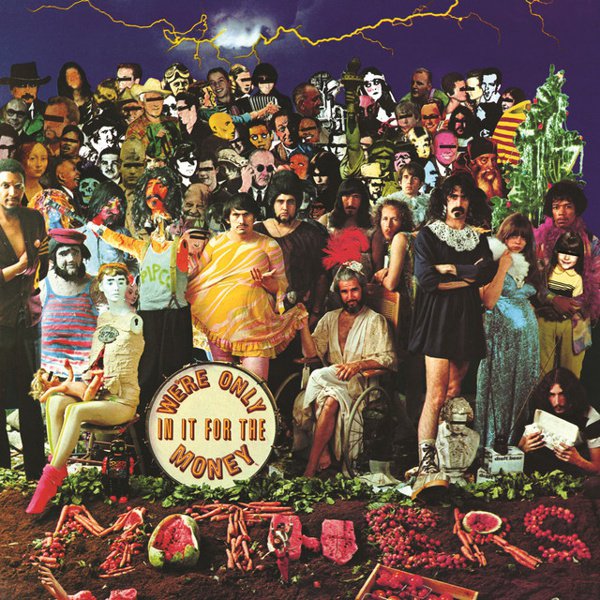

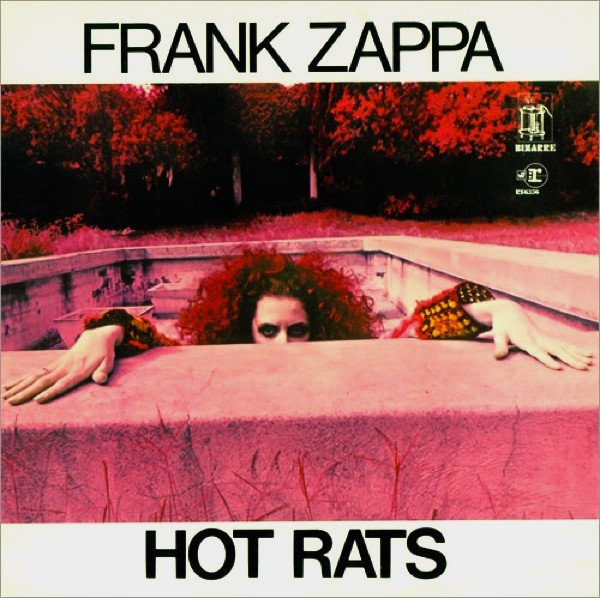

Zappa quickly rebounded, taking over a local group and re-christening them The Mothers. By the end of 1965, they’d relocated to Los Angeles and made a name for themselves, gigging around town at venues like the Whiskey-A-Go-Go. By year’s end, they’d signed on to Verve/MGM Records and in 1966, they released their debut: the double LP Freak Out!. The Mothers would spend the next few years working at a prodigious pace, releasing new records every year and spending a lot of time on the road. In 1969, Zappa broke up the band and released his solo record Hot Rats.

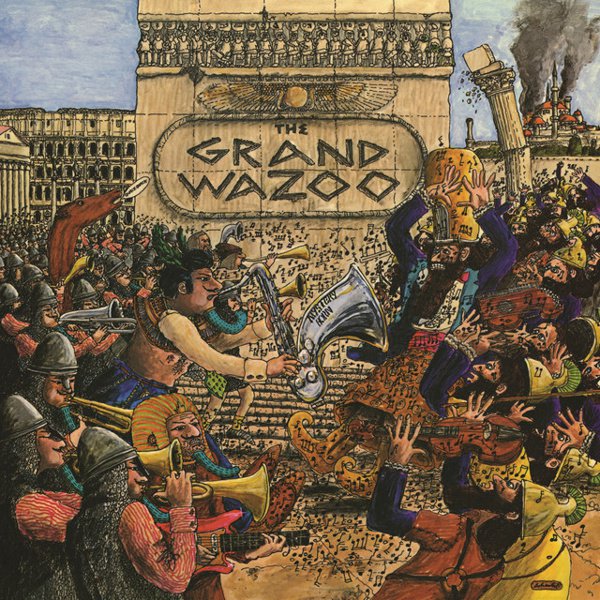

Throughout the early 70s, Zappa continued touring and recording. Even two accidents in late 1971 — first, a fire at a venue causing the loss of all his equipment, then an attack at a show in London that would crush his larynx and leave him in a wheelchair for months — didn’t slow him down. He worked with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra on 200 Motels, jammed with Yoko Ono and John Lennon at the Fillmore East and toured with a 20-piece big band. Eventually, he settled down with a smaller group featuring Ruth Underwood, George Duke, Chester Thompson and a few other musicians: this lineup would eventually be featured on over a dozen records.

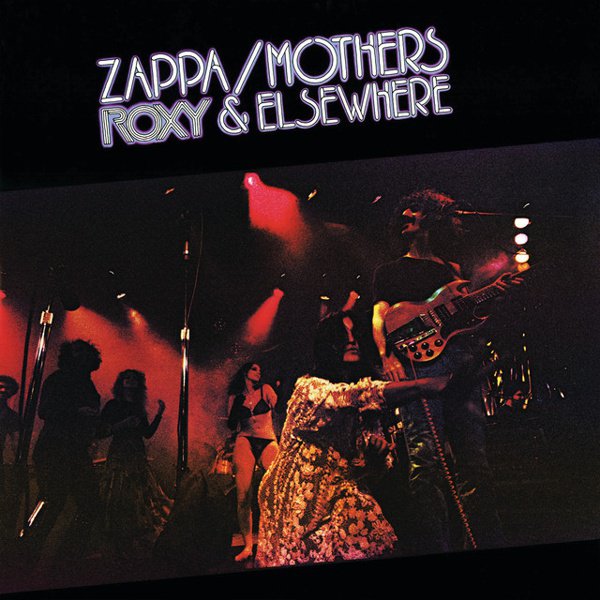

By the mid-70s, Zappa was regularly touring Europe and North America with ever-shifting bands, often completely retooling them for each tour. His music grew more complex and orchestrated, with songs opening up into vamps around which he’d play lengthy guitar solos. It also started taking more pointed shots at elements of society he disapproved of. Disco fans, gay culture, Republicans, born-again Christians or women’s liberation, few escaped his jibes. Even a nasty split with Warner Brothers did little to slow the pace of his records: he simply started releasing them though his own label.

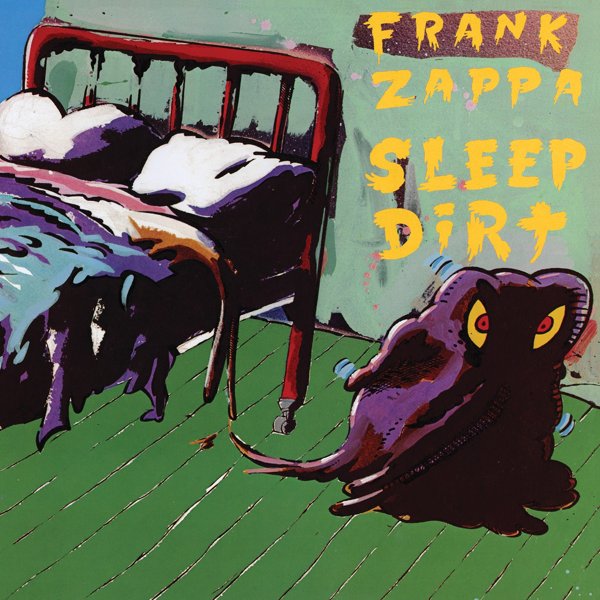

1983 marked the first time in almost two decades that Zappa didn’t tour. His interests had started to shift, and he began to write music for the London Symphony Orchestra, IRCAM and Kronos Quartet. He was also active politically, testifying to a Senate committee in 1985 about censorship and content warning labels on records. His final tour, in 1988, was an interesting mix of politically charged music — often taking potshots at televangelists and right-wing politicians — and horn-heavy new arrangements of older songs. However, the tour fell apart, with Zappa firing the band. He would never tour again, instead focusing his energy on writing scores, either for classical ensembles or for his Synclavier, and delving into his archives: the six-volume You Can’t Do This On Stage Anymore is a deep dive into his live performances over the past two decades. After a battle with prostate cancer, Zappa died in 1993.

Dying hasn’t slowed down the number of releases. In the almost 30 years since his passing, there’s been roughly one new Zappa release a year. Everything from Dance Me This’s avant-garde ballet to live concerts (Wazoo, Buffalo) to deluxe box sets has come out of his vaults in recent years. If nothing else, this steady stream shows how creative, hard-working and talented Zappa was during a relatively short professional career.