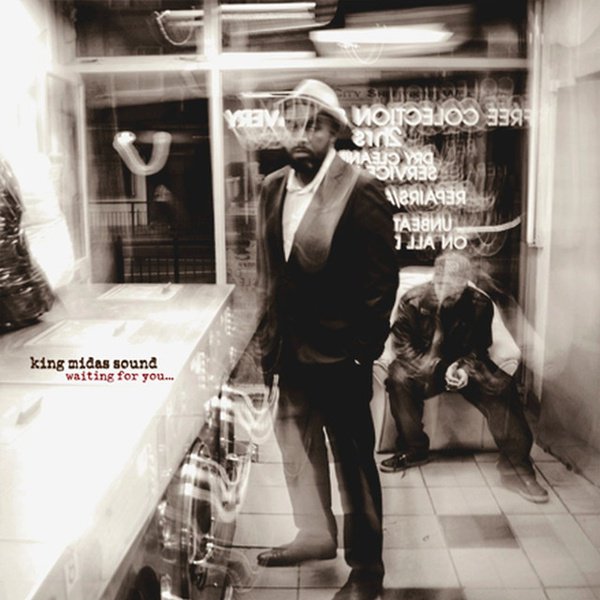

Hyperdub can’t claim sole responsibility for every major development in early 21st century dance music, but you wouldn’t be entirely wrong if they came to mind first. A generation after “Metal” Mike Saunders and Patti Smith made the rock-critic-to-punk musician jump, Glasgow-based musical theorist and UK dance fanatic Steve Goodman pulled off the post-rave equivalent, building off the cachet of his webzine to start a label of the same name. He’d helm the first two releases under the name Kode9 in 2004, singles featuring vocals credited initially to Daddi Gee and later retconned to reflect Gee’s more well-known alias The Spaceape. And the standard was set with the first entry in the Hyperdub catalog, that being the duo’s panic-pulsing, brink-of-annihilation uber-dub deconstruction of Prince’s “Sign o’ the Times” — which sounded like Linton Kwesi Johnson intoning apocalyptic poetry over a King Tubby transmission from the void — backed by a track called “Stalker” where the sprightly rhythms of 2-step were pushed into exclamatory, corroded-sounding blunt-force impacts and chemically washed in an intangible dread. It was a good way to pose the question: how harsh and spare and uncompromisingly dark can you make a record in the burgeoning post-2-step sound, and still give it the kind of essential pulse that keeps dancefloor dynamics exciting? If those early Kode9 + the Spaceape singles weren’t enough of an answer, Burial would provide the Q.E.D., striking with a devastatingly affecting yet rhythmically propulsive style that made him the first favorite dubstep artist of millions of listeners — many of whom couldn’t tell a Skream from a Benga.

While the label’s first few years felt autonomous to the point of near-insularity, that would change quickly. Sure, the core that carried the label for its first few years was so tight and so reliant on a handful of emerging artists — the aforementioned Burial and Kode9 + the Spaceape; grime-conversant crew L.V.; glitch-bass noisemakers Darkstar; the wonky mutations of Ikonika; Tokyo-based chiptune dubstepper Quarta330 — that the label’s fifth anniversary compilation 5 wound up bringing in label-unaffiliated peers like Flying Lotus, Martyn, and Joker to flesh it out. But that was a good omen, as it provided the kind of co-signs that broadcast the crucial idea that this wasn’t just a brand riding out dubstep’s grimy first wave. This was a label that not only had a future, but had a knack for introducing the future before most people knew it was arriving.

The shifts would come fast, but also wound up sticking — it’s not so much that Hyperdub went through flag-planting “phases” where certain genre trends held sway for a bit, but that they cultivated these ideas in ways that allowed them to grow and shift and hybridize while maintaining their essential character. If you hear a UK funky single on Hyperdub — a peak-era original like Funkystepz, or a next-gen adapter like Fiyahdred — then you can trust that the scene’s burn-bright-burn-fast moment of glowing hedonism was captured at its truest, when it was novel but not yet a novelty. If a Chicago footwork crew like Teklife gets brought on to the label and positioned at the peak of their genre, you can trust it’s legitimizing the original culture’s compatibility with the avant-garde, and not just trying to force it into that context. Hyperdub’s place in the pop pantheon is far closer to the underground than the populist, but it’s also a label run by a critic-slash-scholar-turned-artist who subsequently trusts the artists he signs to make the underground feel wide-open. It’s not that complicated, it’s just complex.

That integrity has left Hyperdub at the forefront of its realm no matter how dance trends ebb and flow — it’s an adaptability that’s comfortable with inspired genre hybrids, new as-yet-unnamed sounds, and throwbacks that tweak nostalgia more than they dwell in it. Well into the pandemic-damaged ’20s, when independent labels are at their most vulnerable, survival means being able to offer everything from pop’n’b conversants like Jessy Lanza to the essentially confrontational noise-house irreverence of 700 Bliss to the abstract yet intensely personal ruminations of Loraine James. Maybe you could still perch Hyperdub somewhere near the margins — a lot of the label’s finest work, past and present, could still be tagged as “experimental,” sure. But if some of it sounds a lot less experimental than it used to, that’s because many of these experiments were successful enough to permeate the mainstream.