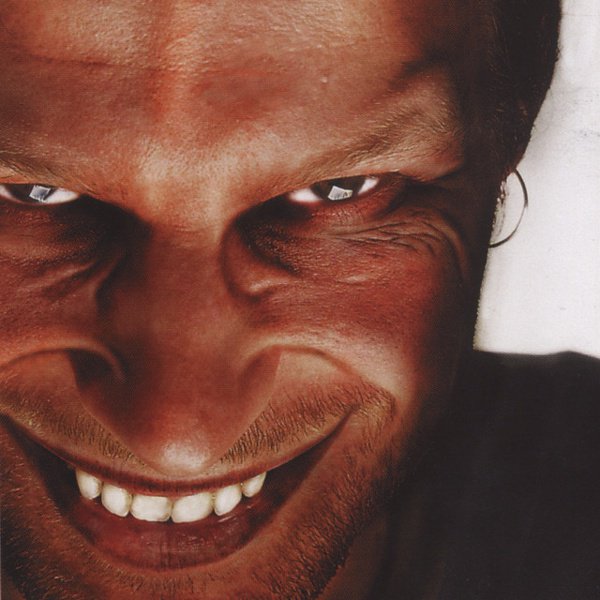

In the music business, racism does so much racism every day that you’d think it would be hard to pick a winner of Doing Big Racism. But you have found it—the most racist term in popular music. “Intelligent dance music” was a phrase invented to apply to early Nineties acts like Aphex Twin and the people who came immediately in his wake. Who Richard D. James was inspired by, though, were the acid house creators of Detroit and the junglists of London: Black and Latin folks who worked with a small clutch of white people. The world of IDM is the inverse. The bias is still so pervasive that I had to listen to three hours of IDM playlists on YouTube and Spotify before I hit a single artist of color. Was Dillinja not intelligent enough? Was Juan Atkins just a little dense? We know that nobody believed this, not even at the time of this term’s creation.

Somebody needs to recast IDM right away, maybe as “Frankstep” or “Orange Wave.” To their credit, almost all of the artists under the IDM umbrella mock the name, all for their own reasons. It’s important to remember, before we move on, that anything “unusual” done in the programming and filtering and structuring categories was done in these putatively unintelligent dance genres before any of these clowns rolled around. But a lot of these clowns are pretty great. So what is this stuff?

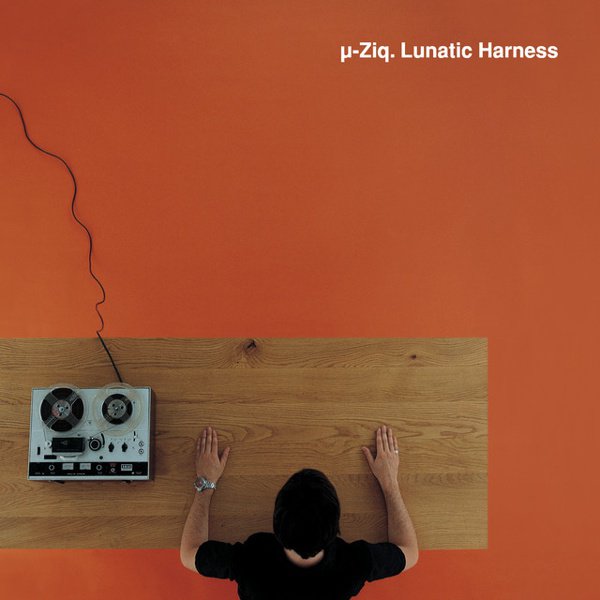

It really is “Aphex Twin and people who sound like him,” in short. What was happening, at the concrete musical level, was almost entirely the product of MIDI software; meaning that musicians were using bits of triggering software to make one machine manipulate the sounds on another, that latter machine usually a sampler or keyboard and the former a PC, usually not a Mac in the early UK scene. The piano roll interface of MIDI allowed the artist to make drums do things no human could do. That’s the first stylistic mark of IDM; the cascading, hyperspeed rhythms and gunfire pacing. What happened over time is fascinating, because the hardware changed significantly. Nowadays, anybody continuing in roughly the IDM vein is manipulating digital audio directly to get results reached in an entirely different way thirty years ago. If artists do still use MIDI, it could be convenience or a retro fixation—or maybe it’s for a musical reason after all. Tools do have their own character, and it’s hard to get the feeling of a Source Direct record without a cheap PC manipulating an Akai sampler. IDM music began as complexity rendered by primitive tools, machines that had never been designed for the uses they were put to.

The heart of the work comes from machines being pushed beyond their limits, and that was what Aphex Twin did from day one. Those trills that almost sound like a bird cooing? Maybe MIDI hammering, maybe a file chopped into lemon zest, who knows. But that sense of activity in “Flim” or “Peek 82454201” or “Nannou” is what gives this genre some actual personality of its own, not just negative affective affinity.

If we needed to go with a dumb genre name, “lifestep” would be closer to what goes on here. The first wave of fellas in here, all of them English, were taking the gear in front of them and wringing out a whole bag of glittering activity, much more visceral than intellectual. This is the formal manifestation of care and effort and enthusiasm, and that gave it some lasting power. Autechre braided everything back into itself, Squarepusher juiced up the already exuberant side of jazz fusion, Plaid turbocharged the idea of the pastoral, Prefuse 73 shredded hip-hop to make a hot salve, and Boards of Canada put their childhood science films into a taffy stretcher for everyone to see.

If you happen upon a really good IDM playlist, or god forbid make one, you get the impression of a sort of battery-operated lighthouse illuminating the world of late 20th century machines. The way Seefeel chopped up and recontextualized guitar rock was infinitely helpful, as it made it clear that the machine lovers were not necessarily against what had come before, but they absolutely wanted to complicate it and make the future stand on the same spot in the present as the past. And then hit play.

If you want to know how completely amorphous and nonsensical the term is, look at this entry from the fine folks at Masterclass. The bit that isn’t cribbed from the Wikipedia entry alleges that the “parent genre” of IDM is EDM, which is a funny thing to say since I did not hear the term EDM until well into the 21st century. I don’t just mean to clown on internet scammers like Masterclass, but to point out that this is a music that barely exists as a genre. It’s more like a cloud tag or a keyword that will sort of get you somewhere. It really just refers to early Warp acts, and that’s it.

After that, you’ve got artists like Prefuse 73 and Richard Devine and Sweet Trip who made great music in a related vein, but really do have their own thing. It seems most helpful to think of IDM as a little bit like metal, which, without a modifier, is almost useless, in that it apparently covers Metallica, Black Sabbath, and Deftones, three bands with almost no commonalities. IDM is more like a style sticker, or maybe a produce category like “Meyer lemons.” If you like lemons, sure, great, but you won’t know where they were grown or if they’re really Meyer lemons and it also won’t matter at all if it tastes good enough. You are not, unless you are insane, going to eat the lemon and then go back to the store to yell because you suspect it might not have been a real Meyer lemon.

Things get really odd if you chase IDM trails on Spotify or YouTube. You will find a range of things, much of which does not align with anything I’ve said here. It might mean nothing at all in 2022, or it’s like rockabilly or ska, a repertory genre where you simply reproduce the good stuff that’s been done. You should absolutely take the artists in this bucket seriously but you should be very skeptical of this genre name. To that end, we will end with a new synthetic definition.

Let’s start with what Discogs says: “IDM, or Intelligent Dance Music, is a style in electronic music emerging in the early 90’s and characterized by unusual, weird, distorted sounds, and drum lines consisting of very short bleeps and glitches. Originally applied to musicians like Future Sound Of London, Orbital, Aphex Twin, Black Dog and B12, the term is now extended to a multitude of artists…” Rate Your Music says: “Intelligent Dance Music, most commonly known as IDM, is a term invented in the early 1990s to describe the sound of a number of electronic musicians who sought to develop dance music beyond the clubs and more into the realm of home listening…Attempts have been made to alter the name of the genre and shake off the negative connotations, with Aphex Twin’s “braindance” description of his own music and Warp’s “electronic listening music” proving somewhat popular.” So there is a sort of soft consensus here. The rhythms were divorced from dancefloor functionality—they got chopped up, softened, and sprinkled amongst other elements. The textures went sad, maybe even sadboi. This posits IDM as a precursor to the lo-fi study beats movement. What happened to these rhythms is more interesting through the lens of gender than race, ultimately. The stay-at-home cyclotron of IDM was able to feminize beats, or at least open them up to femme energy. One of the artists tagged most often as IDM is Bjork, who stopped singing with traditional bands the moment she left the Sugarcubes. IDM is the precursor to both hyper-pop and the bedroom chill culture. People wanted to use rhythm and synth sounds but not for the dancefloor, and this began a whole family of music that has no real precedent in rock and roll or any other kind of bandstand or proscenium stage music, DJing included. IDM was ultimately the beginning of a whole new home recording revolution. Homewave? Homecore? Is that what it really is? Music that began with lots of people moving in public to one person at home, not moving.