The classical music of India sounds very different from that of Europe, which is what most Western listeners imagine when they hear the word “classical.” Whereas Western classical music is traditionally all written out ahead of time, with very little room for improvisation, in Indian music a performance is typically based on a fixed melodic framework called a raga, which is governed rhythmically by a tala. Within the structure of the raga and the tala, the instrumentalist improvises both melodically and rhythmically; the improvisation itself represents the substance of the performance. In this sense Indian classical music is more closely related to American jazz, and as in the case of jazz, the quality of a performance is judged significantly by the musician’s skill at responding creatively to the music while working within the rules of the melodic and rhythmic structure.

Another significant difference between Western classical music and that of India is that whereas Western classical music (especially prior to the 20th century) focuses strongly on harmonic development, while leaving melody relatively simple and rhythm very simple indeed, Indian classical music foregoes harmonic development entirely, while developing both melody and rhythm to a very high degree of sophistication. To Western ears attuned to melodies constructed from the diatonic scale, with occasional excursions into the chromatic, the microtonal ornaments and melismas of Indian classical improvisation may not even sound like melody at all; and to those used to counting in 4/4, 3/4, and 6/8 time, it can seem impossible to keep track of the long and complicated rhythmic cycles of a tala.

It is worth noting that each raga is written with an emotional purpose in mind: particular ragas are intended to be performed at specific times of day or year, and are intended to evoke specific moods. An Indian musician can sometimes court controversy, for example, by playing a morning raga during an afternoon or evening performance. Audiences tend to be well educated and knowledgeable, and concert listeners can often be seen marking the beats of a tala by quietly tapping different fingers together or turning their hands up and down along with the rhythm. During a concert, the audience may react with applause to particularly exciting or skillful passages of interpretation.

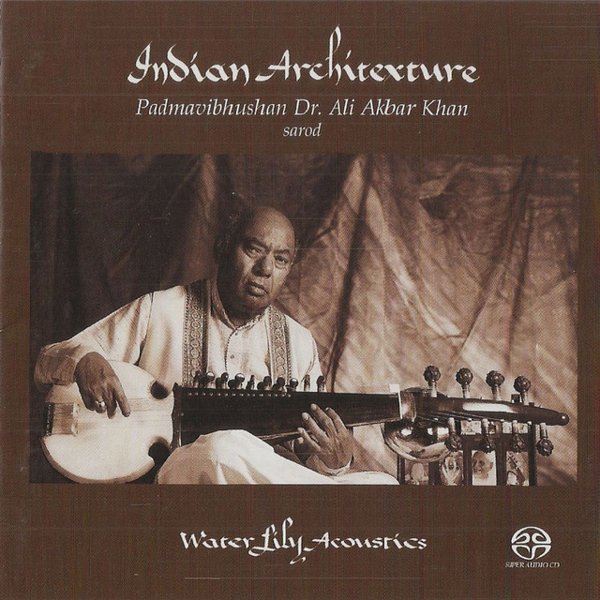

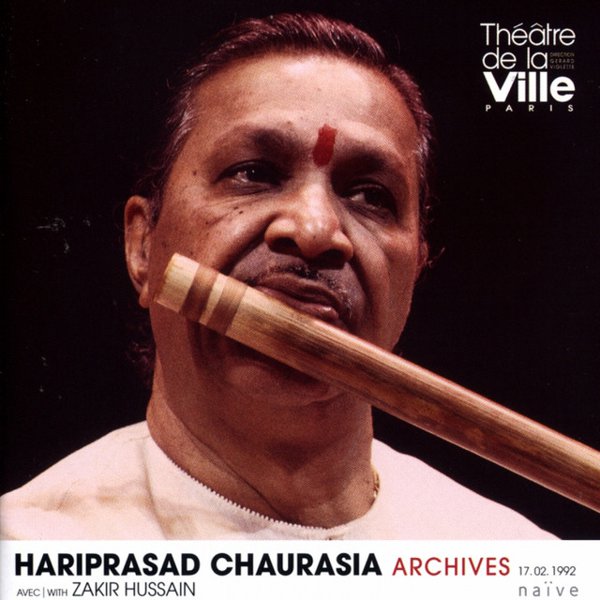

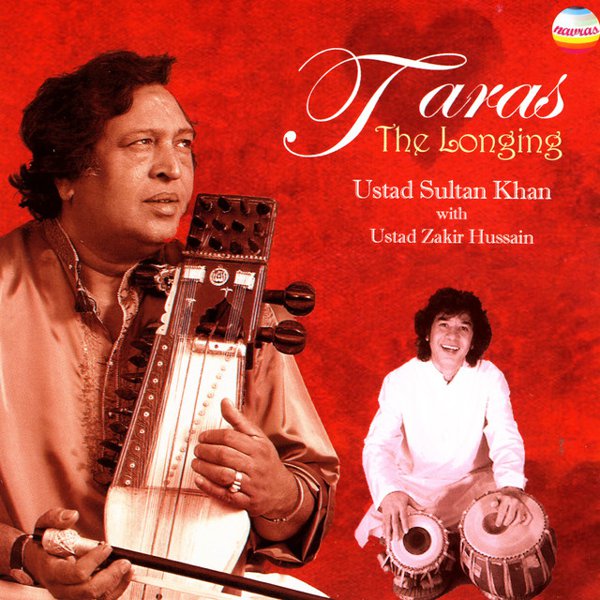

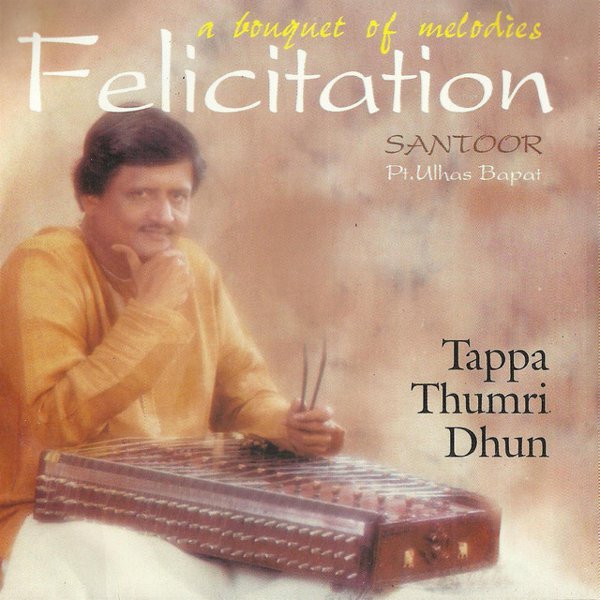

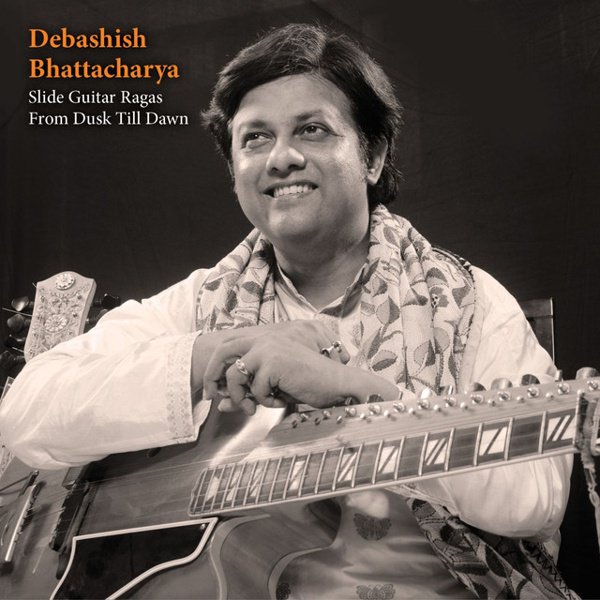

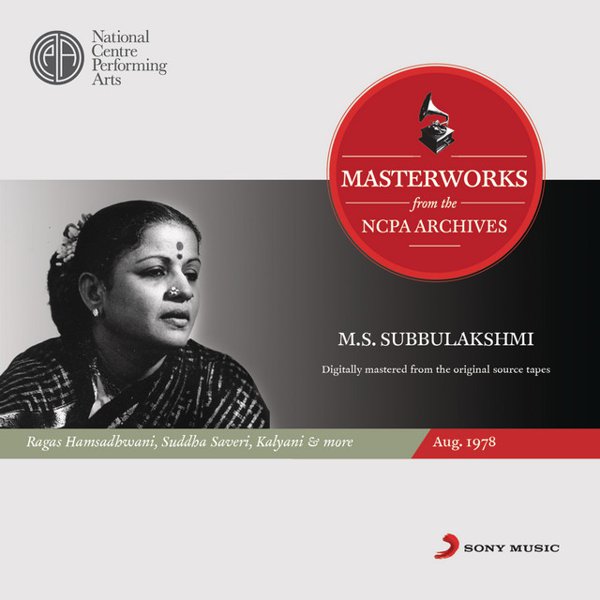

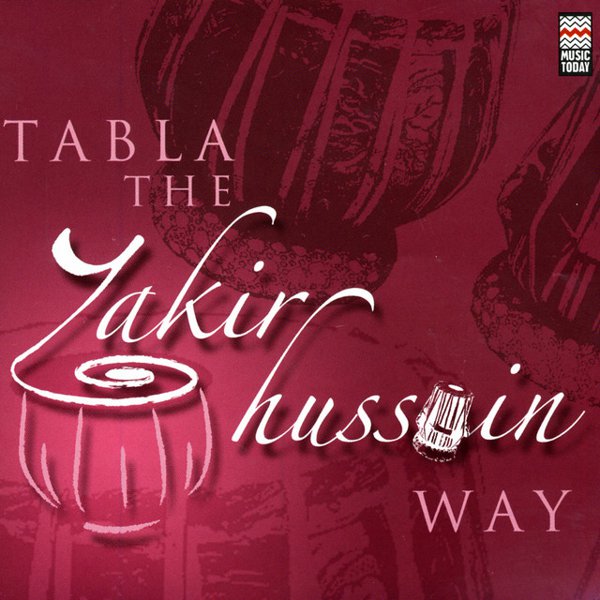

There are two main schools of Indian classical music: that of the North (Hindustani) and that of the South (Carnatic). The differences between them may not be immediately apparent to the casual listener, but are still quite significant. For example, there tends to be more rhythmic intensity in Carnatic music, and more of the music in a performance will have been composed ahead of time rather than improvised on the spot. Hindustani music can itself be subdivided into two broad subgenres, khayal and dhrupad; the former is a more modern form and the latter much more ancient. The Hindustani and Carnatic styles have somewhat distinct instrumental traditions: you are more likely to hear the sitar, the bansuri, the shehnai, and the tabla in Hindustani music, while Carnatic musicians favor such instruments as the veena, the mridingam, the venu, and the gottuvadyam. Singing is much more common in Carnatic than in Hindustani music.

To those approaching it for the first time, the classical music of India may seem dauntingly complex and foreign. But, just as with all other musical traditions, it’s completely possible to enjoy it without fully understanding it; the structure and rules of the music create patterns that anyone can simply relax and enjoy. And the richness and complexity of this music mean that one can always learn a little more about it, and thereby gain even more pleasure from it.